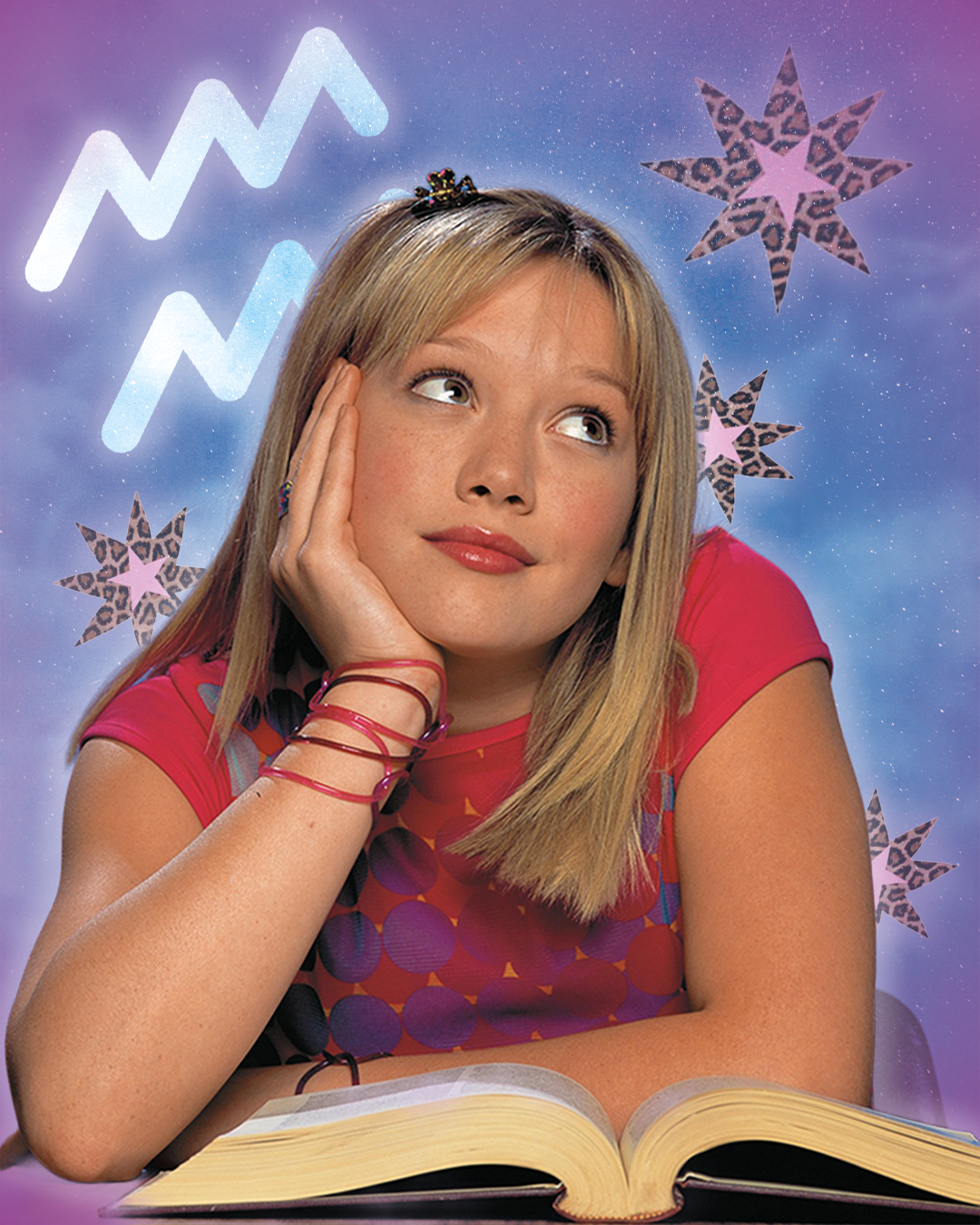

Can we trust period tracking apps? The issue is complex and relates to both privacy and reproductive freedom

In recent years, period-tracking apps have become inseparable companions for millions of people. More than just a digital agenda to note the start and end of the cycle, these platforms help predict periods, track symptoms, and identify fertile days. They guide users in understanding their reproductive health by indicating the most fertile days, suggesting habits to ease premenstrual symptoms, and even monitoring mood changes or recurring physical issues. They promise awareness, control, and autonomy. But behind the reassuring interface lies a dark side that users often don’t see: the data we input, intimate information about our health, ends up in networks of collection, analysis, and trade, in a market driven not by care but by profit, raising questions about our trust.

Femtech: a billion-dollar market, a data goldmine

The boom in period-tracking apps is part of a broader phenomenon: the Femtech sector, i.e., the technology industry focused on women’s health and well-being. Created to address the historical neglect of gender-specific medicine, this sector has grown extraordinarily. Forecasts say it will exceed 60 billion dollars by 2027, with a significant share of profits coming precisely from digital period tracking. The global market is dominated by apps like Flo, Clue, and Period Tracker, with over 250 million downloads. The public’s interest and the commercial success are clear, but unfortunately, they rest on a fragile mechanism: if the service is free, the real currency is sensitive data. These apps thus become not only wellness tools but also cogs in an invisible market of targeted advertising, data brokers, and global ad platforms. Many people believe these apps are just for remembering period dates. In reality, they encourage logging a surprising amount of details: contraceptive use, sexual activity, mood variations, daily energy levels, medications taken, or pregnancy intentions. Together, this data creates an extremely detailed profile of users’ daily lives, highly valuable because it touches one of the most sensitive areas of life: reproduction. As researchers from the Minderoo Centre for Technology and Democracy at the University of Cambridge explain, this type of information, analyzed, packaged, and resold for advertising or commercial purposes, represents a true “goldmine for big tech.”

The risk of reproductive surveillance

The gravest danger concerns the use of menstrual-cycle data by governments or law enforcement. In the United States, after the overturning of Roe v. Wade, many women began deleting these apps for fear that data could be used in court as evidence of illegal abortions. A simple logged delay could turn into an investigative clue. And the issue isn’t limited to America. In politically unstable or repressive countries where abortion remains criminalized, or in contexts where reproductive freedom is under attack, cloud-stored data can be seized and used against the very people who generated it. This is not science fiction but a concrete possibility. A logged cycle delay could become incriminating information.

Privacy, between promises and contradictions

Digital privacy concerns aren’t new. Back in 2019, Privacy International reported that over half of the analyzed apps, precisely 63%, automatically transferred information to Facebook, often without users’ awareness. In later years, under media and public pressure, some platforms reduced the number of integrated ad trackers, and many introduced so-called anonymous mode, allowing use without providing identifying details like name or email address. Remember the Flo Health case? In 2021, a Wall Street Journal investigation revealed that the app, one of the world’s most popular, was sharing with Facebook whether a user was on her period or trying to conceive, without explicit consent. The scandal led to a class action against Meta, Flo, Google, and Flurry. All companies except Meta settled out of court; Meta was brought to trial and recently convicted of purchasing reproductive health data from Flo without users’ consent, for marketing purposes. Yet problems persist. A King’s College London study on twenty fertility and period apps showed that all of them shared personal information with third-party advertisers, and in fewer than half of cases was this practice openly disclosed. In Europe, the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) classifies menstrual data as “special categories,” like genetic or ethnic data, but reality shows regulation isn’t enough: loopholes remain, especially when apps are developed by companies outside the EU.

@lutealgirl your body is your business! #cyclesyncing #periodtips #hormonehealth #cycletracker #luteal #periodapp #ovulation #privacy The Bug Collector - BEN SCOTT

Beyond marketing: risks in the workplace and identity

Period-tracking apps aren’t just wellness tools: they reveal habits, desires, and vulnerabilities. The potential misuse of such data isn’t limited to marketing or targeted ads. Some employers have included these platforms in corporate welfare packages, an apparent gesture of care that actually opens disturbing scenarios: companies could use them to know if an employee is planning a pregnancy, influencing hiring or promotion decisions. There’s also another layer of risk, less discussed but equally important. The mere presence of such an app on a phone can reveal information about a person’s gender identity, with sensitive consequences for those who don’t feel safe in their social environment. For trans people in particular, using a period-tracking app can become an unwanted indicator, exposing them to discrimination or violence. This shows the problem isn’t only technological but deeply social and cultural. And yet, their popularity grows, partly because menstrual health remains one of the least studied areas in medicine. Digital tools promising quick answers are irresistible, especially for those living with conditions like endometriosis or PCOS, which take years to diagnose.

What future? Possible alternatives and new scenarios

Not all the news is negative. Some apps have reduced ad trackers and improved policy transparency. The introduction of anonymous mode is an important step, as are apps that store data only locally rather than in the cloud. However, many point out these measures are insufficient without stricter regulation and real enforcement of existing rules. So the key question remains: can we trust platforms whose profits are based on circulating our most intimate health data? Experts’ advice is clear: choose only apps that don’t store data in the cloud, and be wary of free ones that promise much without asking anything in return. Some even imagine more radical alternatives, like apps supported by national health systems, designed to prioritize public health over profit. Such a solution could restore trust and reduce the risks of the data market, offering safe tools without forcing people to trade away their intimacy for seemingly free services. In short, whether we can trust period-tracking apps has no simple answer. The only certainty is that at stake is not just targeted advertising, but digital privacy rights, and, in some cases, reproductive freedom itself.