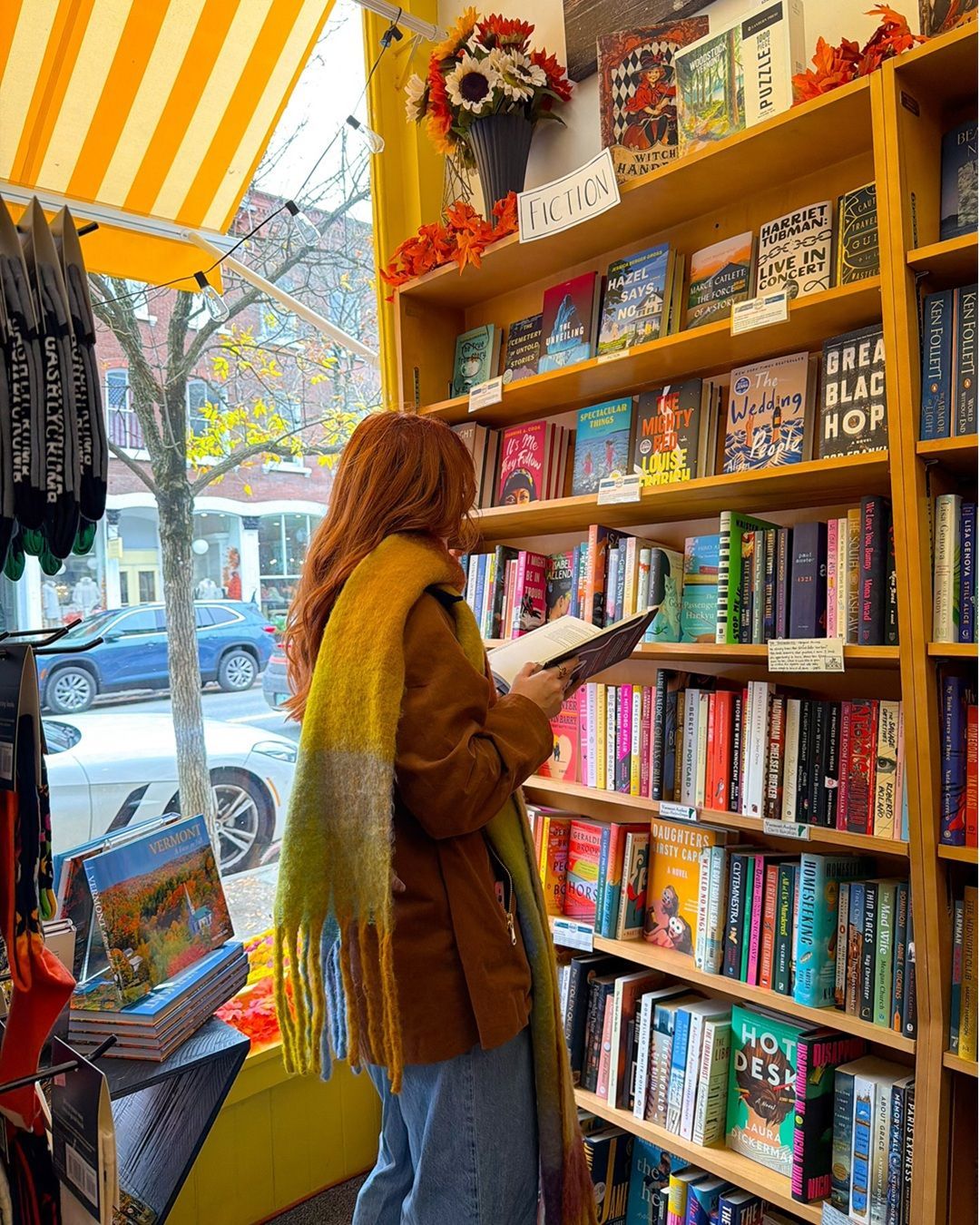

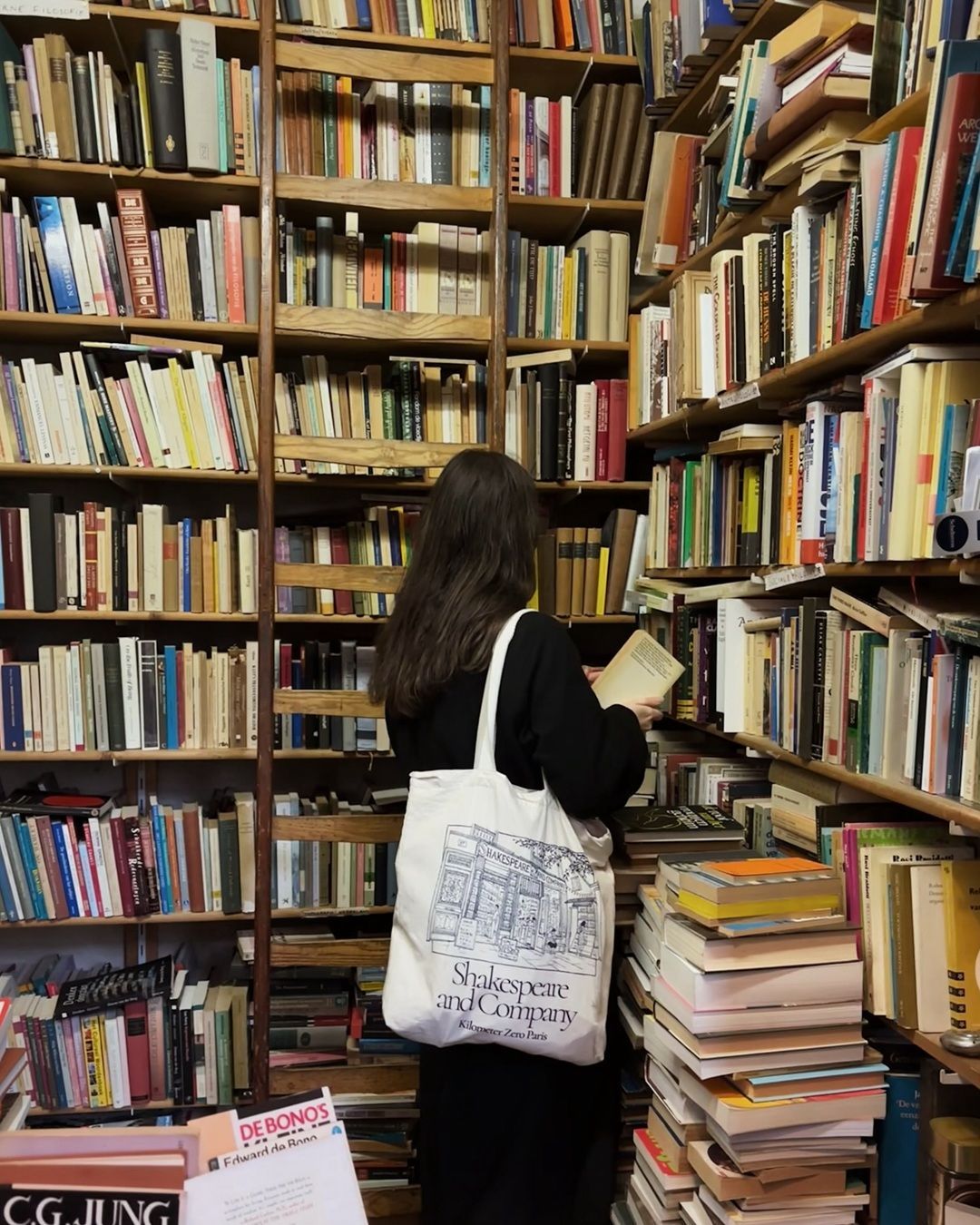

Four books to get through the winter A brief selection of recent reads we may have missed over the past few months, among nostalgia, the Internet, relationships, and identity

Before allowing ourselves a well-deserved, collective Christmas break, we thought it would be worth gathering a short selection of books published in recent months that, due to timing, an overload of new releases, or simple distraction, may have slipped to the margins. These are works that differ in form and origin (novels, hybrid essays, autobiographical writing) but are united by the same urgency: to question who we have become, how we inhabit relationships, work, the Internet, and the passage of time. Four titles to be read slowly, in that suspended period between the end of one year and the beginning of the next, when even questions seem to grow more insistent.

Halle Butler – Banal Nightmare (Neri Pozza)

Not long ago, in a newsletter I follow, I read a Q&A piece asking whether it is right to feel guilty about choosing to become a stay-at-home mom after having a child, and about having life aspirations that were different years, even decades, earlier. Whatever our fifteen-year-old inner selves might think of what we have become, Halle Butler’s novel Banal Nightmare, published in February by Neri Pozza, seems to answer some very specific fears of ours. The protagonist, Moddie, decides to move back to her small hometown after spending her twenties in a big city: drawn by low rent and old acquaintances, she actually finds herself spending her time with cultured and creative people, whatever that may mean, who are selfish, dissatisfied, sly, and slightly sadistic. Butler seems to ask: what might people think whose every social interaction is calculated to obtain power, symbolic or otherwise?

Lily King – The English Teacher (Fazi Editore)

If we were to mark out the months of 2025 according to our readings, The English Teacher would, with some confidence, be the month of December. The best description of Lily King’s novel that I’ve read so far is “nostalgia diluted by ink,” and, as always in the best novels, the plot is simple and spare: a love triangle that begins in college, and life moving on. The novel is divided into two sections corresponding to two different timelines, and the telling of events is entrusted to an unnamed protagonist, nicknamed Jordan, in honor of the character from The Great Gatsby, because “she is no ordinary Daisy.” If you find yourself feeling restless after reading it, pick up Writers & Lovers by King, it might turn out to be a pleasant surprise.

Aiden Arata – You Have a New Memory. Internet and the Perpetual Escape (Mercurio Books)

The author of You Have a New Memory. Internet and the Perpetual Escape (Mercurio Books) has been dubbed the “meme queen of depression.” A micro-celebrity of the Internet, she is known for posting desaturated images of baby animals accompanied by short, sarcastic, self-ironic phrases (“jung would cry if he saw my tiktok feed,” “i must rot to become something new”). In this collection of ten essays, Arata weaves together cultural analysis and autobiography in a fragmented way, much like our online presence. By examining the relationship between identity, power, and self-commodification, and alternating episodes from her work as an influencer with ecclesiastical retreats, Aiden Arata highlights how life after the advent of social media has become far more solitary: “The Internet is like a plastic bag: it’s disposable, but it’s also forever. It’s kind of like it’s on that island of waste floating around out there somewhere. And then, when we use the Internet, in a sense we become like that too.”

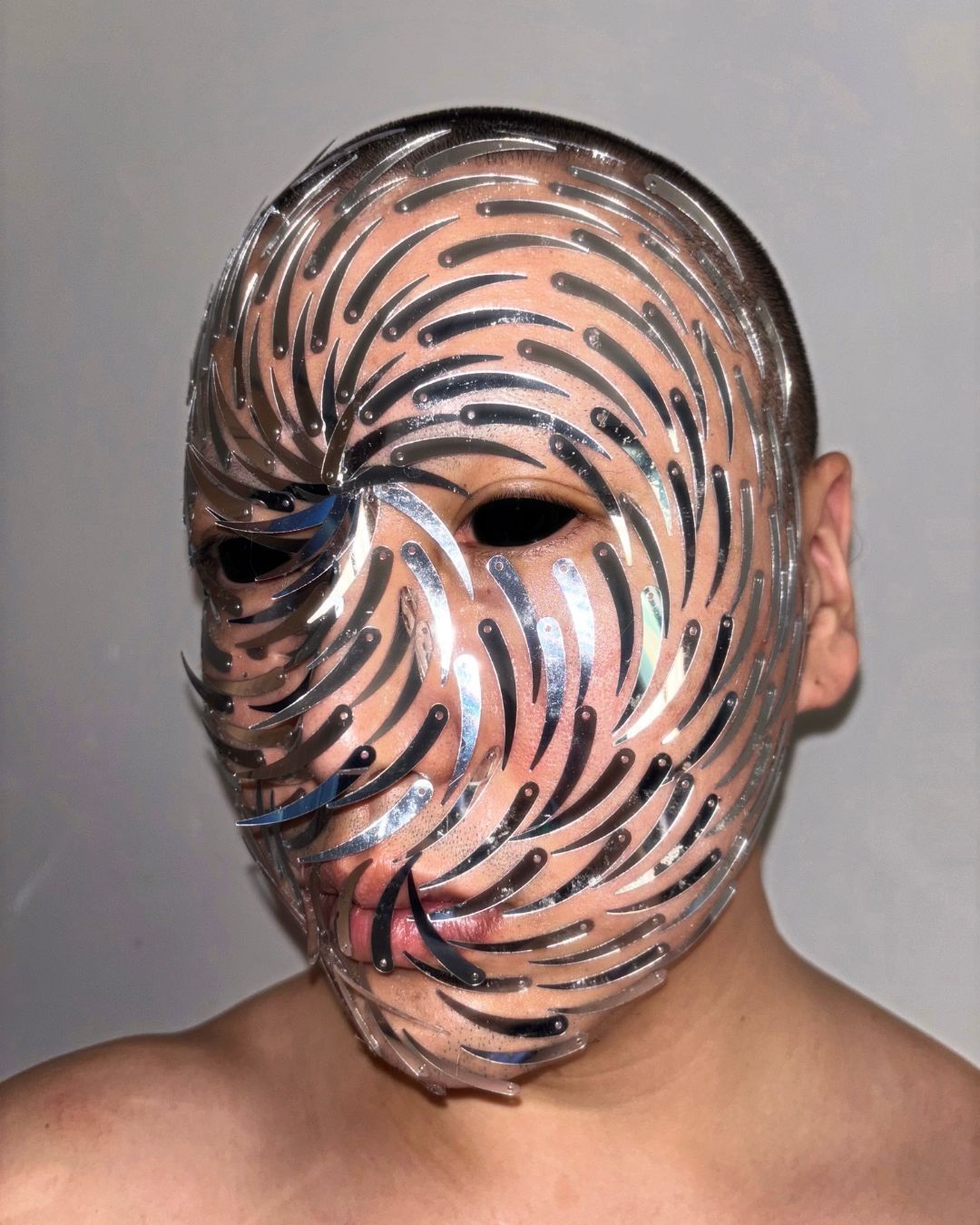

Annie Ernaux – The Use of Photography (L’orma Editore)

Just over twenty years ago, in 2003, the French writer Annie Ernaux experienced, in no particular order, breast cancer and a relationship with a man much younger than herself. Ernaux decided to document this period of her life, a suspended time in which her body hovered between life and death, through photographs accompanied by texts written both by her and by her partner at the time, Marc Marie. The two lovers chose to enter into a pact, spontaneously and naturally: neither would read the other’s text until the experiment was complete, and both would have to write about the same image. The writing between the two proceeds in parallel, and each addresses the other only through an initial, thus completing the distance born of solitary writing, at times even arriving at the use of the same words and expressions. From the experiment, fourteen photographs are selected, transforming the everyday gestures of a relationship into narrative material: clothes hastily thrown on the floor and rooms lit by light present themselves to the reader/viewer “as if they were sacred ornaments.”