Inclusive and feminist architecture: is it possible? Empathy, accessibility, and care as principles of architectural and urban design

Rethinking spaces from an inclusive and feminist perspective represents a profound shift in outlook that concerns the way we choose to live together. Above all, it means recognizing that space is never neutral, and that buildings and infrastructures shape behaviors, relationships, possibilities, and limits of everyday life. Talking about feminist architecture does not mean applying an ideological label to projects, but acknowledging a reality: for too long, space has been designed by a few and for a few, ignoring the needs and fears of a substantial part of the population.

Space is not neutral, so feminist architecture is possible

For decades, architecture and urban planning have been built around a subject considered “standard”: adult, able-bodied, male, economically productive, without caregiving responsibilities. Anything that diverged from this model, such as women, children, older people, people with disabilities, caregivers, was treated as an exception, something to be adapted later. This approach has produced cities that appear functional, but are often hostile in practice. Narrow or damaged sidewalks, dark underpasses, isolated stations, dormitory neighborhoods without nearby services. Spaces that, while formally public, are in fact inaccessible or unwelcoming for many people. A feminist, or rather transfeminist, architecture overturns this approach: it does not design for an ideal body, but for real bodies. It starts from everyday experience and from the inequalities that run through urban space.

@poli.her.o Le #donne occupano spazi è la #tesi con cui Adele @analog_adel si è laureata al #Polimi. Un giro per #Milano diventa una rilettura di #genere della #città #urbabistica #gendergap #genderequality #laurea #architettura #feminismo LA DOLCE VITA - Fedez & Tananai & Mara Sattei

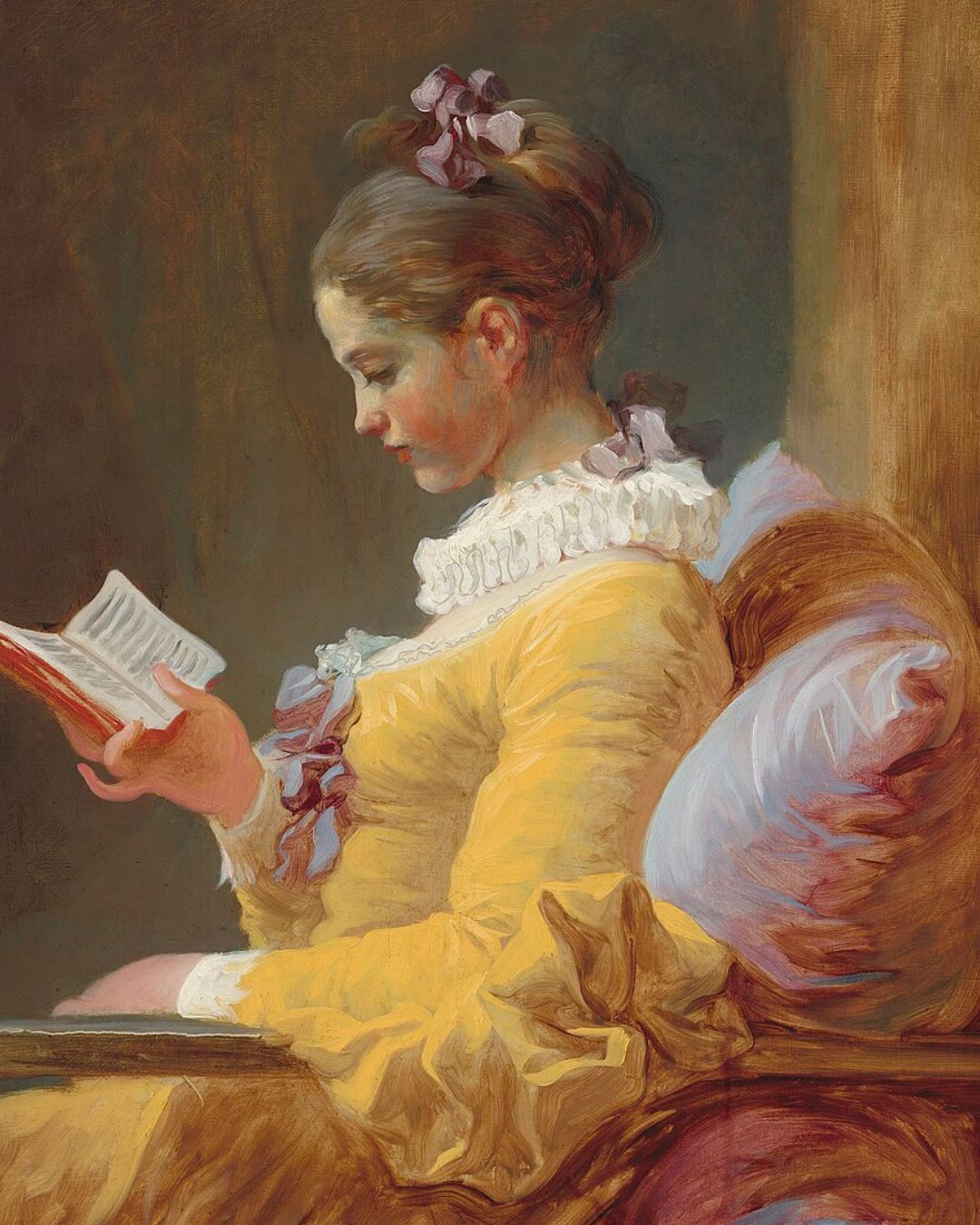

Empathy as a design tool

Empathetic architecture means designing by putting oneself in the shoes of those who will move through that space. Not only through data and technical standards, but by listening to stories, habits, fears, and desires. A simple but emblematic example is public lighting. A well-lit street is not just a matter of aesthetics or energy savings: it is a matter of freedom. The possibility of walking home in the evening without anxiety radically changes one’s relationship with the city, especially for women and marginalized communities. Likewise, a public transport stop that is visible, open, crossed by diverse flows, and not isolated becomes a space that reduces vulnerability. Empathy, in this sense, is not an abstract concept but a concrete design criterion.

@thersaorg What if your city wasn’t designed with you in mind? For most women and non-binary people, it wasn’t. But in Glasgow, that’s starting to change. Read more on RSAJournal+ #RSAJournal #FeministUrbanism #CityPlanning #Glasgow #Architecture #InclusiveDesign original sound - theRSAorg

The city seen through the eyes of caregivers

Another central aspect of feminist architecture concerns care work. Even today, disproportionately, women are responsible for caring for children and older people. This results in complex, fragmented, non-linear journeys. Cities, however, continue to be designed according to the home–work scheme, ignoring this reality. An empathetic and feminist urban planning instead asks:

- Are essential services reachable on foot or by public transport?

- Are spaces accessible with strollers, wheelchairs, shopping bags?

- Are there benches, public toilets, places to stop and rest?

Answering these questions does not only improve women’s lives, but makes the city more livable for everyone.

Perceived safety and real safety

The issue of safety is often addressed in a reductive way, as if it coincided exclusively with surveillance and the presence of law enforcement. Empathetic architecture proposes a different vision. Safety also, and above all, arises from the quality of public space. Well-maintained, lived-in spaces, crossed by different functions at different times, reduce the risk of violence and isolation. Visibility, lighting, mixed uses, and constant maintenance are tools as powerful as any camera. It is the opposite of militarizing the city; it means making it inhabited and shared.

@studio.null What Would a Real Feminist City Look Like? #books #booktok #feminism #urbandesign#city #barbie original sound - Studio Null

Accessibility as a principle, not an add-on

From a feminist perspective, accessibility is not optional nor a final concession. It is a founding principle of design. This means moving beyond the logic of “special solutions” for a few and building spaces that work for as many people as possible. Ramps, functioning elevators, clear signage, intuitive pathways are not luxury features: they are tools of equity. Talking about feminist architecture also means questioning decision-making processes. Who sits at the tables where decisions are made about what a square or a street will look like? Who is listened to, and who is not? Involving citizens, associations, committees, and people who live in those places every day is an integral part of an empathetic approach. Participation is not a slowdown, but an investment in the quality of the project.

From the margins to the center

Empathetic and feminist architecture brings to the center what has long been marginalized: everyday experience, vulnerability, care, slow time. It does not propose “cities for women,” but better-designed cities. It is a concrete response to urban inequalities, because it changes the questions even before the solutions. All of this requires political will and the courage to challenge established models. It is a necessity.