Italy discovers intimacy behind bars The first “intimacy rooms” are opening in Italian prisons, where inmates can meet their partners without supervision

In recent months, some Italian prisons have begun opening their first intimacy rooms, small spaces furnished with a bed and a bathroom, designed so that inmates can meet their partners without constant surveillance. It’s a major change, not only logistical but cultural, in a prison system that for decades has excluded emotional and sexual expression as part of human life. According to the Ministry of Justice, out of 189 penal institutions, 32 have declared that they have suitable facilities, while the remaining 157 do not. However, data from the association Antigone suggests otherwise: currently, there are only five or six operational rooms: in Terni, Parma, Padua, Trani, and, as of November 1st, also in the Lorusso e Cutugno prison in Turin.

The turning point: Constitutional Court ruling

The possibility of creating spaces for emotional and sexual expression in prisons comes from a 2024 Constitutional Court ruling, which declared the absolute ban on sexual and emotional relationships in prison unconstitutional. The Court recognized that “affective and sexual life falls within the inalienable rights of the person” and that punishment, as stated in the Italian Constitution, must aim at rehabilitation, not be punitive or degrading. Following the decision, the Department of Penitentiary Administration (DAP) issued guidelines to regulate these meetings: once a month, in private rooms under external supervision. The rooms cannot be locked from the inside and must be inspected by a prison officer before and after use. Excluded are inmates under 41-bis and 14-bis regimes, those in medical isolation, or those who committed disciplinary violations in the previous six months.

First Experiences and Resistance

The first such space was inaugurated in the Terni prison, after two inmates received authorization from the surveillance court. From there, the initiative gradually spread to Parma, Padua, and Trani, reaching Turin, where the new room was set up in the “Rainbow Pavilion,” dedicated to semi-free inmates or those with work permits outside the facility. Associations that have long fought for prisoners’ rights describe this as “a step toward civilization.” Yet concerns remain. The Osapp prison police union criticized the decision to entrust the management of these rooms to prison staff, calling instead for the introduction of specific permits for intimate visits. Even Monica Formaiano, the prisoners’ ombudsperson for Piedmont, while acknowledging the measure’s importance, warned that it could increase the workload for officers.

Affection as Care

For those living and working behind prison walls, this change is above all symbolic. It’s not seen as a matter of sex, but of human dignity, a right that should never become a privilege. Numerous studies confirm that inmates who maintain emotional relationships during detention exhibit fewer violent behaviors, suffer less from isolation, and are less likely to reoffend after release. In this sense, the opportunity to experience intimacy in prison is not an “emotional bonus,” but part of the process of rehabilitation and social reintegration.

A two-speed Italy

Despite the push from the Constitutional Court and the support of human rights organizations, the spread of intimacy rooms in Italian prisons is slow. Many institutions lack suitable spaces or prefer to wait for a formal court order before complying. The result is a patchwork Italy, where the right to intimacy depends not on the law, but on one’s postal code. In France, Germany, and the Netherlands, private visits are a consolidated practice, considered part of the rehabilitative path. Italy, as often happens, arrives late.

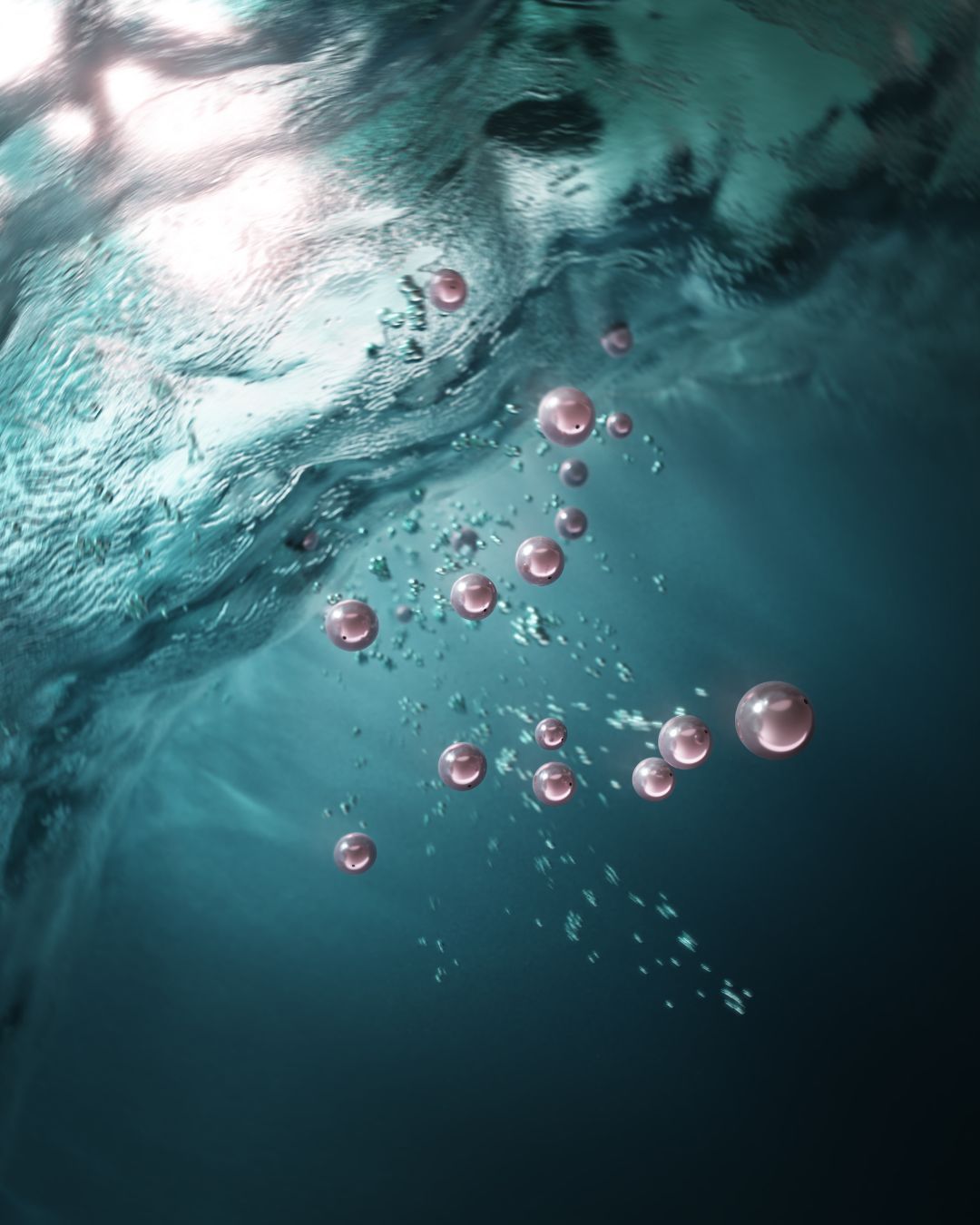

A fragile but necessary right

The so-called “love rooms” are not just a symbol, but a testing ground to measure how willing the country is to recognize the complexity of human nature, even behind bars. Because recognizing the right to affection does not mean indulgence, it means giving meaning back to punishment. As the Constitutional Court reminded us, “dignity is not suspended by imprisonment.” And perhaps from these small spaces, locked from the outside but finally open to life, a little fresh air may begin to flow into Italian prisons.