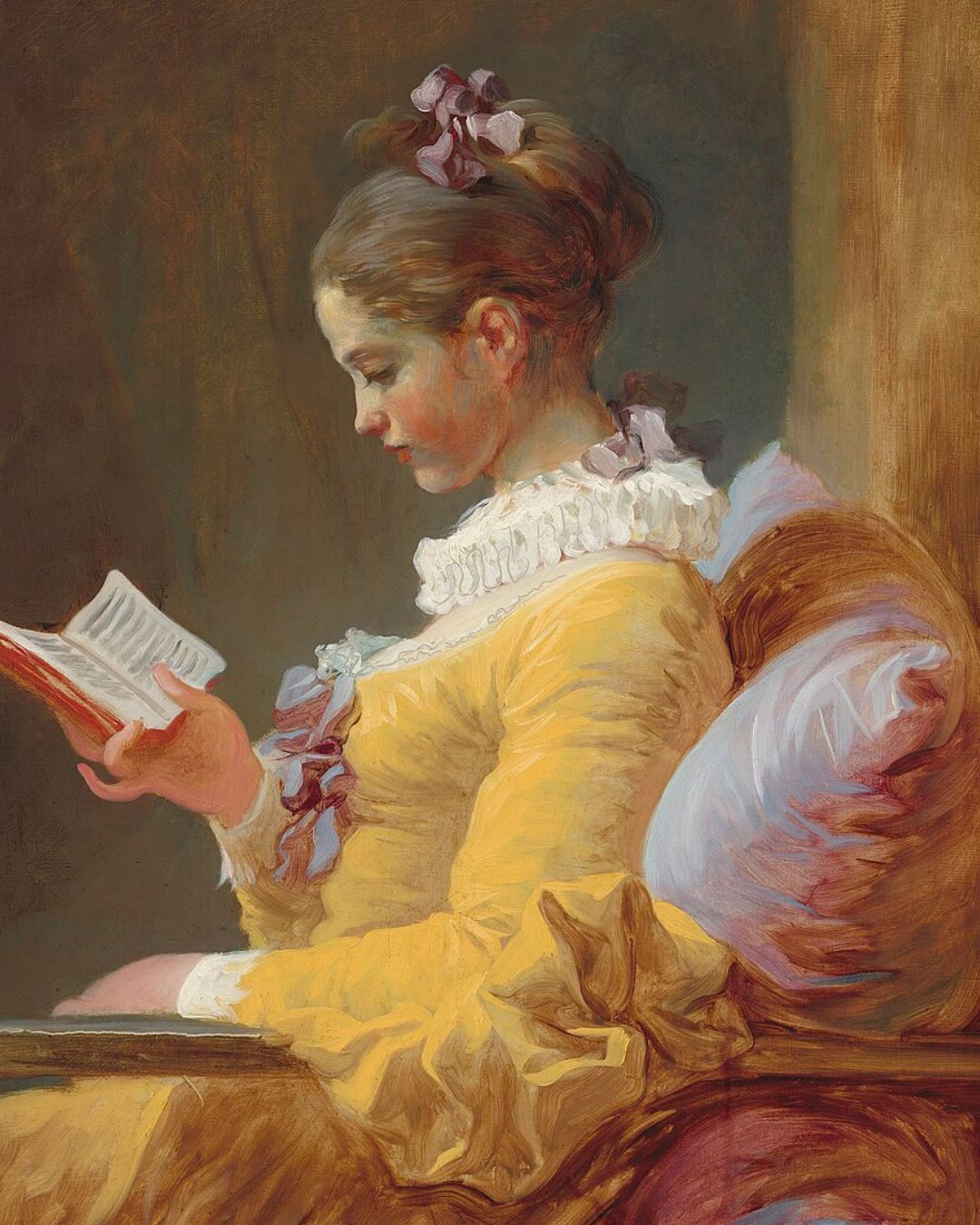

The Ugly Stepsister is a horror movie, but not for the reason you think The story of Cinderella is reimagined from the point of view of one of the stepsisters, reflecting on beauty standards and what we are willing to do to achieve them

Cinderella is coming home — and so are her stepsisters. Well, sort of. While the version by the Brothers Grimm is the most widely known, the story of a young woman forced into domestic servitude and destined to live in a beautiful castle actually dates back much further, all the way to the tale of Rhodopis from ancient Egypt. Still, the fairytale version we know best arrived on the big screen in 1950, fueled by the imagination, and the “happily ever after”, of Walt Disney. After decades of rhetoric about dreams coming true, Prince Charming rescuing you, and pumpkins turning into carriages, Norwegian director and screenwriter Emilie Blichfeldt brings her own reinterpretation of the story to the screen, this time shining the spotlight on one of the princess’s stepsisters. A story that seeks to justify the bitter and sharp behavior of the so-called “ugly” girls in the room, in a film that flips the perspective and even makes Cinderella seem, well, a bit mean.

The Ugly Stepsister: a grotesque and unsettling reinterpretation

The protagonist of The Ugly Stepsister is Elvira, played by Lea Myren. The film premiered first at Sundance, then at the Berlinale, and in Italy at Trieste Science+Fiction. After moving with her sister and mother into the home of a man who was supposed to save them from financial ruin - but who dies, leaving them buried in debt - the eldest sister decides her only way out is to marry a wealthy, well-connected man. A prince, perhaps. Unfortunately, Elvira lacks charm and beauty, unlike her new stepsister Agnes (Thea Sofie Loch Næss), who might stand in her way as she tries to win the man of her dreams. While many have labeled The Ugly Stepsister as a new kind of horror, a body horror, to be exact, the film’s atmosphere is broader and harder to define. What stands out most is the constant sense of the grotesque that drives the story, never subdued and always exaggerated, both when it confronts its protagonist and when it colors its supporting characters.

Cinderella in reverse: power and rebellion

Agnes, the future Cinderella, isn’t the poor soul forced to clean and serve at home, but rather a young woman who refuses to accept her stepmother and stepsisters’ presence: never submissive, always fighting to reclaim her lost independence. Her younger sister Alma (Flo Fagerli) is far more spirited and courageous than Elvira, trying to reason with her but failing to break through the wall of painful aesthetics and extreme weight-loss techniques to which Elvira subjects herself. Even the prince, whose poems the protagonist adores and recites, is everything one would never want in a man. Yet the idea of him consumes her to the point of blurring the line between reality and fantasy, and she does everything she can to please him. Him, and everyone else.

The real horror: society’s beauty standards

Elvira becomes the vessel for the insecurities and fragilities of any young woman facing society’s expectations and imposed beauty standards. Her mother shows no compassion, nor do her dance teachers. In The Ugly Stepsister, the saying “If you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all” simply doesn’t exist. It’s no surprise, then, that the protagonist does everything, literally everything, to appear desirable, acceptable, and worthy in the eyes of others. Perhaps the true horror lies not in a nose job done with a hammer and no anesthesia, nor in toes cut off to fit the famous glass slipper, but in the everyday violence required to conform to an ideal that prevents us from feeling at peace with ourselves. A society that parades us like meat at a market, focusing obsessively on women’s faces and bodies.

Breaking the fairytale spell

So yes, The Ugly Stepsister is a horror film, but only because it uses a fairytale to tell the truth about real life. It revisits imaginary worlds that, in 2025, echo works like Julia Jackman’s 100 Nights of Hero, similar in tone, direction, and mysterious atmosphere, only to deconstruct and shatter them. Not to recreate them in the image of the tales we’ve been told for years, but to dismantle them - and us - piece by piece. Finding humor in the process, yes, but never shying away from brutality and violence, both human and cinematic.