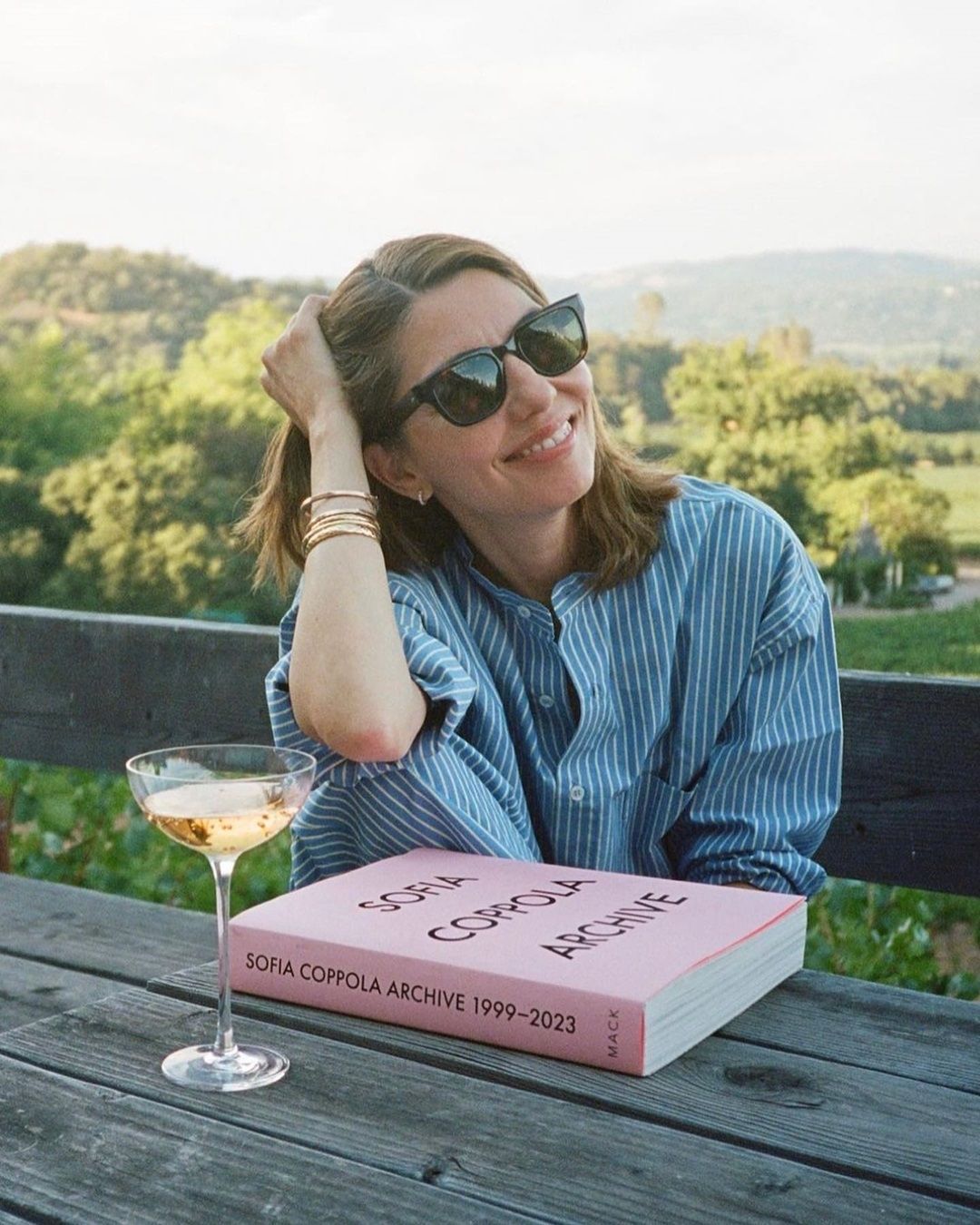

The most iconic beauty looks in cinema according to Sofia Coppola From Lauren Hutton in American Gigolo in to Catherine Deneuve in The Hunger, the muses who inspired the director's aesthetic

In cinema, make-up is never just make-up. It is visual identity, emotional projection, symbolic protection, personal memory, inner confession, unspoken desire. Even in Sofia Coppola’s world, it’s never a mere detail. It is an essential part of a visual language made of silences, bedrooms, natural light, and aesthetic melancholy. It tells of a non-traditional beauty, fragile, intimate, deeply personal. It's the barely-there pink on Charlotte’s lips in Lost in Translation, the blush on Marie Antoinette’s cheeks, the thick stroke of black eyeliner framing Priscilla’s large blue eyes. Every color, every texture, every chosen imperfection plays a narrative role: it builds the visual and emotional identity of her characters, often young women in transition, confronting a world that sees them without truly understanding them. It’s no surprise, then, that among her inspirational sources are films where make-up becomes almost a character in its own right. Films Coppola has mentioned in interviews and articles as key aesthetic references, revealing a taste that goes beyond looks and dives deep into psychology and longing. Films in which the beauty look tells not only the surface story but the interior one, quietly, yet powerfully.

Sofia Coppola’s most iconic beauty moments in cinema history span from Rita Hayworth’s hypnotic classicism in Gilda, to Kim Basinger’s unsettling sensuality in 9½ Weeks, to Lauren Hutton’s glamorous austerity in American Gigolo.

Tess (1979): The pure and tragic face of Nastassja Kinski

The beauty look of Nastassja Kinski, portraying Tess Durbeyfield on screen, embodies betrayed innocence, a trapped femininity. Created by Didier Lavergne with a touch of poetic realism, it draws inspiration from Pre-Raphaelite painting, the works of Sir John Everett Millais, Jean-François Millet, and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot: very pale, almost translucent skin, natural eyebrows, lightly flushed cheeks, lips just barely tinted. Coppola’s favorite scene is the first encounter between Tess and Alec, when he offers her a fresh strawberry and she stains her lips biting it. A small color detail that enlivens a “fresh and beautiful” face. The director has often said she’s fascinated by this kind of make-up that looks invisible, yet is the result of a perfect balance between intentional care and spontaneity. The protagonists in her films, from Lux Lisbon to the March sisters in Little Women (which she produced), draw directly from this natural aesthetic, made of natural light, rosy cheeks, and whispered lips. It’s beauty that hasn’t yet learned to defend itself, and is therefore irresistibly vulnerable.

9½ Weeks (1986): The effortless sensuality of Kim Basinger

If Tess is innocence discovering pain, 9½ Weeks is eroticism discovering fragility. A film made of visual contrasts: warm light, cool shadows, fleeting emotions. Kim Basinger’s beauty is sophisticated but cracked, perfect for Coppola’s visual world. Her beauty looks shift between control and collapse: deep red lipstick is smeared, wiped off, applied and removed in an ongoing dialogue with the scene. Her eyelids are often painted with warm metallic shadows, but never heavily. Eyeliner, when present, is soft and lightly blurred. This isn’t the femme fatale make-up of film noir, it’s lived-in make-up, one that deteriorates with the story. A visual metaphor for emotional exhaustion and loss of self. “In 9 1/2 weeks, Kim Basinger was so womanly, sexy and natural. I was in high school, and I thought she was so grown up and sophisticated. I loved her natural skin with an eyeliner – that mix.” Coppola recalls. She has always been drawn to makeup that speaks to the performance of being a woman. For her, make-up is never just aesthetic, it’s a fragile surface beneath which confused desires swirl. The protagonist of 9½ Weeks is not unlike her Charlottes, Luxes, or Priscillas: she builds herself through lipstick and shadow, only to unravel in the camera’s reflection.

American Gigolo (1980): Lauren Hutton and the quiet elegance of the Upper Class

Coppola has often cited American Gigolo not only for its tailored elegance, but for the kind of detached and minimalist femininity embodied by Lauren Hutton: “Lauren Hutton’s cool, easy polished look and soft, hot-rollered hair in American Gigolo. She had a cool, effortless glamour, like she just woke up looking like that. Her character had confidence and vulnerability, just a classic look of that era.” Here, the beauty look is all about subtraction. Hutton represents a classy, self-aware woman. Her make-up mirrors her lifestyle: precise, deliberate, never showy. Skin is perfectly groomed, with a matte but lively finish. Cheekbones are gently contoured, lips wear neutral or nude tones, often with a warm undertone. Coppola has always favored this kind of clean, almost invisible aesthetic. It’s the make-up of the aesthetic bourgeoisie, the woman who doesn’t need to shout to be seen. But even here, beneath the elegant surface, lies a compelling tension.

The Hunger (1983): Catherine Deneuve and the vamp aesthetic

Catherine Deneuve in The Hunger is iconic: alabaster skin, blood-red lips perfectly defined, graphic eyeliner, and platinum hair that looks sculpted. She’s the image of a chic vampire, dramatic and mysterious, but also a woman eternally alone, imprisoned by her beauty. This type of theatrical makeup, reinterpreted by Coppola, gains emotional depth, showing behind the icy perfection the fear of death, of loss. Make-up becomes armor and illusion, as in Priscilla, where the protagonist builds a new face to fit into her gilded cage. There too, lipsticks, eyeliner, and powders are gestures of control in a world that consumes her.

Gilda (1946): Rita Hayworth and the archetype of glamour

Rita Hayworth, with her flaming red hair, skin polished by Hollywood chiaroscuro, and perfect lipstick, embodies the idea of spectacular femininity. In Gilda, make-up is the expression of total artifice: everything is constructed desire, but with such intensity it becomes sublime. Reflecting on the film and its star, Coppola said: “I saw Rita Hayworth in Gilda as a kid, and I was like, ’That’s a woman!’ She was also an idea of a confident adult woman. Her character reveal [stayed with me], you see her hair first, and then she emerges, she had mystery and that polished 40s beauty.” So it was inevitable she would become part of Coppola’s beauty canon. Yet Coppola’s aesthetic universe isn’t made of excess, but nuance. Even in the most glamorous moments of her protagonists, there’s always one detail that breaks the spell. Because for Coppola, beauty is most powerful when it knows it’s temporary, ephemeral.