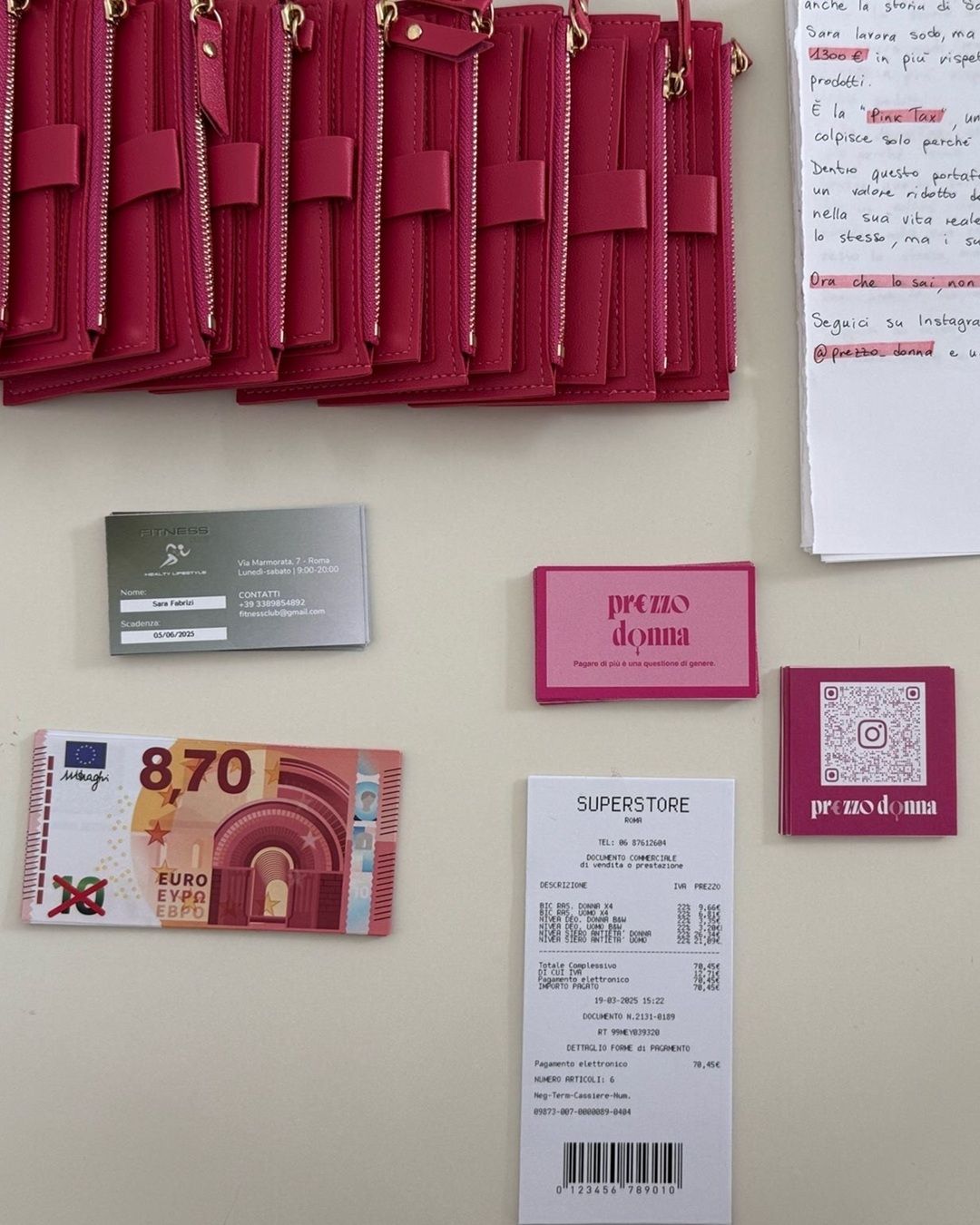

Feminicides in Italy: the illusion of protection and the reality of failure A phenomenon that shows no sign of stopping

In 2024, femicides in Italy continued to rise alarmingly: as of September 1st, 65 women had been killed, out of a total of 192 intentional homicides. This means that one in three victims was a woman, almost always murdered by someone close to her. In the vast majority of cases, the perpetrator is a partner, ex-partner, or a family member. These are not isolated incidents, but part of a deeply rooted system of domestic violence, control, and possession, fueled by structural and cultural gender inequalities.

International and national data

According to the United Nations and the World Health Organization, as early as 2017, 58% of women murdered worldwide were killed by a partner or relative. Italy fits this pattern perfectly: over 80% of femicides occur in intimate or familial relationships, as confirmed by the Italian Ministry of the Interior. ISTAT adds that although overall homicide rates have dropped over the last 20 years, femicides remain stable, with women killed in 90% of cases when the aggressor is their partner.

When home becomes a trap

For many women, the domestic environment is not the safe haven it should be, but the most dangerous place. Femicides often occur after long periods of psychological and physical abuse, triggered in many cases by the woman’s decision to separate or become independent. Every act of autonomy can become a deadly risk, every attempt to report abuse a race against time.

Media and femicides: a toxic narrative

The media portrayal of gender-based violence in Italy remains deeply flawed. Murders are often described as “crimes of passion,” “tragedies of too much love,” or the killers are portrayed as “nice guys,” “kind,” themselves victims of jealousy or loneliness. This language not only distorts reality but minimizes the perpetrator's responsibility and ends up romanticizing violence.

As I wrote in my book Gli Svedesi lo fanno meglio, published by Rizzoli, femicide is traditionally divided into three narrative models by the media:

- The high-profile case, like that of Giulia Cecchettin, treated like a thriller, with morbid details and misplaced pathos.

- The routine coverage, where violence is trivialized and lost in a stream of news using stereotypes like “sick love” or “sudden outbursts.

- The tragedy of loneliness, often involving elderly or vulnerable victims, where the crime is excused as an act of desperation, with the victim barely mentioned.

New laws, old problems

In 2024, Italy introduced new legislative measures to combat gender-based violence, including:

- Mandatory electronic bracelets to monitor those accused of violence.

- Harsher penalties for repeat offenders, including the introduction of “deferred flagrante delicto,” allowing arrests based on video evidence after the fact.

- Updates to the Red Code law to speed up judicial responses to reports.

However, the impact of these reforms remains limited. Electronic monitoring devices, for instance, often fail due to technical issues or poor network coverage. Even when functional, they’re not always activated in time or used effectively. The tragic case of Samia Bent Rejab, murdered during the two hours a week her violent husband was allowed out despite house arrest, is proof of this failure.

The long list of institutional failures

Samia is not alone. Celeste Palmieri, Roua Nabi, Concetta Marruocco, Camelia Ion—women who had already reported their aggressors and were killed anyway. In too many cases, protection comes too late or not at all. So-called “warning crimes”—stalking, threats, abuse—are not taken seriously until they escalate into tragedy. This is where the state fails: by not preventing, by not listening.

And the victims? Still unheard

The inadequacy of institutional responses fosters a climate of distrust and resignation. How can we continue to ask women to report violence if they are not protected? If the system is not only inefficient but contributes to creating more danger? Who is responsible for rehabilitating perpetrators, for cultural prevention, for dismantling toxic masculinity?

The weight of intersectional discrimination

Finally, we cannot ignore the role of ethnic discrimination in how femicides are reported and handled. When the victim is foreign or the perpetrator is from a minority, media coverage is often even more superficial or entirely absent. Every life should have the same value. But this principle gets lost in the headlines.

We’re angry, and rightly so

Our protection system has failed too many times. The measures exist, but they are not enough. We need a cultural revolution, widespread education, and a collective commitment to recognize the signs of violence and act before it’s too late. Every death must be treated with the respect and seriousness it deserves. Because we cannot keep dying like this. And yes, we are tired. And yes, we are angry. And we must stay that way.