The paradox of clean grunge makeup From Seattle rain to TikTok feeds

Kurt Cobain saved my life. Not in a motivational-poster kind of way, not out of nostalgia reconstructed after the fact. I went through high school inside a Nirvana t-shirt, worn out and stubborn, carried like a second skin. Over frayed jeans, with battered All Stars and a flannel shirt tied around my waist. It wasn’t a shirt pulled absentmindedly from the shelf of a low-cost chain, chosen because it “went with everything” or because it suddenly came back in style thanks to an algorithm. No, wearing it meant taking a stand. It was a clear declaration of refusing to belong to the conformism of my classmates. It screamed to the world that I didn’t want to fit in, that I belonged to another tribe. That t-shirt was at once a political and aesthetic manifesto, but also, perhaps, a desperate act of love. A love screamed at the top of my lungs for Nirvana, Alice in Chains, Soundgarden, Pearl Jam, Temple of the Dog, and all those voices that, in the ’90s, seemed to understand better than anyone else the chaos boiling inside me.

Does clean grunge makeup make sense?

Many years have passed since then, and yet that emotional thread has never really broken. When I see a teenage girl wearing the same shirt that marked the first scars of my growth, I catch myself feeling proud, as if an underground legacy had reached her. But the feeling evaporates in a flash when I realize that, for her, Nirvana are nothing more than an old name, a band with “the dead singer” and little else. Worse still when I discover that the very aesthetic that was once born as a visceral, furious rejection is now being scrubbed clean and packaged under a label that sounds like blasphemy: clean grunge make-up. A formula that pretends to tame the iconography of disorder, sterilizing it into a polished aesthetic that has nothing to do with swollen under-eyes after a sleepless night, smudged lips from a drunken kiss, or eyeliner melting during a concert.

Grunge was never clean

Real grunge was never meant to please. It was born out of Seattle’s damp cold, from threadbare hoodies found in thrift stores, from sweaters worn out of necessity more than style. Michael Lavine, photographer and friend of Nirvana, says it clearly: people had no money, they dressed like that to protect themselves. And Kurt Cobain, with his ratty cardigans and plastic glasses, wasn’t inventing a trend: he was showing discomfort. His was the uniform of those who didn’t want to, and couldn’t, compete with the codes of glamour. Far from the idea of a “look to copy,” grunge was an anti-fashion sustained by its very negation. There was nothing polished, nothing curated, nothing that could be defined as “clean.” That’s why talking today about clean grunge make-up sounds like a contradiction in terms, an oxymoron pushed to the extreme.

From “Kinderwhore chic” to soft goth: Courtney Love

To understand the metamorphosis of grunge in its feminine form, you have to go through Courtney Love, high priestess of what was called “kinderwhore chic.” With her looks that fused punk with the feminine glamour of Hollywood stars like Pola Negri and Jean Harlow. Her presence on stage wasn’t just music; it was a political gesture channeled through a disturbing aesthetic, halfway between fragility and violence. As Edward Meadham recalls in a piece for Another Magazine, “It was shocking to see a woman fronting a group of other powerful women, playing guitars and screaming. It was even more shocking to see a woman doing all of this using and subverting the context of the visual language of femininity: the bleached ringleted hair, the lipstick, delicate antique dresses, tiaras, Mary Janes and frilly socks. Courtney conjured a disturbing illusion of infantile prettiness and raw sexual rage.… she was the first female celebrity in a long time who wasn’t ashamed to take up space.” When we talk about grunge make-up, Love is the reference point, along with Kathleen Hanna, Kat Bjelland, Kim Deal, Jennifer Finch, Tina Bell, and many other women who defined that era’s music scene.

From mud to filter

In the ’90s, all it took was a smudged black pencil (the trick was to take a lighter and gently heat the tip of the pencil to make it softer), the burgundy lipstick borrowed from your mother’s makeup bag (or even bare lips), and a tired skin from sleepless nights to tell the world you wanted no part of it. Today, instead, grunge returns as a polished simulacrum. The skin has to be luminous, flawless, “glowy,” in contrast with a smoky eye crafted with obsessive precision. Lips are dark, but immediately tamed with a gloss that shines under the ring light. Neglect becomes a pose, imperfection becomes a tutorial, rebellion becomes a hashtag. The result is a calculated chaos, measured to the millimeter, stripped of the original despair. It’s a filtered, optimized grunge, ready to end up in a “saved” Pinterest folder but incapable of evoking the alienation, the “teen spirit” that birthed it.

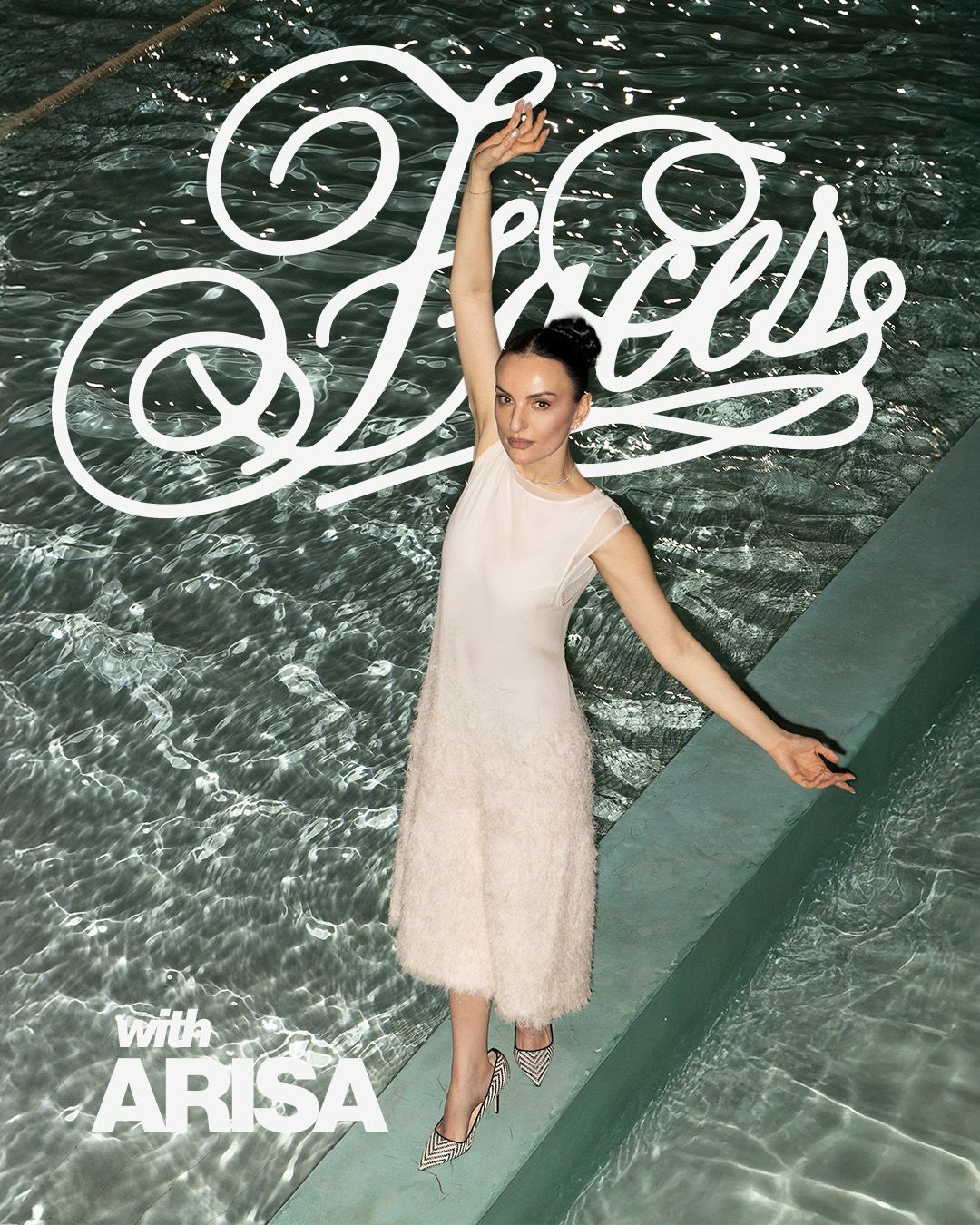

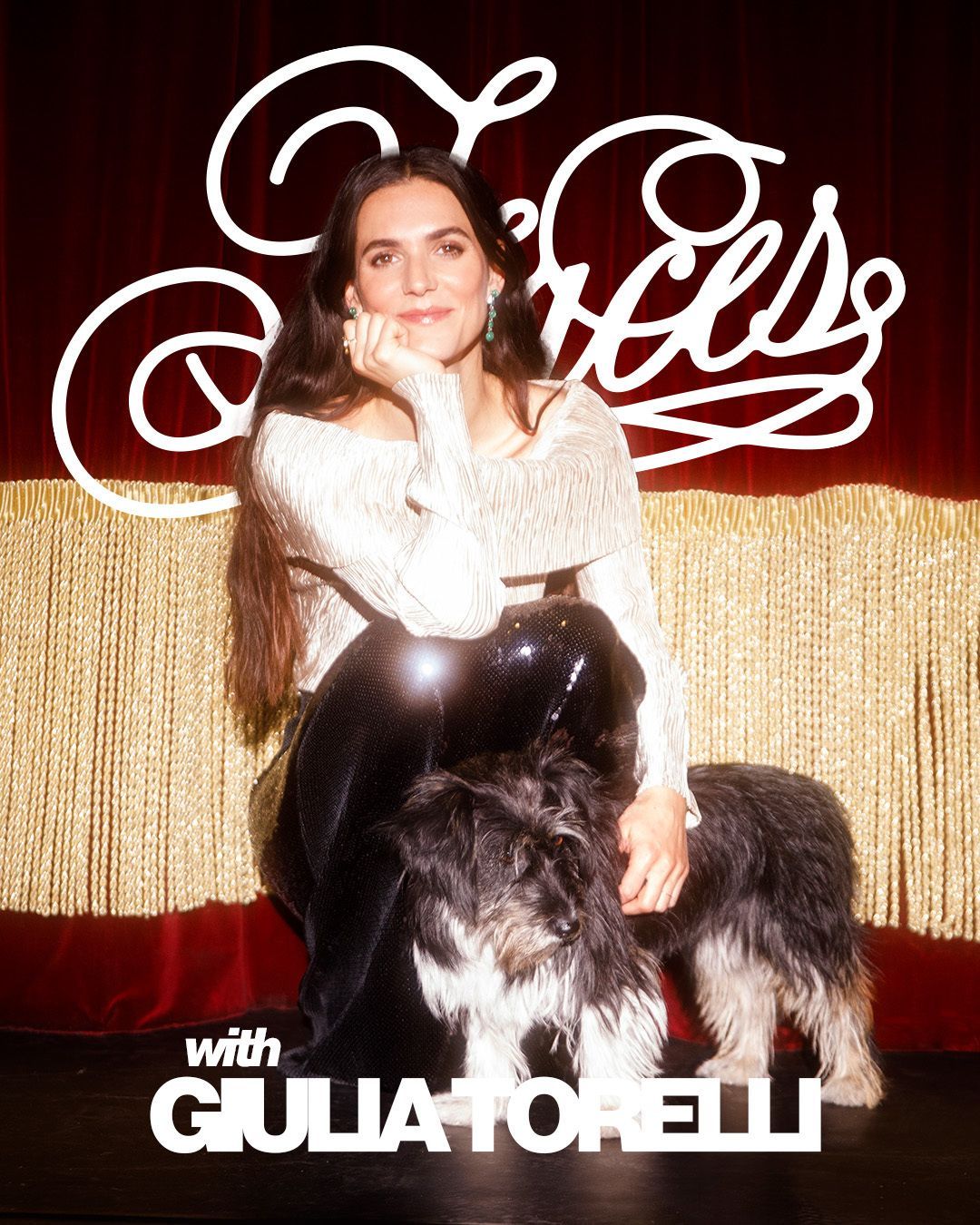

What is clean grunge makeup and how to achieve it

Unlike its origin, which didn’t care about looking coherent or attractive, clean grunge make-up is a carefully studied paradox. No more eyeliner smeared with trembling fingers in a school bathroom mirror, but a smoked black blended with precision brushes. No more lips chapped from the cold, but burgundy or plum sealed with glossy finishes catching the light. No more dull complexions from sleepless nights, but perfect, glowing skin that highlights the contrast with dramatic eyes. It’s make-up that pretends to look careless, but is calibrated to please smartphone cameras and TikTok feeds. To achieve it, all you need are soft black pencils blended carefully, dark shadows layered for smoky depth, dark lips polished with gloss, and skin rendered almost translucent with light contouring. In other words: the illusion of chaos, packaged with discipline.

The predictable trajectory of subcultures

It’s not the first time this has happened. Marc Jacobs had already demonstrated it in 1993 with the Perry Ellis collection that brought grunge to the runway, turning anti-fashion into fashion, and paying for it with his firing. Since then, the trajectory has always been the same: subcultures are born as detonations, swallowed by industry, then repackaged into harmless, consumable forms. Clean grunge make-up is just the latest chapter in this story, an aesthetic oxymoron proving how the system doesn’t destroy rebellions, it domesticates them. In other words: grunge 2.0 is no longer a rejection of the system but an aesthetic language playing with memory, somewhere between ’90s nostalgia and today’s obsession with control.

From “I don’t care” to “I want everyone to like me”

The difference between then and now lies in a single phrase. ’90s grunge said: “I don’t give a damn if you like me.” Clean grunge of 2025, on the other hand, seems eager to reassure: “Look, everyone likes me, but with a shadow of melancholy, of worn-out chic.” It’s rebellion that no longer scares anyone, carelessness calculated to please the algorithm, freedom stripped of the smell of smoke and sweat so it can be sold as a mood board. And so, an aesthetic that was once an open wound becomes a decorative scar. No longer grunge, but its polished echo. No longer a scream, but an aestheticized whisper. A rebellion that doesn’t stain, doesn’t mess, doesn’t disturb. A rebellion that is no longer rebellion. And even for a cynic like me, that hurts a little