Being tired has become too cool Doing too much is the new status symbol

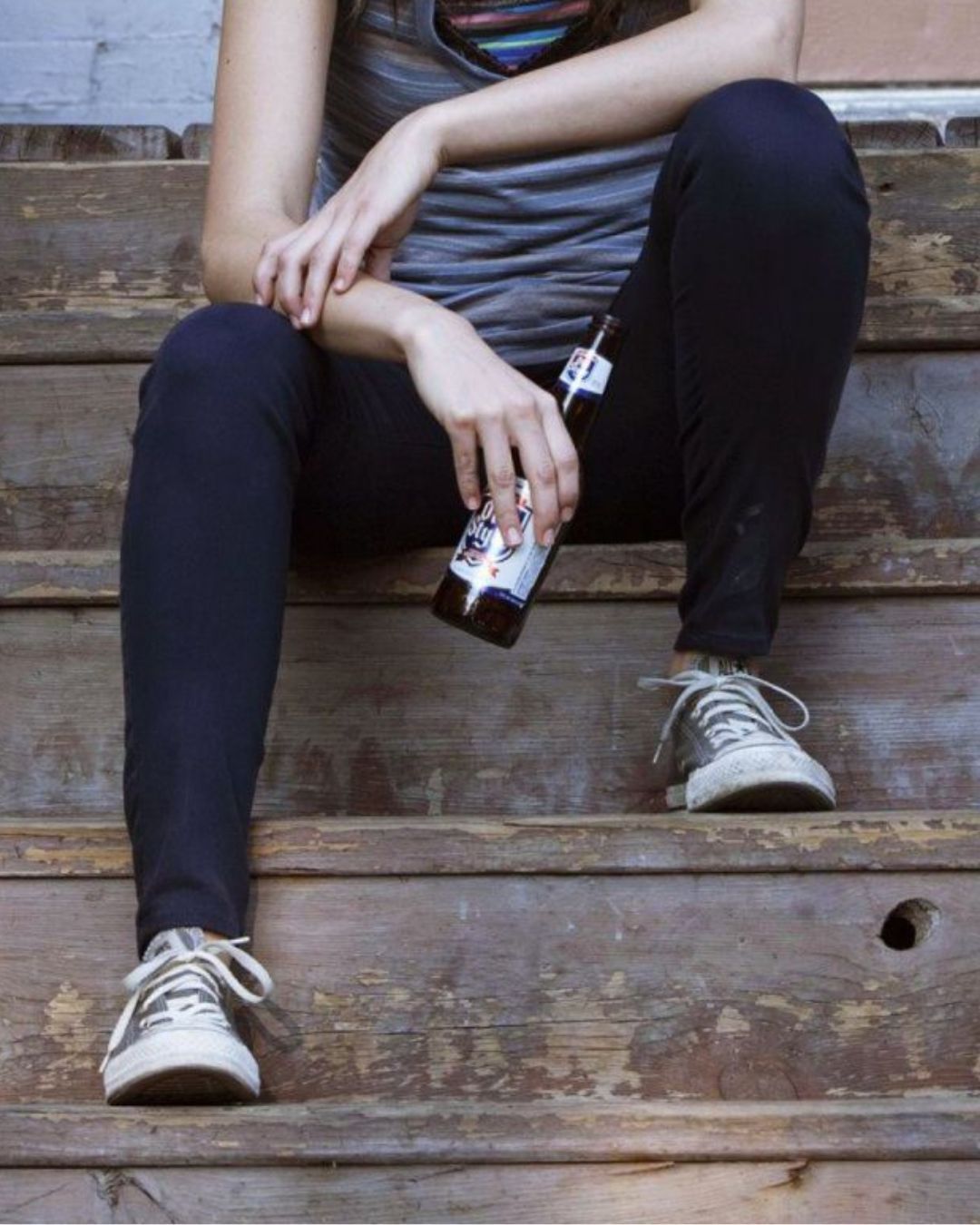

There was a time - not even that long ago - when the beauty ideal was to look exhausted, worn out, like someone who had run a marathon, worked 12 hours and then, to top it off, partied until dawn. A little substance abuse only made it better. Extremely thin, pale, elusive. The heroin chic of the ’90s turned exhaustion into glamour: deep dark circles, vacant stares and emaciated bodies. It was a controversial yet powerful aesthetic: people still talk about it and every year someone claims it’s about to make a comeback. In reality, that imagery never disappeared, it simply changed its narrative and adapted to a contemporary era where everything moves fast and rest is perceived as wasted time.

Heroin chic becomes burnout chic

Now we no longer want to look destroyed by nightlife; we want to look destroyed by work and a thousand daily commitments. The more we do, the more tired we are, the more fulfilled we feel. And we want it to show, right? The 2026 version of heroin chic celebrates a schedule that signals overload and ambition: I sleep four hours a night (if I’m lucky), I don’t have time to eat, I have 67 unread notifications, “I’m heading to the gym but I’ll be on the call!” The new trend of the moment is hyper-efficiency, and dark circles have become the badge of ambition, of being in demand and success.

Tiredness as a status symbol

Scrolling through TikTok or Instagram, the subtext is clear and this rhetoric is everywhere. The 5:30 a.m. alarm is documented as if it were a heroic act, followed by the softly lit morning routine, a cappuccino gulped down while answering emails or rushing to the office, and finally the fully booked calendar displayed as ultimate proof. It’s no longer just productivity, it’s the storytelling of productivity that romanticizes everything, making those who live a “lesser” life feel guilty, uninteresting, not strong enough. Hustle culture, openly glorified a few years ago, has now refined itself, changing its appearance but not its narrative. The slogans are less aggressive, the aesthetic softer, set to the rhythm of sunrise Pilates. No more devastating “grind now, shine later,” but rather “I’m building my dream life.” The result, however, is the same: the idea that free time is an overly expensive luxury and that exhaustion is a necessary step toward fulfillment.

@kaitlynsheppard3 it’s exhausting #mind #exhausted #foggy #blur original sound - Youranxietyislying2yew

On TikTok, the “day in my life” trend rarely shows emptiness, or a normal life where everything has its own pace. Instead, it’s all back-to-back calls, gym sessions squeezed between meetings, and optimized relaxation: multitasking skincare between podcasts while cooking and, before bed, perhaps journaling turned into an aesthetic performance, stripped of its real benefits. Everyday life becomes a curated sequence designed to demonstrate constant motion, because the strongest don’t burn out, they thrive on the movement. In this scenario, saying “I’m exhausted” translates to: I’m indispensable! I’m in demand! I’m doing something that matters!

From “day in my life” to recessioncore

The phrase “I never stop” is uttered with a hint of pride, but the problem arises when this narrative renders invisible everything that doesn’t produce spectacle: quiet rest, an empty day, a project that doesn’t launch, the conscious choice to slow down. Recession indicator? Every phase of economic recession produces a recognizable aesthetic in fashion, pop culture, and especially in our lives. In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, Hollywood responded to widespread poverty with opposite excess: glamour and fur coats on lavish sets. After the 2008 crisis, the reaction was different: minimalism and a return to basics, a distrust of ostentation. At a time when money was unstable, loud luxury felt almost embarrassing, didn’t it?

@djgoss1p Eating out is my favorite hobby so I might not survive this one chat #cooking original sound - smk_deezyy

Today we are living through another phase of instability: persistent inflation, chronic job insecurity, an inaccessible housing market for many under 35s, fewer guarantees. There hasn’t been a single, spectacular recession like in 2008; instead, there’s a feeling of continuous, normalized crisis. But unlike post-2008 minimalism, recession core isn’t just an aesthetic of saving, it’s an aesthetic of communicative hyper-adaptation. Free time becomes a variable to monetize, and life is organized like a portfolio of skills. That’s why overworking becomes seductive in a fragile economic context. If I’m always busy, always updated, always performing, then I’m less replaceable, an aesthetic translation of structural economic anxiety.

@isaavmoreno_ nos mulheres meio lizzy grant cassie nina sayers femcel girlblogger #lanadelrey #femcel #girlblogger #femcelbr #fypシ #lizzygrant #4u original sound - medici.tv

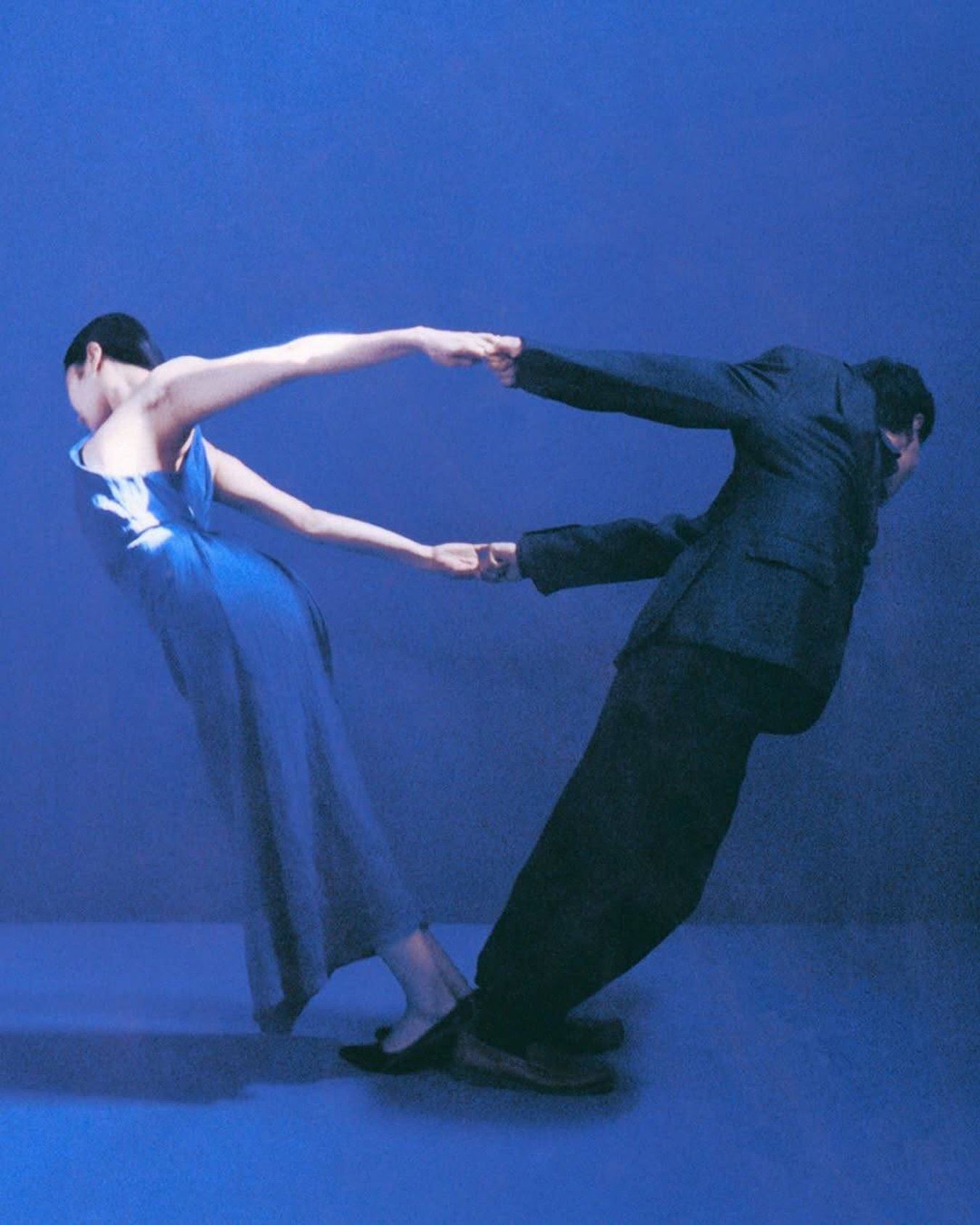

The aesthetic of exhaustion: from TV series to make-up

Today’s narrative fuel goes hand in hand with hyper-performing figures in extreme situations, on the verge of collapse. Fiona Gallagher in Shameless isn’t glamorous in the traditional sense, yet she’s magnetic. She works too much, sleeps too little, holds together a family constantly at risk of falling apart. Yet that chronic exhaustion and disproportionate sense of responsibility make her uncomfortably real. Pop culture has perfectly captured this imagery. The magnetic character is no longer the self-destructive ’90s rebel, but the hyper-performer on the brink of burnout: brilliant, hardworking, always in motion. But it’s in beauty that this narrative becomes even more explicit.

The tired make-up look is just one example (and one symptom)

The tired make-up look has spread, aiming to achieve exactly this aesthetic. Tutorials teach you how to recreate dark circles or avoid covering them completely, slightly darkening the under-eye area to achieve a lived-in, dramatic, almost Tim Burton–esque mood. Concealer would erase too much. We’d look rested and, consequently, unburdened. After years of obsession with perfectly smooth, glowing skin, the new coolness comes through a saturated, busy face. Dark circles become a crucial aesthetic detail. It’s a subtle but important difference from heroin chic. In the ’90s, dark circles evoked excess and self-destruction. Today they evoke dedication and hyper-functioning. Where they once suggested escape and nightlife in search of thrills, they now tell the opposite story.

@anymorph burn out, a short story. #selfimprovement #cinematic #motivation #healthylifestyle #filmmakers #contentcreators #aesthetic original sound - anymorph

What if we weren’t always tired?

There’s nothing wrong with being ambitious, with working hard and working well. The problem arises when exhaustion becomes an aesthetic, when dark circles stop being a signal and start being a cool detail. In the ’90s we romanticized self-destruction; today we romanticize self-exploitation. The context changes, the language changes, but the idea remains: to be desirable, you must sacrifice something of yourself. Saying “I never stop” sounds like a compliment; a packed schedule reassures us more than a free day. Everything has to be intense and high-performing, so perhaps the most subversive gesture is far less spectacular: sleeping and turning off your phone. Like any aesthetic, this one is beginning to show its cracks, and increasingly the allure shifts toward those who choose not to perform constantly. There’s something magnetic about people who don’t need to prove they’re busy to feel legitimate. Is it really so frightening to admit we haven’t pushed ourselves beyond our limits?