Regencycore 2026: the past that never passes From Netflix ballrooms to gothic moors: anatomy of an aesthetic that reinvents history

Every time Bridgerton reappears on the Netflix screen, with the punctuality of a social season and the same ability to monopolize conversations, fashion loses all composure and reacts like a romantic heart faced with a letter sealed in wax: it quickens, sighs, and surrenders with elegance. The new season only confirms the ritual. We long for fabrics that rustle like restrained confessions, volumes that occupy emotional space before physical space, silhouettes designed to be looked at and, above all, remembered. The Regency elegance, filtered through the spectacular lens of the series, does not aspire to historical reconstruction but to sensory intensity. This had been clear from the very beginning, as Ellen Mirojnick, costume designer of the first season, explained: start from history and then betray it gracefully. In 2026 this mechanism tightens, refines, darkens. Aided by the gothic-pop imagery of Wuthering Heights directed by Emerald Fennell, nostalgia takes on shadows and sentimentality becomes highly shareable. Visual romanticism stops being a decorative interlude between two minimalist seasons and becomes dense, restless, fully aware of its own theatricality. Thus the new Regencycore takes shape, a shared aesthetic grammar, deliberately scenographic.

What Regencycore really is (and why we’re so obsessed with it)

Regencycore formally emerges as a reinterpretation of English fashion between 1811 and 1820, the period during which the future George IV ruled as Prince Regent. Culturally, however, it extends far beyond the official dates and spills into the 19th-century romantic imagination. Think of the literary world of Jane Austen, made of candlelit balls, witty conversations, emotions compressed beneath the surface of good manners, and empire-style dresses. Its aesthetic grammar is immediately recognizable but, above all, emotionally legible: a mix of empire silhouettes, puff sleeves, expressive corsets, architectural bows, opulent jewelry, pastel palettes, and emotional drapery. But be careful. Its contemporary incarnation is not sartorial archaeology. It is cinema, it is fantasy. Visual storytelling applied to the body. In 2026 Regencycore is a child of widespread visual culture: streaming, social media, red carpets, music videos, TV series, photography, editorials. It’s not about dressing like then, but about evoking a scenographic romanticism that is immediately recognizable and perfectly compatible with the feed. It isn’t nostalgia. It’s a cultural reflection. A kind of shared desire for narrative beauty and aesthetic intensity.

The long flirt between fashion and the 19th century

Long before the term Regencycore entered the cultural vocabulary, fashion had already established an extraordinarily fertile relationship with the Regency aesthetic. After all, the 19th century is an inexhaustible mine of forms, tensions, and symbols. The most controversial? The corset. Born as a tool of social discipline, a device for controlling the body and a visible sign of hierarchy, it never truly disappeared. It has been reinterpreted, liberated, transformed into architectural structure, aesthetic statement, and even emancipation. Designers such as Vivienne Westwood and Jean Paul Gaultier turned it into a permanent creative language, capable of oscillating between rebellion and theatricality. At the same time, the empire silhouette, high under the bust, fluid, surprisingly modern in its freedom, has been reinterpreted in a contemporary key by maisons such as Valentino and Givenchy, demonstrating how freedom of movement can often be more seductive than structural rigidity. Fashion never copies history. It absorbs it, transforms it, metabolizes it until it becomes emotionally contemporary.

Regencycore on the 2026 runways

The Spring/Summer 2026 runways have metabolized the Regency era, transforming it into a constructive principle. At Christian Dior, under the direction of Jonathan Anderson, volume becomes emotional architecture made of organza, petals, and sculptural constructions. Meanwhile Giambattista Valli and Simone Rocha dress modern debutantes in organza and crinolines—romantic, yes, but with a subtle sense of unease. Palettes are delicate, from powder pink to white, also for the porcelain-doll creations of Yuhan Wang. Erdem Moralıoğlu draws inspiration from the French medium Hélène Smith and works through narrative layering. The result? Fabrics that seem to hold memory, antique lace, hourglass mini-dresses, floral motifs, and corsets that appear to have stepped out of a gothic novel still being written. Others push further toward dystopian fairy tales, such as Pauline Dujancourt and Dilara Findikoglu. Elsewhere, for example at Balenciaga, the construction of the body becomes an exercise in controlled tension. Max Mara reinterprets rococo opulence through the figure of Madame de Pompadour, transforming decoration into contemporary structure. Saint Laurent, led by Anthony Vaccarello, amplifies drama through chromatically assertive volumes and bows. Acne Studios deconstructs the corset for everyday wear, while Prada reinterprets ceremonial accessories, such as opera gloves, on rigorously contemporary silhouettes. Meanwhile, the volumetric romanticism cultivated for years by Cecilie Bahnsen and Molly Goddard continues to expand as a shared language.

Dark Regency: the meeting of Regencycore and gothic romanticism

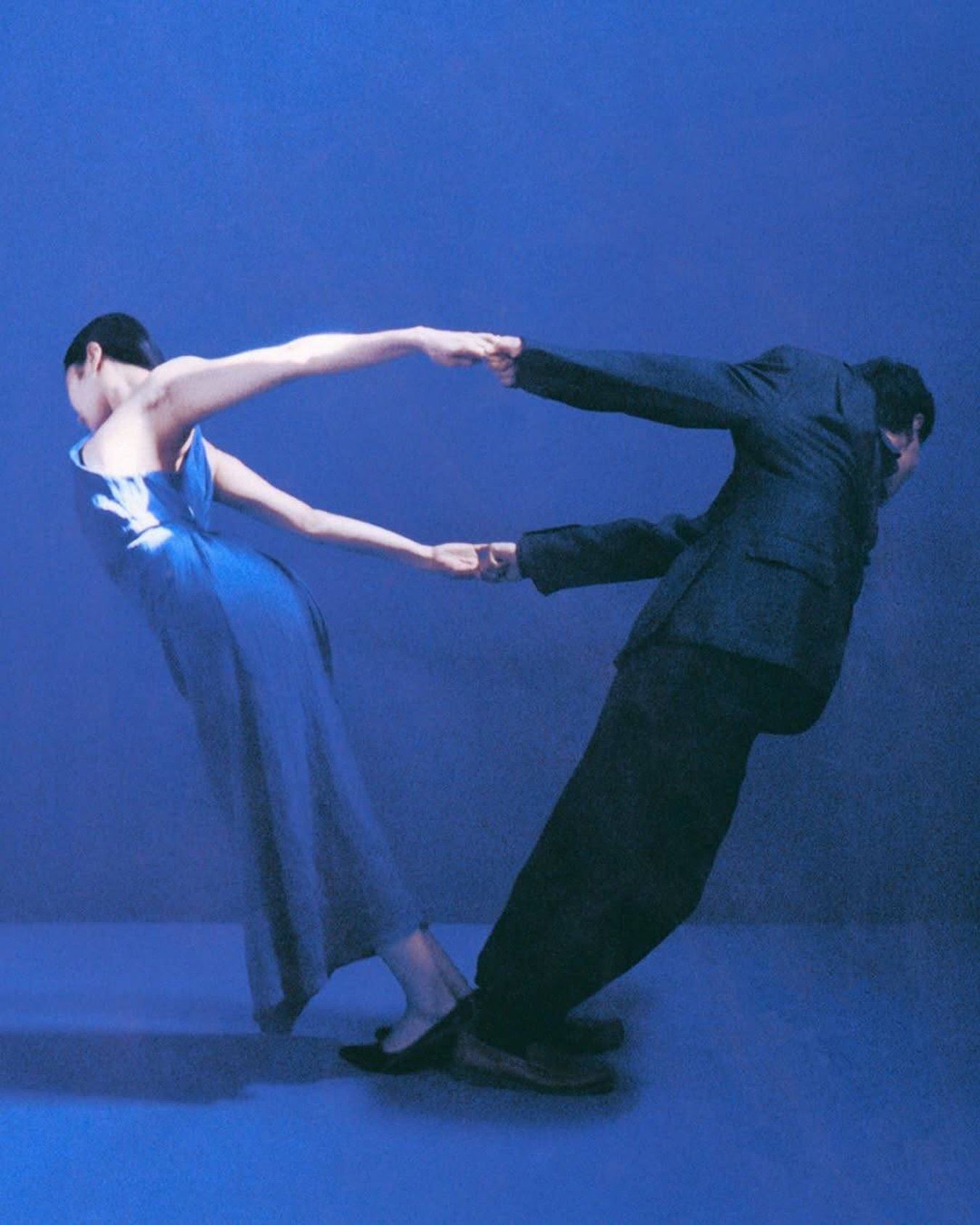

If television series reignited the passion for aristocratic opulence, cinema added shadow, torment, and darker emotional matter. The adaptation of Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë, directed by Emerald Fennell and starring Margot Robbie, emotionally reinvents historical eras. Costumes by Jacqueline Durran deliberately reject philological precision. They do not seek to place the story in time, but to make it sensory. Elizabethan, Georgian, Victorian, painterly suggestions, memories of 20th-century cinema, and even contemporary elements coexist in an aesthetic that could be defined as psychological. Every garment becomes a wearable state of mind. Inevitably, the clash between Bridgerton-style fairy-tale aesthetics and Brontëan gothic romanticism has created the Dark Regency, a new ideal of a romantic wardrobe that adds to aristocratic sugar-spun elegance a strong dose of tension, unease, and restrained desire. The Dark Regency is the aesthetic response to an era that seeks visual intensity but also feels nostalgia for something that never truly existed, yet that we stubbornly want to experience, at least through what we wear. Much to the dismay of fashion history purists.

Romanticism as a global cultural language

The new Regencycore no longer belongs only to fashion. It has become a widespread sensibility. The most extreme example is the looks worn by Margot Robbie during the promotional tour of Wuthering Heights. For her, stylist Andrew Mukamal created a visual saga made of sculptural corsets, couture, theatrical velvets, and details that seem to come from a fever dream and drive the internet wild. How to translate this hybrid trend, hinting at the British Regency while expanding to include every element with a romantic, old-world echo, is demonstrated by Charlie XCX and Rosalía, who play with ribbons, organza, bows, and aristocratic theatricality. The lesson? The ideal wardrobe does not function as historical costume, but as a wearable symbolic system. Wide princess skirts coexist with everyday pieces, monumental bows take on architectural value, oversized jewelry acts as visual statements of presence, and palettes of mint green, baby blue, and antique pink shape mood before color. Fabrics flow, fold, and drape as if they possessed an emotional life of their own. Mini bags inspired by historical reticules return reinvented, while gloves, masks, and ceremonial details suggest theatricality more than functionality. Perhaps it is the emotional response to a present perceived as too functional, too pragmatic, too disenchanted. After years of minimalism, desire becomes visible again. Tangible. Ornate. Between imaginary ballrooms and storm-swept moors, fashion has found its new unstable balance: romanticism and unease, history and invention, lightness and drama. In other words, the past never truly returns. But sometimes it decides to dress better than we do.