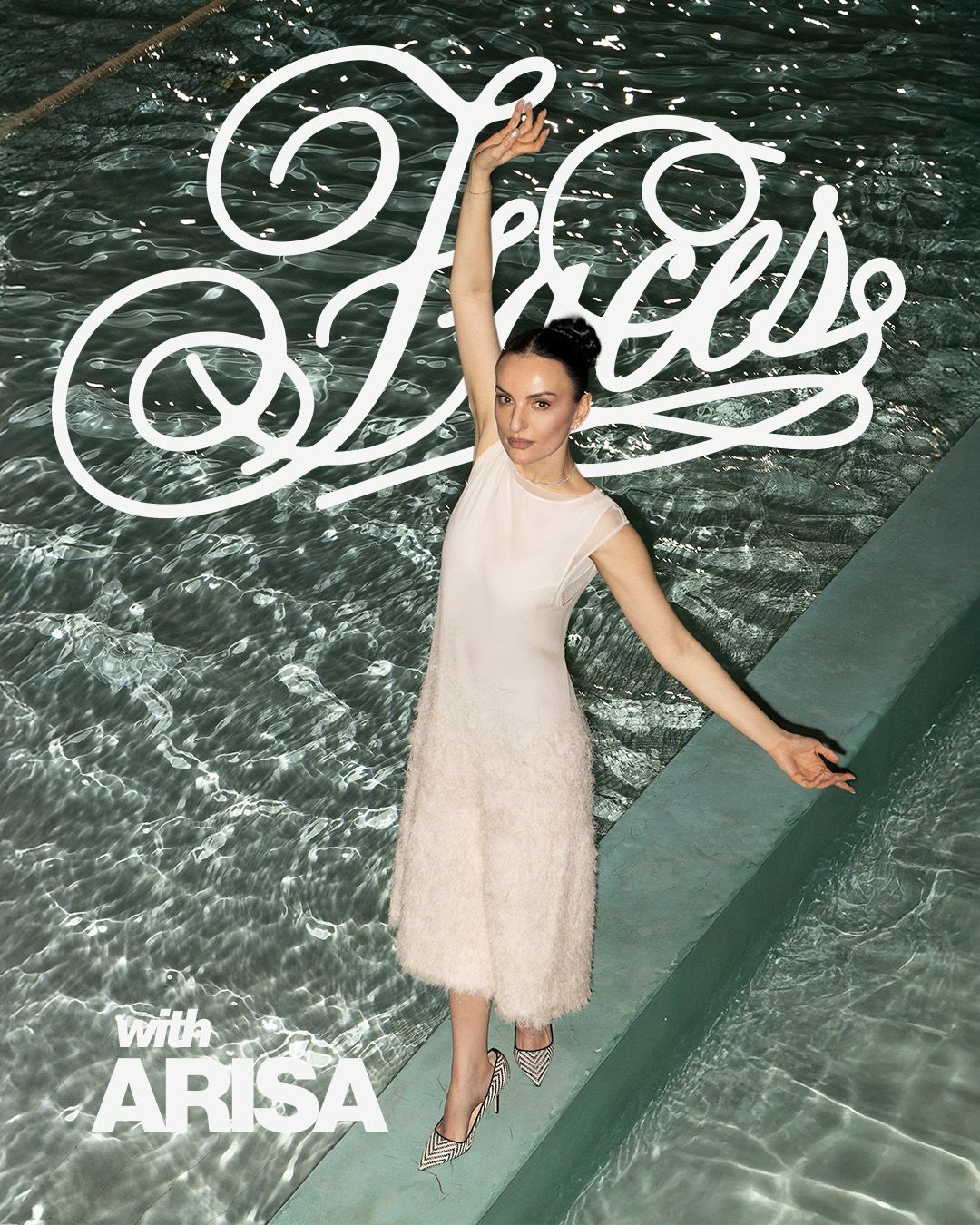

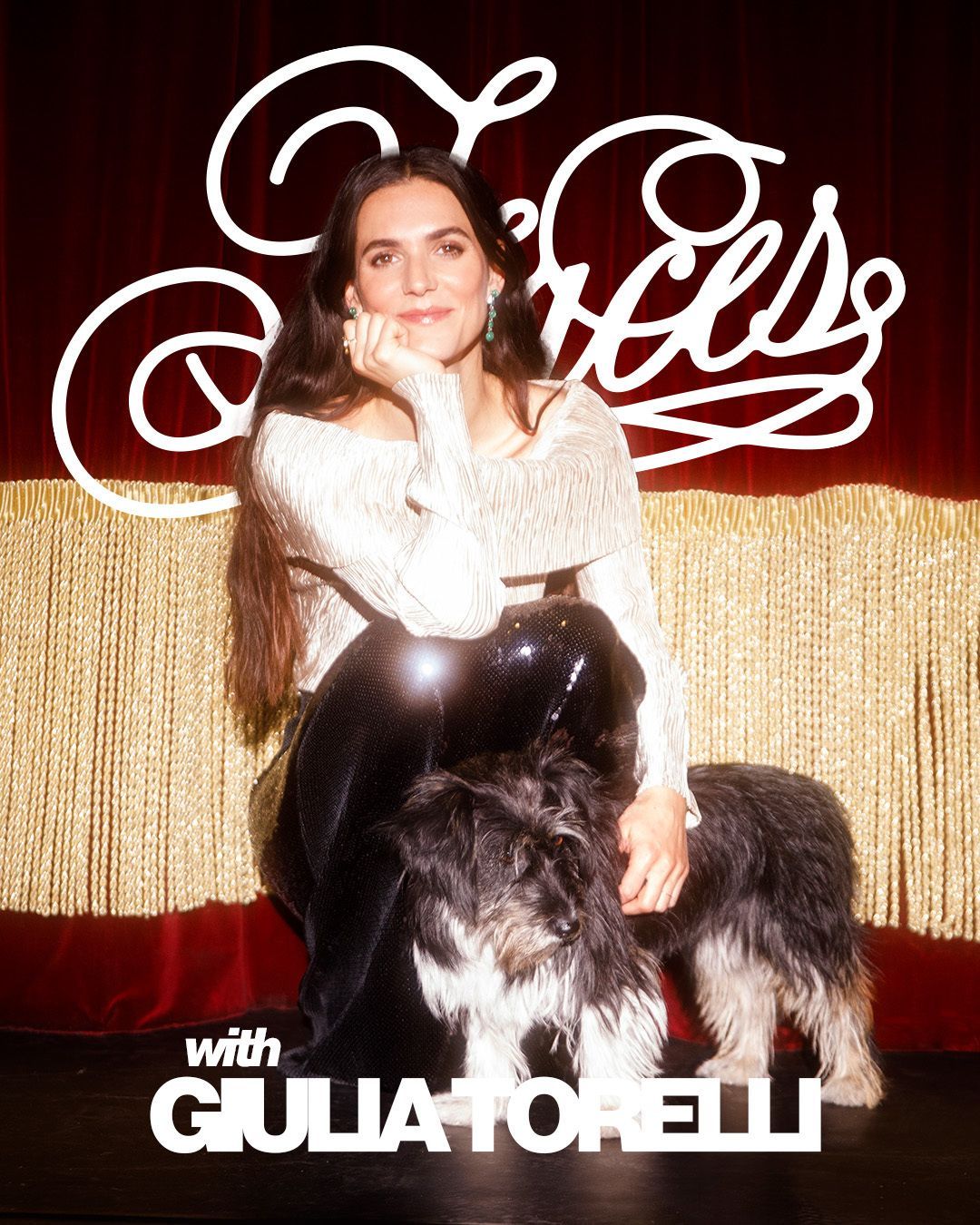

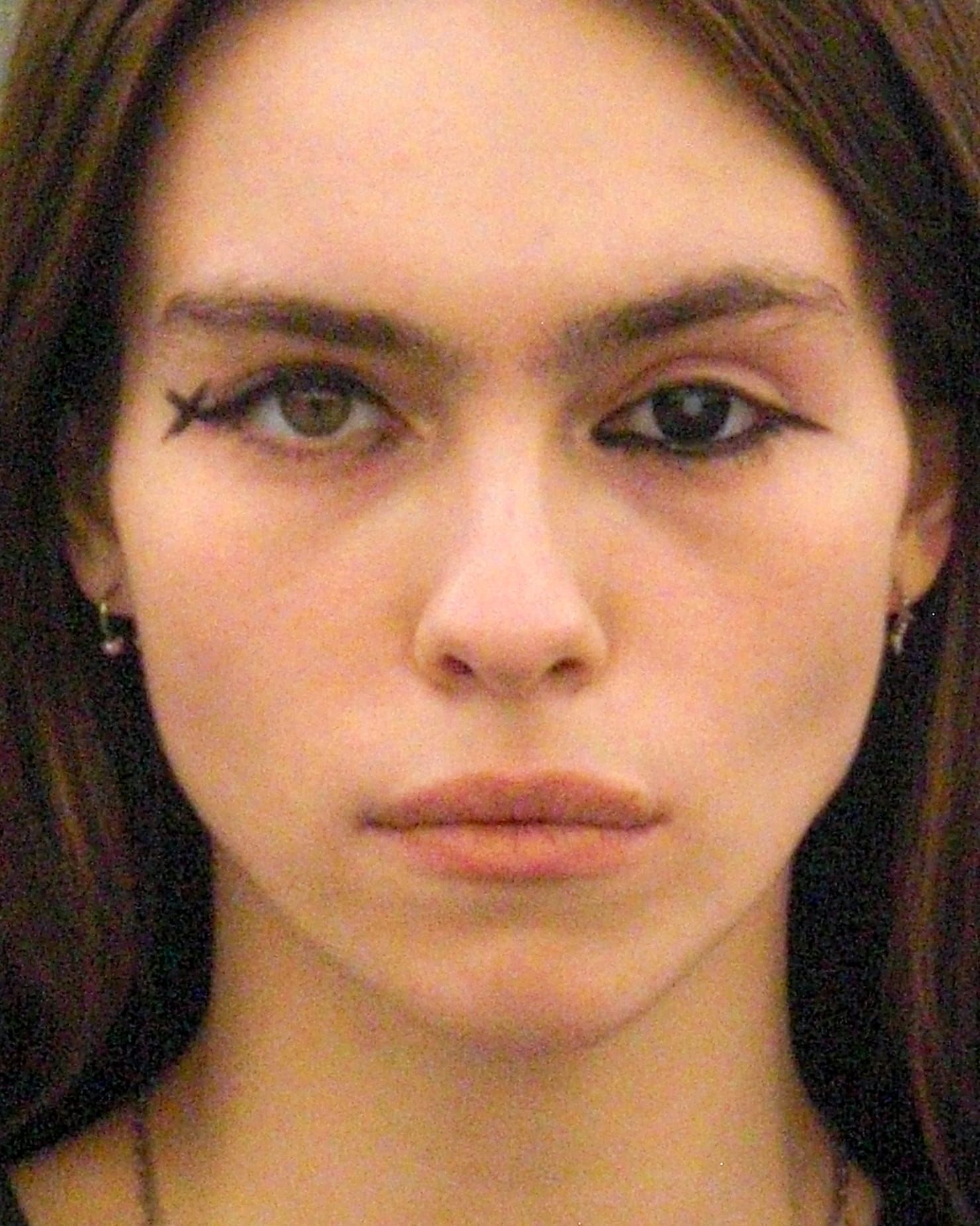

"The aesthetic philosophy of ugliness challenges dominant standards" Interview with Ugly Roscino, make-up artist for the ugly

Ugly Roscino is a different kind of make-up artist. His approach is different, his style is different. Different from what? From the standard, from soft glam and cozy make-up. On his Instagram profile, the platform where we reached out to him for an interview and to make him the very first guest of our new format “Under the Beauty Radar”, born from the desire to discover, to escape, and to spotlight new artists who challenge (or completely ignore) current trends in order to pursue an alternative kind of research, he defines himself as a Priestess of Ugliness, perfectly summarising his philosophy. We wanted to explore it further in a conversation that moves from aesthetics to politics, all the way to philosophy.

Interview with Ugly Roscino, the make-up artist of ugliness

Describe your aesthetic in three words

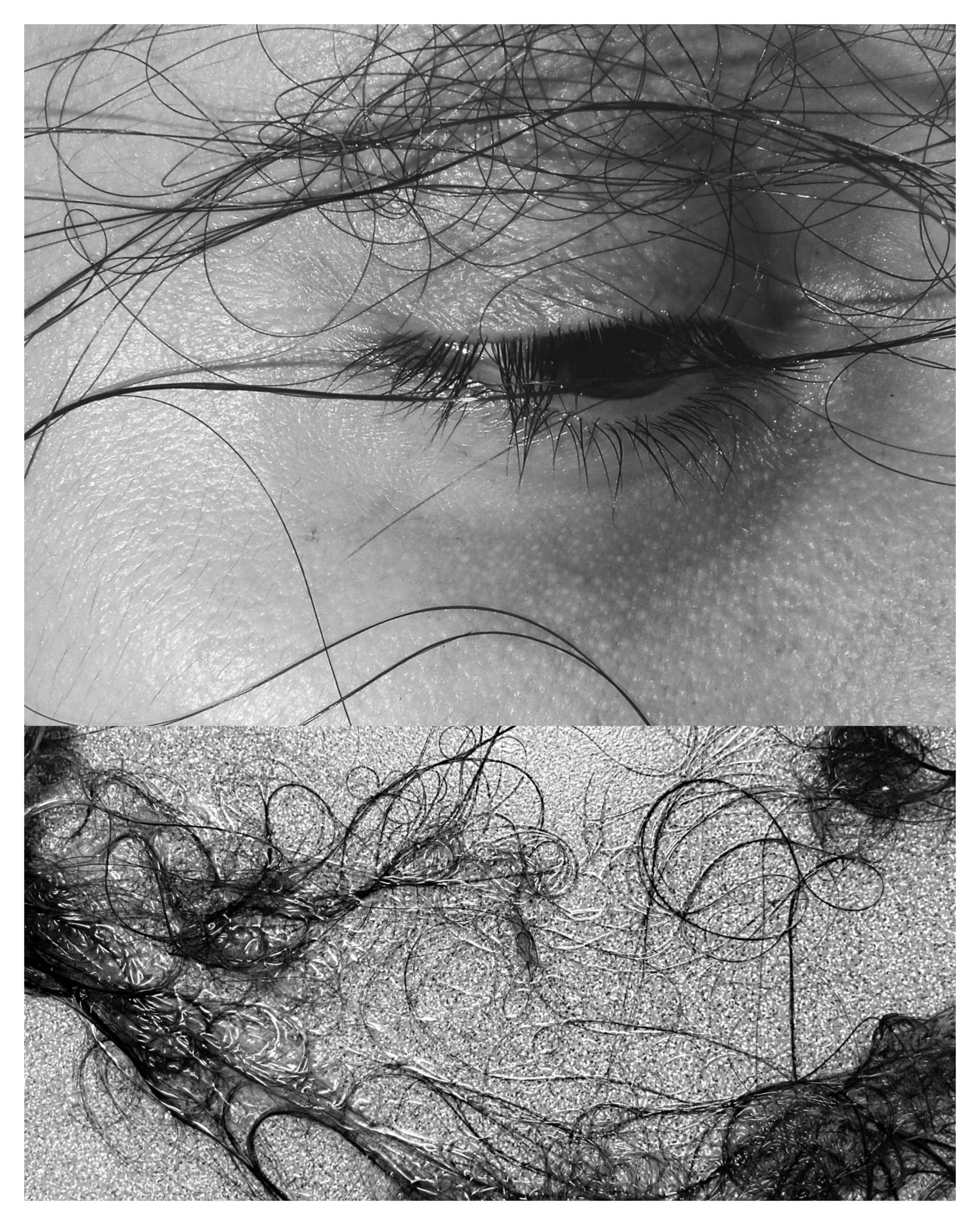

Raw, grotesque, subversive.

Can you tell us about your professional journey and the evolution of your visual language?

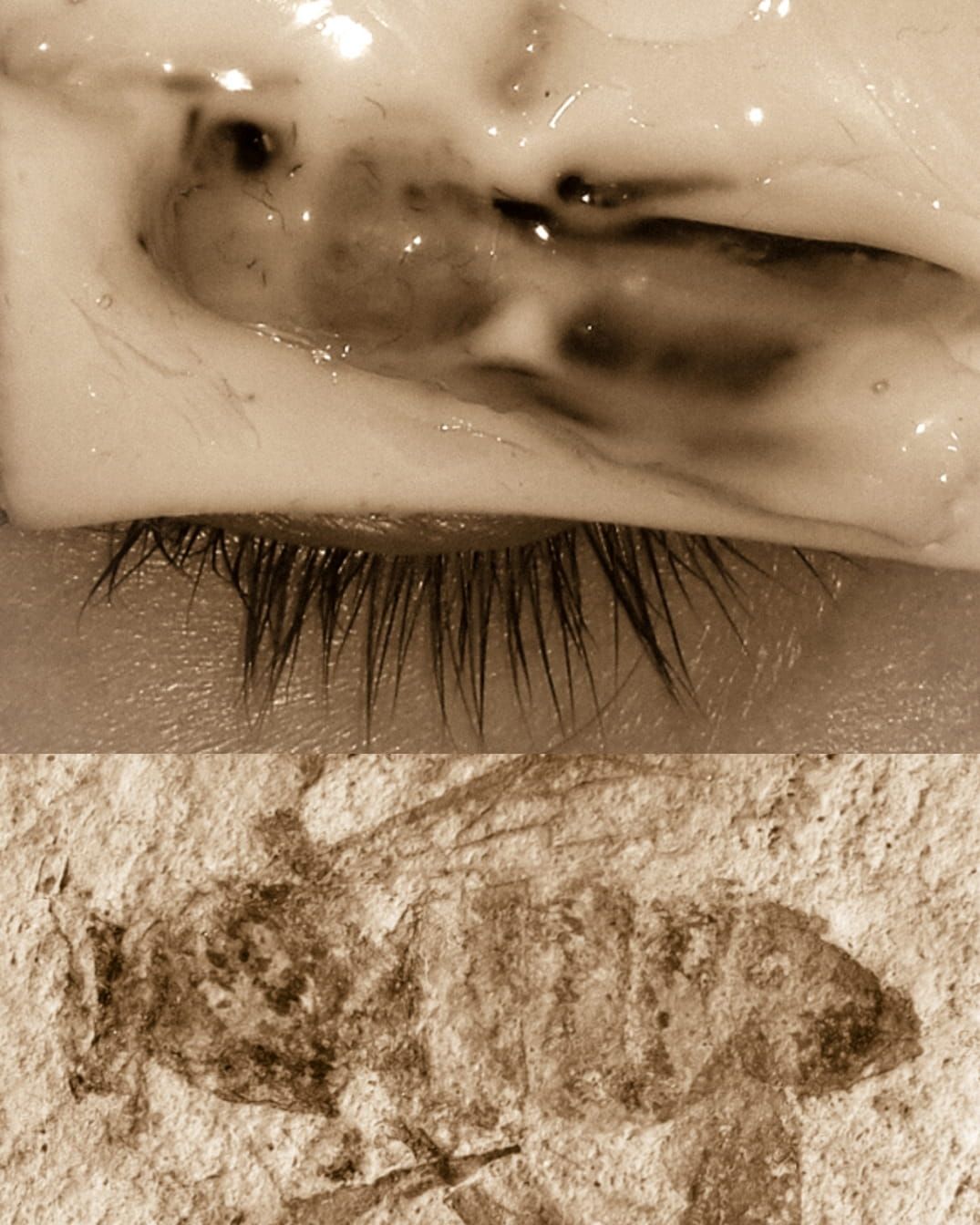

I come from a small town in Puglia, where the idea of fashion has always felt very distant. I attended an art high school, where I immediately nurtured my passion for art, philosophy and history. At 17, I officially started doing make-up for my friends for different kinds of events, gaining a lot of hands-on experience. At the time, however, I was convinced I couldn’t turn this passion into a real job, so I decided to study graphic design in Milan. Meanwhile, I began assisting professional make-up artists and doing a lot of grunt work. I’ve always worked extensively on social media: Instagram helped me give visibility to my work. My style has always been quite messy, imprecise, and this pushed me to question why I was so drawn to the grotesque and the imperfect. During my research, I discovered the first philosophy manual dedicated to ugliness, Aesthetics of Ugliness (1853) by Karl Rosenkranz. That was the turning point: I devoured page after page, research after research, and that line of thought completely unleashed my creative spirit, allowing ugliness to take increasing ownership of my visual language.

Why is ugliness, as an aesthetic philosophy, political?

I like to start from a reflection by Michela Murgia on the difference between the pre-political and the political. The pre-political is the moment when we become aware of a discomfort we experience personally and try to solve it on an individual level. Once it’s resolved, the problem ceases to exist for us. Politics, on the other hand, means recognising that this discomfort is the symptom of a systemic distortion that affects others as well. It means wanting to address it not just for yourself, but for the collective. In this sense, ugliness, as an aesthetic philosophy, becomes political. Ugliness – whether aesthetic or moral – is never purely individual: it concerns all of us, questions dominant standards, and fights stereotypes and social barriers, opening up spaces of acceptance and new possibilities.

Your work seems like a direct response to the idea of clean beauty, or to make-up as a tool meant to enhance and beautify. Why does it make sense for you to overturn this vision?

I don’t experience my work as a direct response to clean beauty, nor as a rejection of make-up as a tool for enhancement. I’m simply not interested in working within that narrative. My goal isn’t to oppose the idea of beauty, but to fight for ugliness to be accepted just as much as beauty within society. In 19th-century aesthetics, ugliness was often understood as a reaction to beauty: a negative or subordinate value whose purpose was to exalt the ontological meaning of beauty itself. For me, instead, they are two distinct values that communicate with each other, but are not in conflict. It’s society that constantly places them in opposition. My aim is to reach a point where we stop talking about beauty and ugliness altogether, and instead focus on identity and personal expression, without barriers. A space where everyone is free to celebrate beauty, ugliness, or move fluidly between the two.

A make-up trend you hate and one you love

I’ve never had a positive relationship with trends – quite the opposite: I find them deeply alienating. In my opinion, they don’t encourage the construction of a personal identity, but instead push toward a collective, standardised aesthetic made of labels. The moment we define something as trendy, we automatically include and exclude, creating boundaries and hierarchies that have little to do with individual expression. Many recent trends, especially in make-up, feel empty and superficial to me: they don’t convey a message or a vision, but focus solely on appearance, performativity, and the pursuit of immediate approval, likes. In this sense, trends are almost my nemesis. I’ve never followed them and they’ve never truly interested me, because my work comes from the opposite need: using make-up as a personal language, not as a code to replicate.

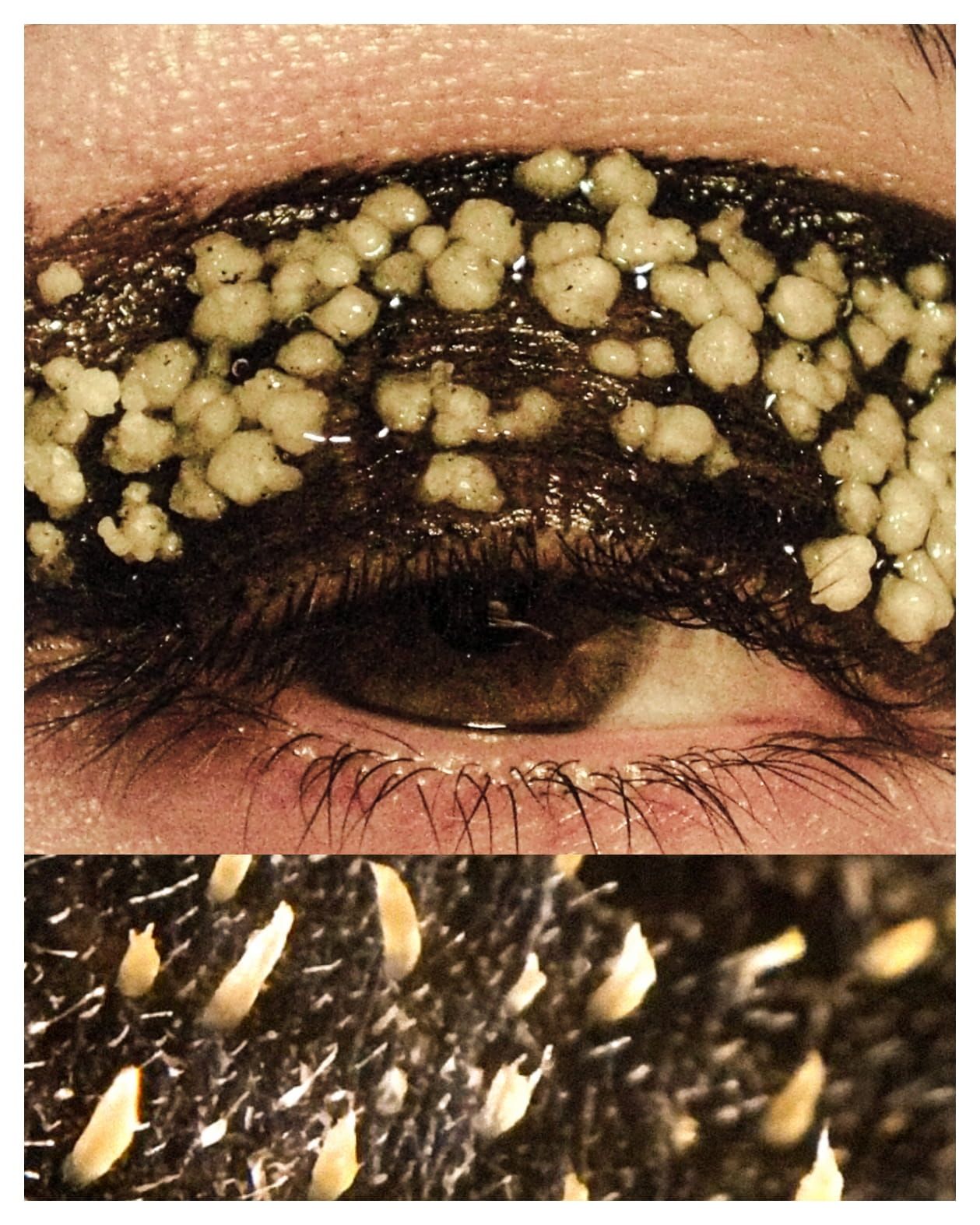

What’s something that’s always in your make-up kit?

Pigments, without a doubt – the strangest and most colourful ones. I prefer creating my own products and mixing them together, always making sure to check the compatibility of ingredients and components. Lip products and mascaras are the ones I love customising the most and giving my personal touch.

What would you say to someone who wants to become a make-up artist but doesn’t have a “traditional” idea of beauty?

I’d say: don’t be afraid to go against the current. Stay on your path, with determination, and don’t let yourself be discouraged. The definition of beauty is changing, and those who dare to develop their own language – even far from traditional schemes – will find space to express themselves freely.

What inspires you?

My main sources of inspiration are books on the aesthetics of ugliness, especially On Ugliness by Umberto Eco, an itinerant essay exploring a vast iconography of nightmares, terrors and unsettling demons. I also draw a lot from late ’80s and early ’90s cinema, particularly niche Eastern European films. I deeply hate using Pinterest! I prefer a good book or a well-made documentary. Sometimes even objects I encounter on the street or around me can suggest textures or colour combinations. A perfect example: one day, while walking through a famous park in Paris, I came across a very bizarre mosaic created by an accumulation of pigeon droppings. I immediately took a photo, and shortly after created a make-up look inspired by that very accumulation. That’s how my brain works – it doesn’t follow fixed mechanisms or predefined schemes.

Which make-up artists inspire you or do you admire the most?

The ultimate mother of this visual language – from whom my work undoubtedly draws inspiration – is Inge Grognard! I’m an enormous fan of her work and aesthetic, especially all the projects she created with Martin Margiela. Other make-up artists I deeply admire for their creative talent are Isamaya Ffrench, Daniel Sällström, Valentina Li, Morgane Martini and Cécile Paravina. Valentina and Morgane, in particular, have been and continue to be my mentors. I’ve learned so much from them and I’m endlessly grateful to have had the honour of working alongside them.