Welcome to the era of character dressing Notes on ready-to-wear identity. In other words, tell me who you play and I'll tell you who you are

Getting dressed, ultimately, has never been a neutral act. Even when we pretended it was, even when we reduced it to a matter of practicality or good taste, clothing has always functioned as a silent statement. For as long as we can remember, we’ve chosen what to wear to express who we are, who we’re trying to become, or, more secretly, who we wish we were. It’s a language, a system of signs that speaks before we ever open our mouths. Through clothes, we’ve told stories about our tastes, our obsessions, our reading lists, the films that changed our lives, the artists who shaped how we exist in the world and made us feel less alone. From punks to mods, from grunge kids to ravers, from goths to early indie sleaze, getting dressed was long an act of mutual recognition, a way to belong. It wasn’t just about aesthetics, but about values, political stances, and worldviews. An outfit was a complex, layered sentence, often imperfect, but sincere. Today, however, something seems to have shifted. The narrative depth of clothing appears to be thinning, replaced by a constant performance, by an aesthetic that exists primarily to be seen, shared, and validated. It’s within this short circuit between storytelling and surface, between belonging and visibility, that contemporary character dressing takes shape.

Identity as a role: from construction to casting

Character dressing means dressing like a character one imagines, desires, or aspires to be. In itself, this is nothing new, we’ve always used clothes to experiment with alternative versions of ourselves. What’s different today is how these characters are built. Where they once emerged from an inner world shaped by cultural references, lived experiences, and real communities, they now often seem constructed from the outside in, like ready-made masks. Identity becomes prêt-à-porter not just because it’s wearable, but because it’s easily replaceable. One character a day, an aesthetic on rotation, a moodboard that shifts with the algorithm. The wardrobe turns into an archive of masks rather than a collection of lived stories. Multiplicity itself isn’t the issue—it has always been a strength, but rather the lack of rootedness. When every character is interchangeable, none of them leaves a trace.

From method dressing to character dressing

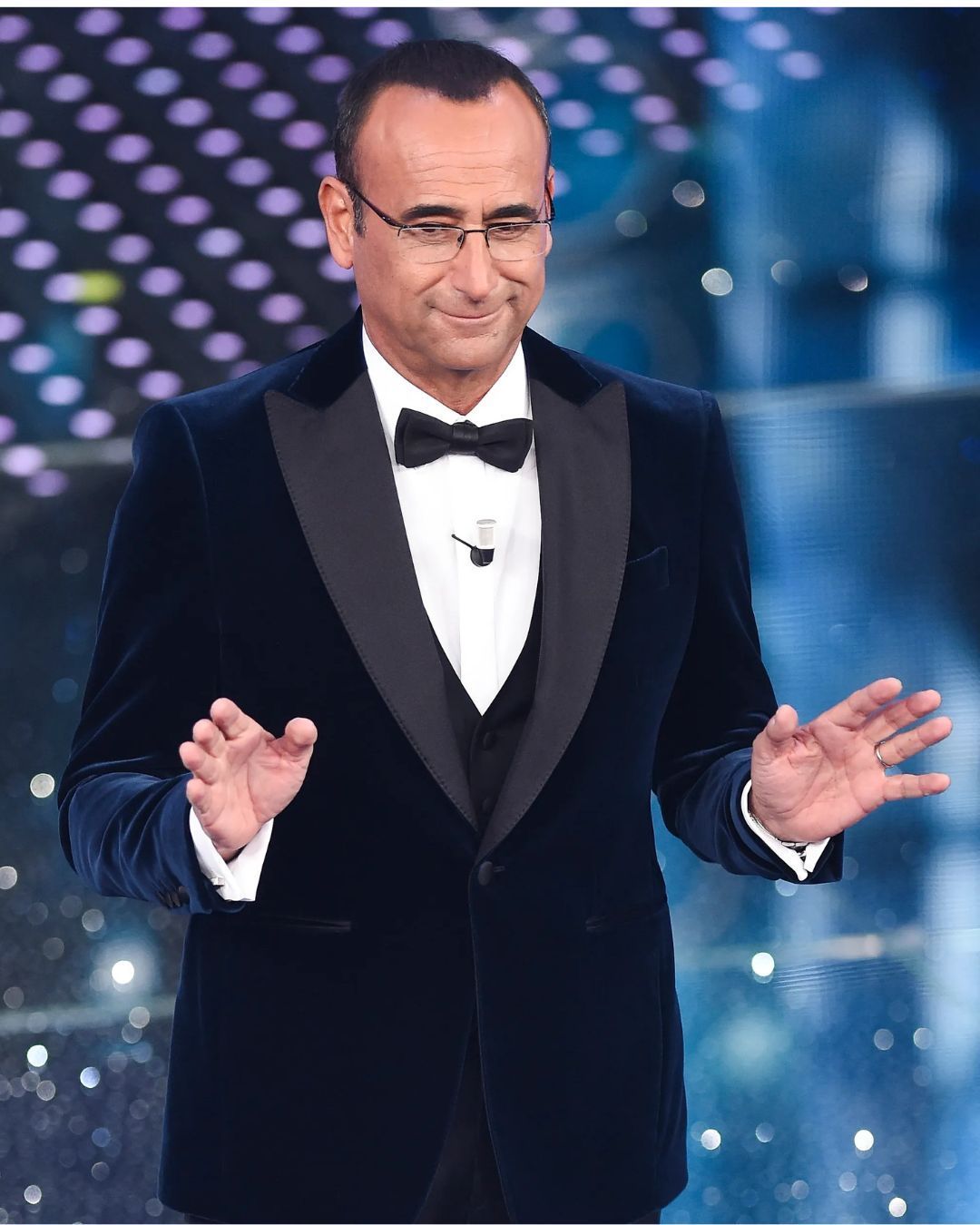

The red carpet has played a crucial role in this shift. Method dressing -the practice of dressing in continuity with a character played on screen, even during promotional tours - has gradually transformed into a hyper-aware communication tool, a marketing lever, a meme generator, content designed to live longer on TikTok and Instagram than the work itself. From Margot Robbie to Zendaya, all the way to Timothée Chalamet, the outfit no longer accompanies the narrative, it often anticipates it, replaces it, amplifies it until the story itself becomes secondary. Once internalized, this logic has filtered into everyday life, producing a clear side effect: we start dressing as if we’re always in promotion mode. Promoting ourselves, our image, our brand identity. Character dressing fits perfectly into this mechanism, where a character doesn’t need to be true, it just needs to be effective. The problem is that when everything is built to work at a glance, to be decoded instantly, complexity becomes an obstacle.

Uniforms without communities

In an era where identities are fragmented, fluid, and often overloaded, fashion responds with a return to uniforms. Sailorcore, military jackets, utilitarian codes, symbolic armor. Dressing as part of a group - real or imagined - reveals a deep need for structure and belonging. But there’s a crucial difference between wearing a code because you live it and wearing it because you recognize it. Once, dressing punk implied taking a stance, accepting social risk, choosing a side. Today, it’s often enough to know the aesthetic. Contemporary character dressing produces subcultures without communities. The signs are correct, the references recognizable, but the friction is missing. There’s no conflict, no duration, no emotional investment. The uniform becomes a visual shell that promises simulated belonging: reassuring, easily switched off. It doesn’t unite; it decorates.

Fashion and Gen Z: archetypes everywhere, meaning fading

Recent fashion weeks feel like massive open castings full of characters. (Remember Demna’s first collection as Gucci’s new creative director?) Dior and McQueen’s piratecore, Erdem’s rococo, the sailorcore of Duran Lantink x Jean Paul Gaultier, Ann Demeulemeester’s Napoleonic style, and Miu Miu’s reimagined tradwife aesthetic are powerful archetypes, heavy with history, yet at risk of becoming mere costumes when disconnected from real experience. The issue isn’t playing with codes, but doing so without questioning what we’re actually communicating. In this version, character dressing becomes a sequence of masks that leave no memory. Gen Z, immersed in a constant flow of images, references, and micro-aesthetics, has internalized this logic better than anyone else. Its visual language is fast, ironic, layered, deliberately loud, nostalgic, and deeply rooted in online culture. The risk? Turning identity into a performative loop, endlessly updateable, permanently provisional. In generational character dressing, the outfit is often designed to function primarily within the two-dimensional space of the screen.

Getting dressed to say something again

Maybe 2026 will be the year of the switch. We’ll reach a point of saturation where performative aesthetics lose their appeal and the desire for meaning returns. Enough with character dressing as superficial escapism. We’ll stop asking whether an outfit is Instagrammable and start asking whether it’s meaningful, whether it truly says something about us, our obsessions, our cultural references, our way of being in the world. Because getting dressed, in the end, has always meant finding a visible way to express something invisible. And perhaps, in a world that’s constantly performing, true radicality will lie in wearing clothes that don’t just seek attention or immediate approval, but say something real.