They want us silent, even in movies From Pocahontas to Mulan, heroines are always portrayed through male voices

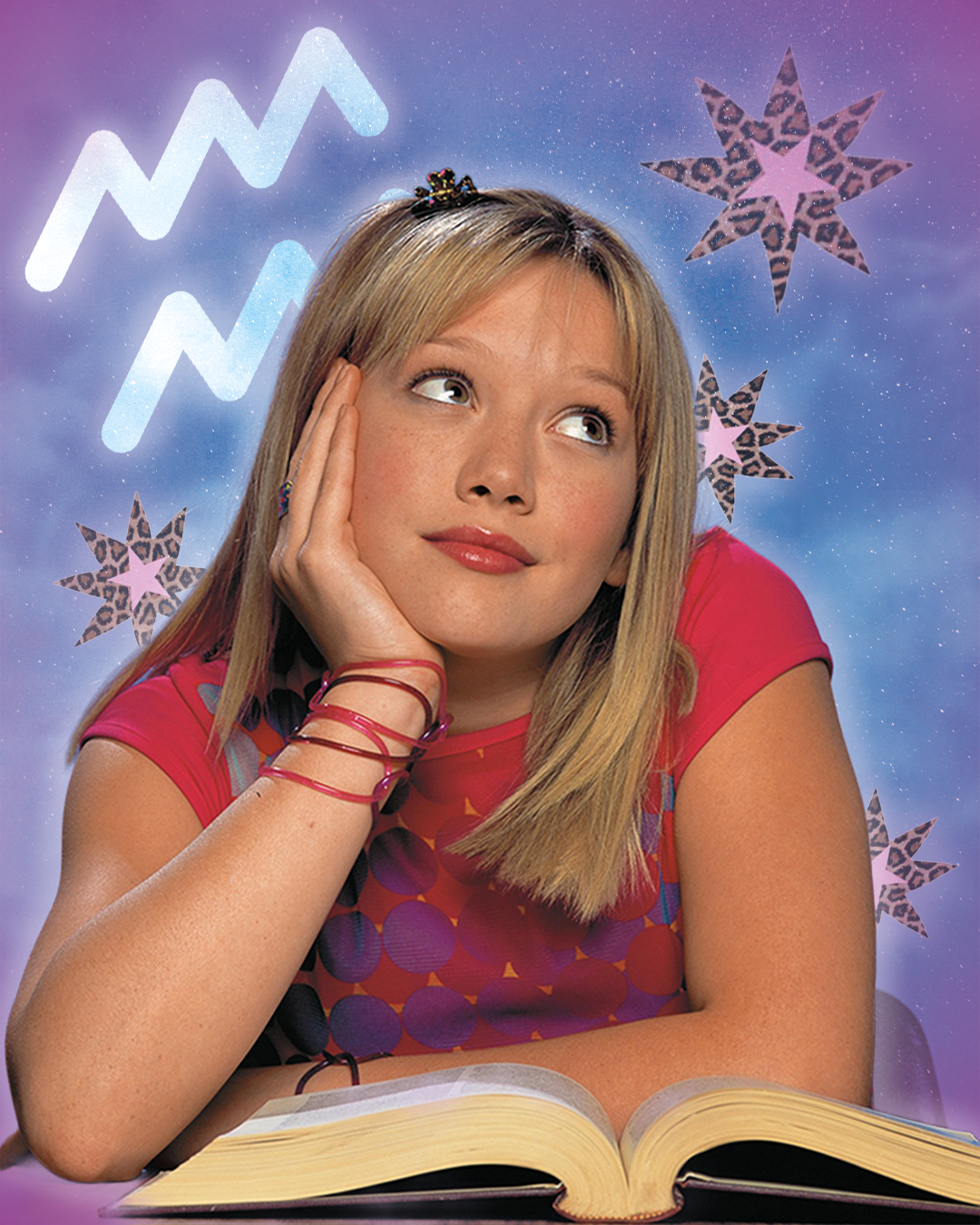

Pocahontas tells the story, obviously fictionalized, of a real-life heroine, a woman who fought for the survival and rights of her people. Yet even in the film that Disney dedicated to her and that bears her name, female characters speak only 35% of the lines, compared to 65% spoken by male characters. It's about a woman who is always told by men. The same fate befell Mulan and many other female protagonists. But this is not just a Disney or animated film issue. It is a structural problem across all cinema, regardless of genre or target audience. In 2016 The Pudding analyzed hundreds of Hollywood films and highlighted something that has, in fact, always been obvious. Even when women are the protagonists, men still speak more.

The male voice in Cinema

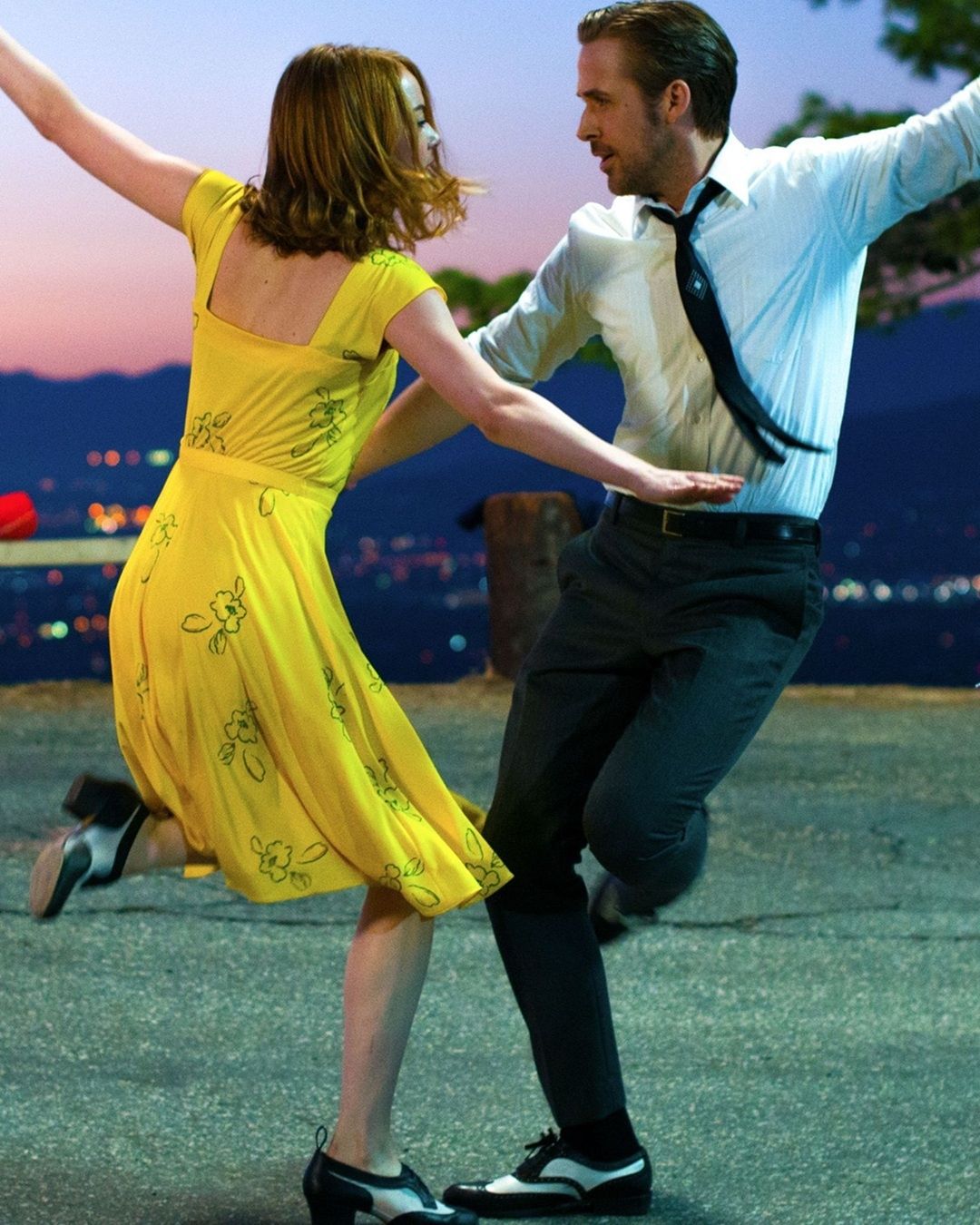

This data reveals at least two key aspects. The first is that, in most stories, it is still the man who drives the narrative forward. The second is that the male voice continues to be considered more authoritative and deserving of space. It’s not just about “screen time”, but about symbolic power. Speaking more means explaining the world and giving meaning to events. In other words, it means guiding the audience’s perspective. There are extreme cases, like Reservoir Dogs, where men speak 100% of the lines. While some analyses exclude characters with fewer than 100 words, the disproportion remains clear. We are not facing isolated exceptions, but a repeating pattern with remarkable consistency. This is also confirmed by the work of the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, which has studied gender representation in films and TV series for years. Their research shows that in mainstream films, male characters speak more than female characters, have more central scenes, and are more often associated with leadership and competence. Women, by contrast, are more frequently depicted as supporting figures, emotional, or serving the development of the male protagonist. In short: mothers, girlfriends, secretaries, shoulder to cry on, subordinate.

Is it getting better? Yes, but only partially

According to the USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative, today 54% of films feature women as protagonists or co-protagonists, an increase from 29% in 2007. This is significant progress, but not enough. Despite greater visual presence, women still speak less and have less influence over the decisions that drive the story forward. This paradox, more presence but less voice, is one of the core issues. Being a protagonist does not automatically grant narrative power. Power, in cinema as in reality, belongs to those who act and control the rhythm of the story.

@gaiasidoni Oggi si parla di inclusività nel Cinema grazie alla satira del Bechdel test 1G: trustnogaiasidoni #cinematok #cosechenonsai Escapism. - RAYE & 070 Shake

How can this situation be corrected?

One of the most cited tools is the Bechdel Test, created by Alison Bechdel, which sets three minimal criteria: the presence of at least two women, who talk to each other, about something other than a man. The fact that many films don’t even meet this minimum says a lot about the state of female representation in cinema. It should be noted, however, that the Bechdel Test measures only presence, not the quality or power of female characters. A film can pass it and still depict marginal, stereotyped women with no real agency. As mentioned, narrative power belongs to those who speak more and make the decisions that advance the plot. More recent studies, such as those conducted by linguist Elizabeth Stokoe and other media language researchers, show how dialogue disparity reinforces the perception of the male voice as “neutral” and universal, while the female voice is seen as secondary or accessory. As long as we continue to tell stories in which women are present but silent, visible but not central, cinema will only reflect and legitimize a hierarchy we know all too well even off-screen. Being represented is not enough; women need to be able to speak and, above all, be heard.