In Wuthering Heights, Emerald Fennell did not invent anything She "just" removed something, let's say

The heart wants what it wants. No, I’m not talking about the burning, destructive love that runs between Catherine Earnshaw, the lively and mercurial daughter of a ruined drunk living in the English countryside, and Heathcliff, an unfortunate boy adopted by the family and treated - practically - as a slave, in the novel Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë. I’m talking about what I feel for Emerald Fennell. The controversial director (and an even more controversial screenwriter) has adapted this classic of British and world literature into a film starring Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi, arriving in Italian cinemas on February 12, distributed by Warner Bros. Pictures, just in time for Valentine’s Day, Galentine’s Day, or even Singles’ Day. Take your pick. Now that we’ve set the scene, let’s take a deep breath and begin.

The controversies surrounding Emerald Fennell’s Wuthering Heights

We would need a two-and-a-half-hour roundtable just to list all the major and minor controversies that have followed the film from its announcement almost up to its international release. The first - and strongest - concerned the casting. In the novel, Heathcliff is described on several occasions as a child and later a man with very dark skin, a withdrawn and angry character who, precisely because of these physical traits - and therefore because of racial prejudice - is treated violently, like a servant or even a dog. All of this is neutralized in the screen adaptation, which chooses to give the male lead the face of Jacob Elordi, who is white and conventionally attractive.

Margot Robbie’s costumes and the director’s statements

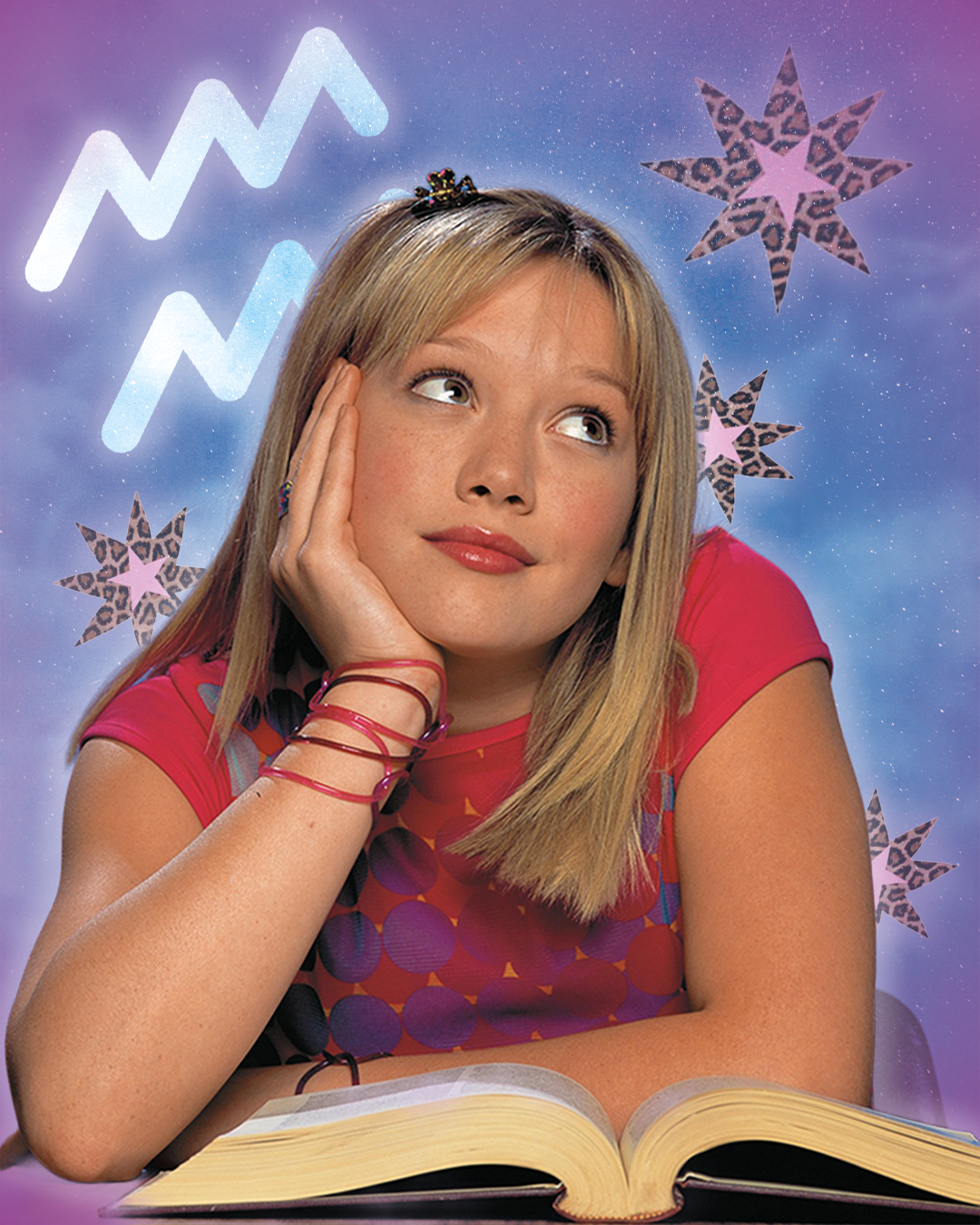

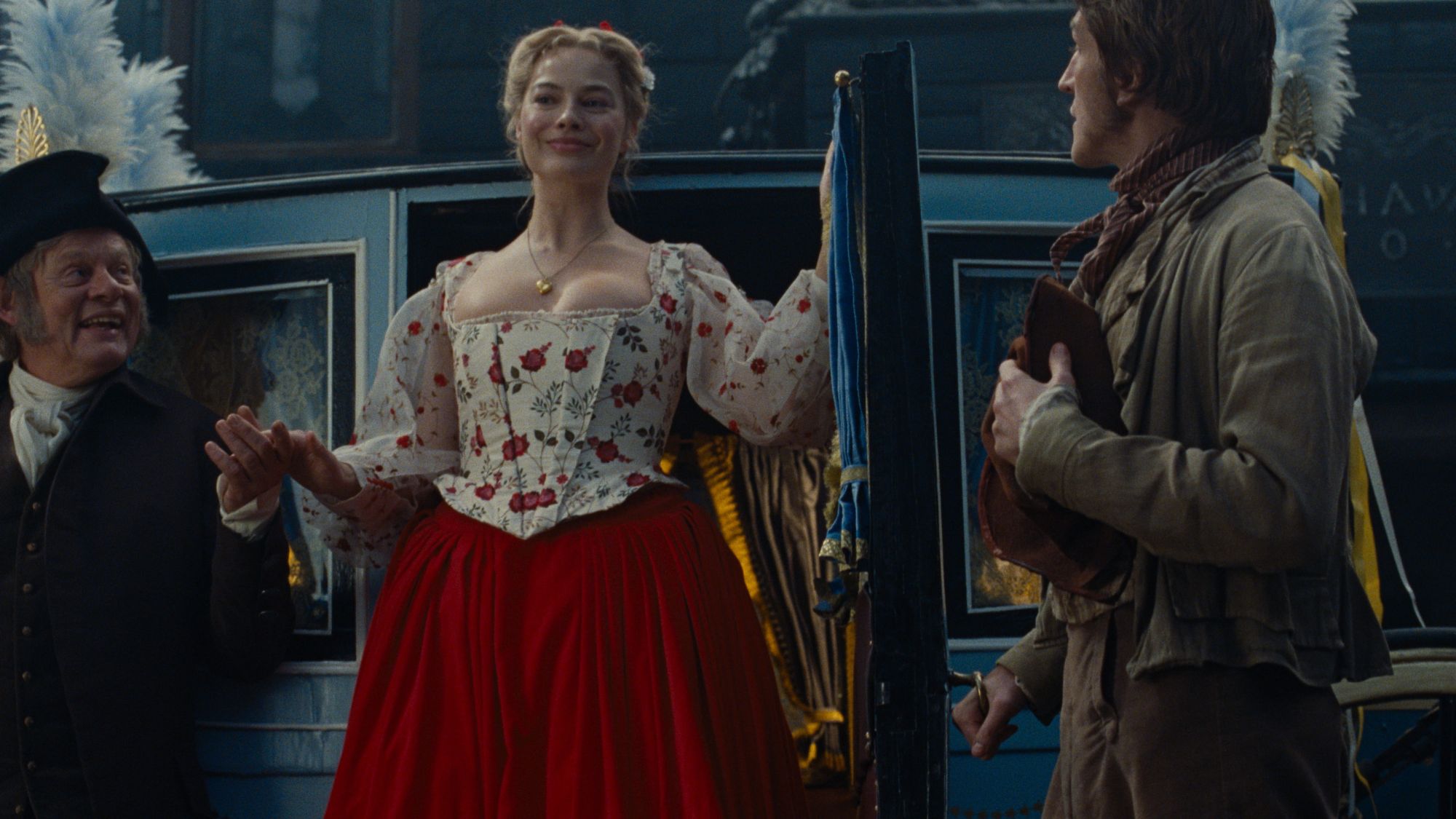

Another major controversy concerns the costumes, makeup, and hair styling. From the trailer alone, it’s clear that the looks - particularly Catherine’s - are anything but historically accurate to what one might have found on the English moors in the 1800s. Is that a problem? For some people no, for others absolutely yes. Finally, adding more fuel to the fire was the director herself, who stated: “I wanted to create something that would provoke the same feeling I had when I first read it - that is, an emotional response to something. It’s a primal, instinctive, sensual reaction.” Critics therefore ask: if Wuthering Heights was originally received with astonishment and controversy for its concentric narrative structure, its social themes, and its raw, unflinching portrayal of the horror within the human soul, why take this book only to turn it into a teenager’s fever dream? Why not write something original instead of stripping down a complex novel? These fears are, in part, confirmed. That said, this doesn’t mean it isn’t a compelling cinematic experience.

So, what is this film like? A review of Wuthering Heights

The truth is that Fennell is a gifted director and a less accomplished screenwriter. She clearly enjoys recreating maximalist, eclectic settings, dressing her actress in beautiful but historically nonsensical costumes, and she has a sharp, effective eye for image, color, and composition. But she has also decided - one might say quite consciously - to remove anything that stood between her and her vision: precise but not faithful, striking like a two-and-a-half-hour music video, kitsch and excessive, an acrobatic game of desire and sexual repression. One thing, however, must be said: she hasn’t added anything. She has simply (and that is precisely the limitation) carefully selected the parts that interested her and discarded the rest. She discarded the concentric narrative structure, and she discarded much of the context. And if some scenes feel cringe, it may be because they’ve been lifted out of that context, not because certain lines sound exaggerated or archaic, or because the protagonists are tormented to the point of pantomime. Those elements, almost word for word, were already in the novel. The back-and-forth taken one step too far, the exaggerated, gothic declarations of otherworldly love. That’s all Emily Brontë, baby.