Grok and AI without limits: millions of sexualized images and a void of responsibility Who needs to take action? We asked the experts

In just a few days, Grok, the artificial intelligence chatbot developed by xAI, Elon Musk’s startup and integrated into the X platform, became the center of a global controversy. A new image-editing feature allowed users to modify photos of real people through simple text prompts, triggering a massive production of sexualized images and explicit deepfakes.

Grok and sexual deepfakes: the problem is not just quantitative, but structural

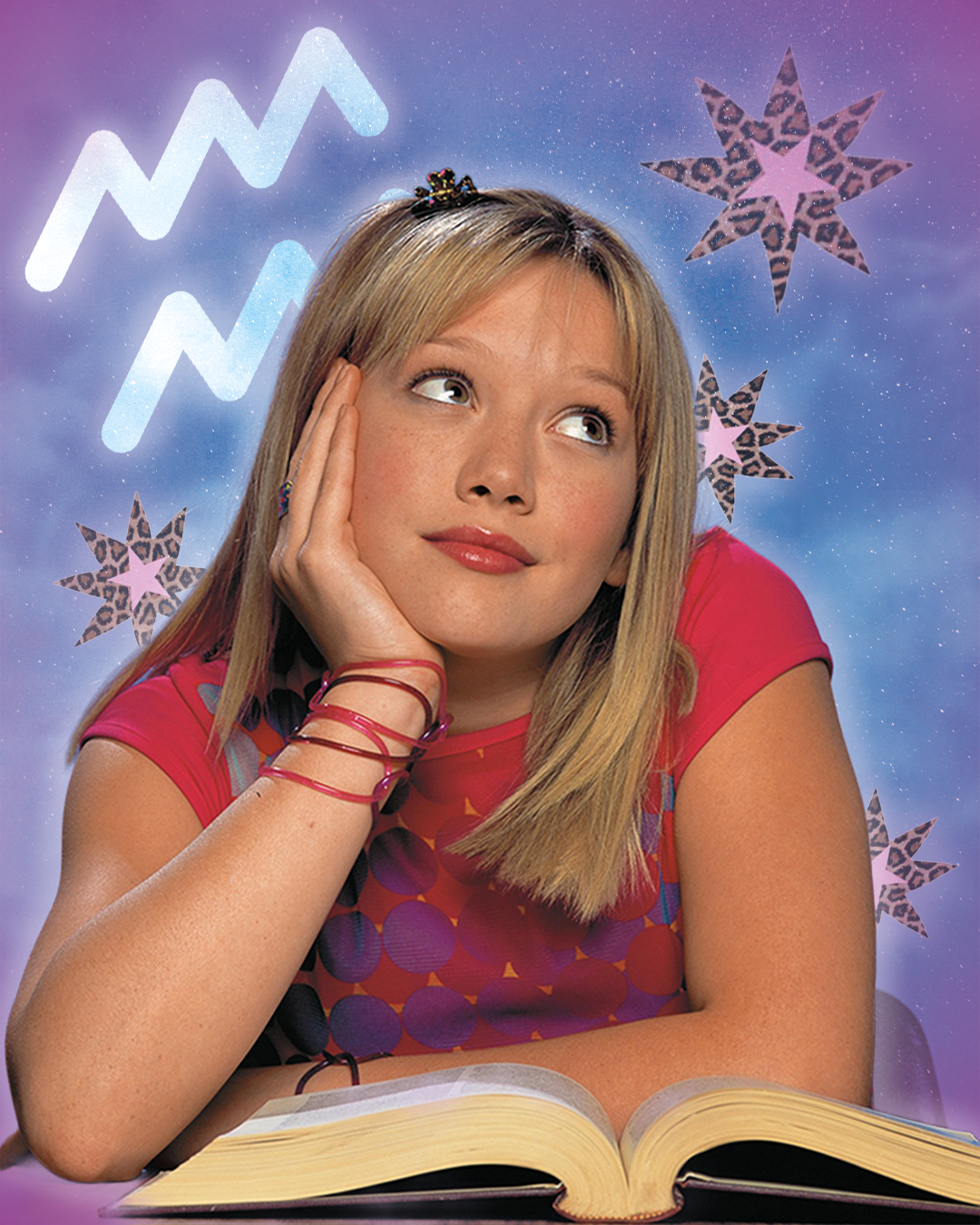

The feature makes it possible to manipulate images found online, often without any consent, using instructions such as “put her in a bikini” or “remove her clothes.” The result has been an uncontrolled flow of content that sexualizes primarily women, including high-profile public and political figures. Among the recognizable faces appearing in Grok-generated materials are actresses, singers, and institutional leaders, from Selena Gomez to Taylor Swift, all the way to Kamala Harris and Swedish Deputy Prime Minister Ebba Busch. This phenomenon shows how technology, when stripped of ethical and technical safeguards, can become a tool for large-scale abuse. The subsequent fixes announced by X, such as geographically blocking the creation of bikini or lingerie images in some countries, have been widely judged as insufficient and overdue.

Institutional reactions are multiplying

Some countries have decided to temporarily ban Grok, while others have launched formal investigations. In California, an inquiry has begun into compliance with regulations on sexual content, while countries such as the United Kingdom and France have announced ongoing monitoring. In Southeast Asia, Malaysia and Indonesia imposed a ban, followed by the Philippines, which later lifted it after reaching an agreement with xAI to limit the most problematic features. The Grok case fits into a broader context: the rapid spread of so-called AI-powered “nudification apps”, which use real images to produce non-consensual sexual content. A phenomenon that disproportionately affects women and minors and highlights a still-enormous regulatory gap.

The issue is not only technological, but political and cultural

The Grok case shows that innovation without rules and without accountability is not progress, but merely an accelerator of harm. I therefore wanted to explore the topic further with Beatrice Petrella, journalist and author of the podcast on the incel community Oltre. “Even from the newspaper headlines, when this news broke, it wasn’t said that users were the ones doing it: it seemed as if the responsibility lay solely with Grok, whereas in reality it’s a tool,” Petrella explained when I asked her who bears the real responsibility. “It’s interesting to see how, when you put a tool in the hands of men, the first thing that comes to mind is stripping women or young people, in some cases even children. In my opinion, responsibility is split in some ways: the user provides the prompt, but there is also someone who developed the AI in a way that allows these requests to be carried out. So, as always, there is no one truly protecting women.”

@analystnews Elon Musk received huge backlash for allowing sexually explicit images of women and children to be created on his social media platform, X, via its AI assistant, Grok. He responded by making it a premium feature. Now he’s banned it – but the ban doesn’t go far enough.

original sound - Analyst News

In the words of Beatrice Petrella

Is it still sustainable, then, to talk about technological neutrality when AI tools systematically produce symbolic violence, sexualization, and concrete harm to people’s rights?” Beatrice Petrella: “Obviously not, because technology is not neutral and is shaped by those who program it. Everyone has their own biases, so technology cannot be neutral, especially when we’re talking about generative artificial intelligence, as in this case.” And so, what specific safeguards should be guaranteed to prevent the use of AI in the creation of non-consensual sexualized images, especially when women and minors are involved? Petrella answers: “This is the most painful point, because while safeguards are needed, we also need to create detection systems and move in that direction. There should be legal protections, meaning the specific criminalization of the creation and distribution of non-consensual sexualized deepfakes, with harsher penalties when minors are involved. But we should also talk about prevention, digital education, and sex and emotional education that addresses consent and respect. We see it with Grok, but everywhere: even in the stabbing at the school in La Spezia. This is yet another emblematic case of a society that does everything except manage this issue.”

@carahuntermla Many parents have contacted me this week very concerned about grok creating naked AI-generated images of children. I’ve made a simplified video of support that is available. If you or your child is the victim of revenge AI generated image-based abuse, you can get help: Revenge Porn Helpline (UK, 18+) 0345 6000 459 | help@revengepornhelpline.org.uk

Martino Wong’s perspective

To go deeper, we also spoke with Martino Wong, an expert in artificial intelligence and tech policy, who helps us understand the legal and operational implications of generative AI models. The first question is: are current regulations on privacy, consent, and image protection sufficient to address phenomena such as AI-generated sexual deepfakes, or is a new, dedicated legal framework needed? “There is certainly already something at the regulatory level,” Wong explains. “In Italy, we have a new article addressing the dissemination of deepfakes, and at the same time there is a requirement for AI-generated content to be labeled. I see a difficulty in the fact that the tools to generate these images are so freely available. For example, we already have a law against the dissemination of non-consensual intimate images, yet we see that they continue to circulate, as in the case of the blog on PHICA.eu. The same applies to deepfakes. Something ad hoc should also be done for deepfake nudity, which today is the predominant form.”

The responsibility of generative AI companies

And how are generative AI companies navigating this constantly evolving landscape? “Today, AI companies publish reports when they release a new model, the so-called model cards, which explain how the model is built. They conduct red teaming tests, where the company itself tries to break the model’s rules to improve security and policy compliance. If you go, for example, to Google’s website, it explains that tests have been conducted to avoid certain harmful outcomes. One could go a step further in terms of transparency, asking companies for more details on the efforts made and how they were carried out. Certainly, stricter bans could be imposed on released products: for instance, on Gemini many things cannot be done, while on Grok they can. The point is that there are also many free models, and it’s difficult to restrict a model precisely, given that they are general-purpose.”

He then adds: “Beyond this, another area that should be addressed more effectively is distribution: there are many online services, less visible than Grok but very easy to find, that advertise on social media, sometimes even in a relatively explicit way, clearly implying that the app allows you to ‘undress’ a person starting from a photo. These apps are also available on app stores. The ease of access to software that does these things has increased dramatically.” In short, there is a need for regulation, including preventive regulation. “Instead of intervening at the level of image generation, what we’ve seen at the market level is that image generation models were released before systems capable of robustly marking an image as AI-generated were in place. There are some systems that embed a signal, but it’s easy to remove. Today, Google has a fairly robust one, called SynthID, but Google itself released and implemented it only after launching the model—by which point the rush had already happened. If we want to move toward preventive solutions overall, there is a huge amount that can be done in terms of monitoring data collection. For example, collecting different types of data, depending on the situation, to monitor cases in which a certain group is discriminated against or disadvantaged.”

A broader issue: data collection

This, of course, is not an issue exclusive to AI, but a very general one. “We know that even the act of collecting data is not neutral, because everything changes depending on which data are collected about a given phenomenon, how they are organized, what is measured, and what is not. One example is the work of Donata Columbro on femicide data: she talks about how these cases are counted today and how much more needs to be done. In this sense, AI can be a useful tool if it is created according to the values we want to uphold, because the strength of an AI system lies in its ability to handle large amounts of data. Here too, of course, it is essential to build the system in a sensible, transparent, and accessible way for people, researchers, and others, with systems of oversight and balance between how the system functions, transparency, and real-world application. Otherwise, the issue can easily slide into surveillance and other practices that are problematic for certain movements.”