What is the real problem with performative males? As they say online, «my culture is not your costume»

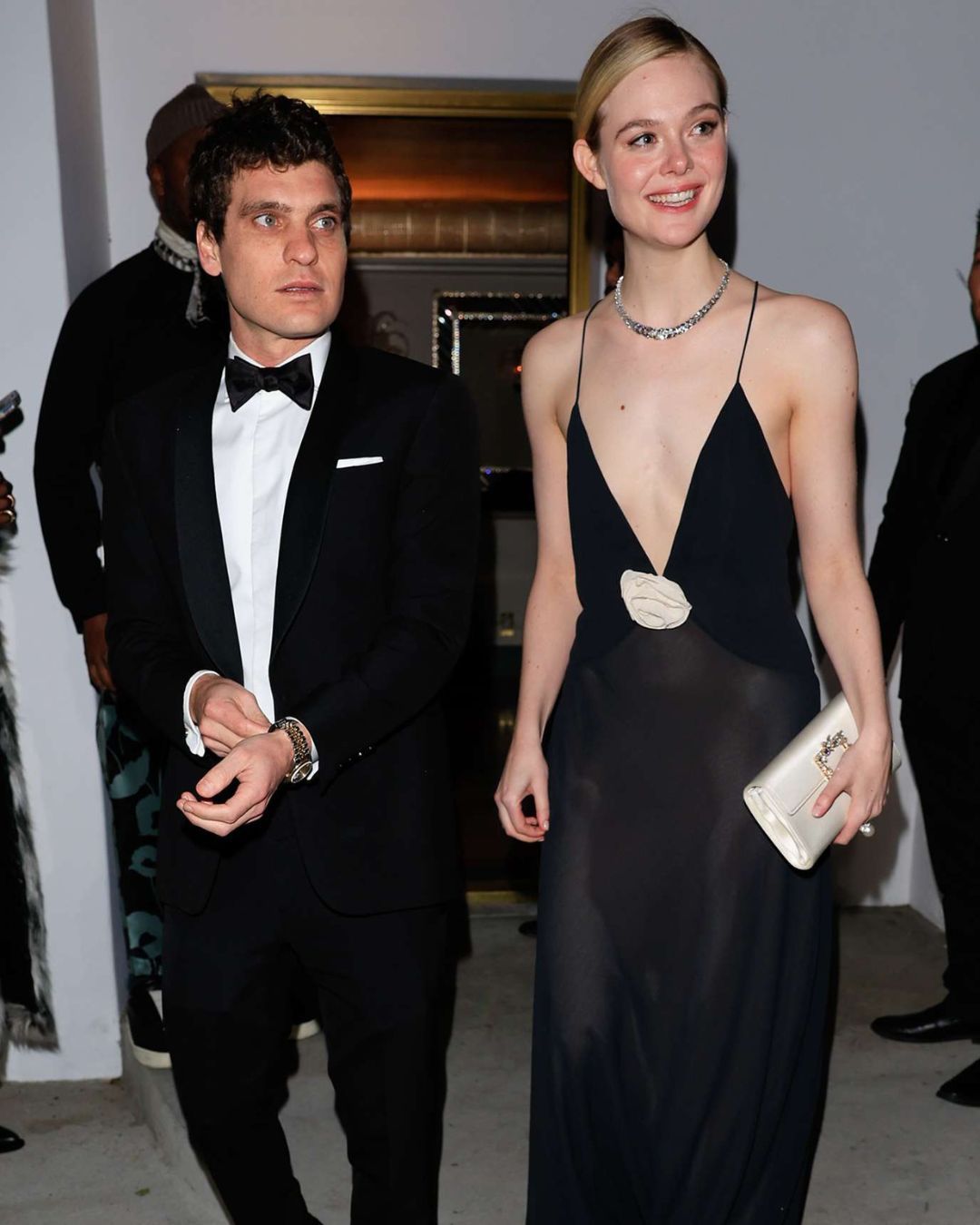

A few days ago, I posted a story on my close friends, hoping my 81 most trusted followers would understand my exasperation: “I would have been the perfect performative male.” It wasn’t just a joke, but the reflection of a conversation that has been everywhere on social media in recent weeks. The term "performative male" has, in fact, become one of this summer’s buzzwords, especially on TikTok, and it points to a new male archetype that has spread online through memes, public contests, and endless imitations. In reality, there isn’t much to explain, since the hallmarks of this figure overlap with habits and codes that have been part of the lives of thousands of women, queer and not, for years. Listening to Clairo, drinking matcha, carrying decorated tote bags, keeping a book in your bag: details that for a long time were read as signs, or rather stereotypes, of presumed bisexuality. Today, however, they have become the most recognizable markers of this new male identity. It wouldn’t be the first transformation we’ve witnessed. First, there were the skater boys, obsessed with Odd Future with long hair and Vans caps, then the male manipulators with mustaches and vintage tees, eager to lecture you on indie cinema or ’90s rock, convinced no one could ever come close to the greatness of Radiohead. In all these versions, the game of manipulation remained confined to a male universe, performances aimed at a similar audience, and only over time were those traits reframed as attractive to the opposite sex as well. This time, though, the dynamic is different. The performative male is born with the explicit goal of appealing to women, of appearing gentle and reassuring, the very opposite of toxic masculinity that we’ve heard about ad nauseam. But if we are truly moving away from the macho ideal, where exactly is the problem with this new figure?

@thejeanluc “Who run the world” #dating #nyc #funny #comedy #fashiontiktok #matcha #fyp #soho original sound - Jean-Luc

As Vox points out, behind the reassuring veneer of the performative male lies a growing suspicion: «maybe these men are not what they seem», and their tastes and behaviors risk being nothing more than a disguise, yet another spin on archetypes we’ve already seen, from the alpha male to the wannabe weeb. The difference here is that this performance is explicitly directed at the female gaze, built on a soft and pseudo-intellectual aesthetic that promises empathy and progressivism. But as Katy Ho reminds us in her Substack, calling a man “performative” is almost redundant, since «gender has always been a performance.» If for centuries women have had to mold themselves to male desire, today it seems that some men have started to orient themselves toward the female gaze, borrowing interests perceived as feminine to craft a more acceptable image. Still, this new expression didn’t emerge in a social vacuum but within a very specific ecosystem: social media. It is above all TikTok that has given many men unprecedented visibility, allowing them to experiment with looser gender codes and forms of expression that until recently were seen as “too feminine,” even something as simple as a fit check. As sociologist Jordan Foster, quoted by Vox, observes, the app has given men «a historically novel public visibility», turning their ability to play with gender presentation into content that is replicable, shareable, and potentially viral. This is also why the phenomenon has taken hold so quickly: more than a spontaneous revolution, the performative male feeds on a continuous loop of trends and imitations that codify behaviors and make them instantly recognizable. Crop tops, second-hand vinyls, or tampons tucked in a backpack are not just signals of a new sensibility; they are, above all, aesthetic markers that thrive precisely because social media needs clear categories, instantly legible figures, characters who lend themselves to staging.

But the issue is not performance itself, as Judith Butler reminds us. The professor in the 1990s introduced the concept of gender performativity, with their book Gender Trouble. According to Butler, gender is neither a natural fact nor determined at birth, but the result of a series of acts, gestures, and behaviors repeated over time until they appear natural. Walking, dressing, speaking in a certain way, everything we think of as an expression of “masculine” or “feminine” is in reality a performative construction, a set of codes we internalize to meet social expectations. From this perspective, there is nothing wrong with men performing a role different from the traditional one. In fact, performance can open up spaces of freedom, helping to dismantle stereotypes and challenging the very idea of gender identity as something fixed. The problem arises when this performance stops being an authentic expression and becomes a mere imitation. In the case of the performative male, the codes put on display—listening to indie pop by female artists on wired headphones, clipping Labubu charms to jeans, dropping feminist references into their feeds—do not come from lived experience but reproduce gestures and symbols that the queer and female community has long used as identity markers. This is where the aesthetic risks of sliding into appropriation, a polished copy of languages that once carried precise political and cultural meaning but that are now emptied and recycled as fleeting tools of seduction.