When machismo speaks with a female voice And no, catcalling is not a compliment, it's harassment

A few days ago, Anna Falchi, in an interview, surprised the audience with some striking statements about catcalling, describing it in almost flattering terms, as a sign of appreciation that a woman should welcome with gratitude. Words that sparked immediate reactions, not so much because of the person who uttered them, but because of what they represent: a clear example of internalized machismo, meaning those patriarchal beliefs and cultural patterns that many women, especially from older generations, have absorbed to the point of making them their own.

The trap of internalized machismo

Internalized machismo is not a marginal phenomenon. It is one of the most subtle and difficult-to-dismantle consequences of the patriarchy, because it does not manifest through explicit violence but through everyday language, judgments, self-limitations, advice passed down from mother to daughter. It is that voice that says, “don’t complain if they whistle at you, it means you’re beautiful,” or “men are just like that, it’s up to you to adapt.” A voice that often comes from other women, showing how social norms have colonized even the female imagination. In Falchi’s case, her positive reaction to catcalling is not an exception but a window into a way of living and interpreting femininity widespread among a generation raised in the 1980s and 1990s, when the idea of emancipation coexisted with a media narrative that reduced women to bodies to admire, display, and desire. In that cultural context, the male compliment, even the most intrusive, was perceived as legitimization, as confirmation of social value. It is no surprise, then, that those raised in that context may today read catcalling not as harassment but as a gesture of gallantry.

@la.repubblica Anna Falchi, ospite della trasmissione "La volta buona" ha ribadito quel che aveva già espresso in un'intervista: "Il 'catcalling' non mi dà fastidio. Ce ne fossero di uomini che lo fanno, lasciamoli essere rozzi. Ci lamentiamo che non ci siano più i maschi, ma quella è una cosa da maschio". La conduttrice Caterina Balivo replica: "Tu non credi che sia un po' una molestia? Una ragazza cammina, sta al telefono e qualcuno fa un complimento che mette in imbarazzo". E aggiunge "Una cosa è il complimento e una cosa è sessualizzare l'aspetto di quella persona". Questo video è di proprietà Rai

suono originale - la.repubblica

Dangerous words

But if internalized machismo has roots in the past, its effects are still felt today. Because when well-known women visible in the public sphere defend practices like catcalling, they are not merely expressing a personal opinion: they feed a collective imagination that contributes to normalizing forms of verbal harassment. The impact is not neutral: for a young girl listening, these words may sound like an invitation to remain silent, like a delegitimization of her discomfort. The point is not to judge individuals, but to reflect on a cultural mechanism. Internalized machismo works like this: it makes you believe that what you are experiencing is not oppression but courtesy, that the problem is not others’ intrusiveness but your supposed sensitivity. In this sense, it is one of the most powerful weapons of the patriarchy, because it divides women and pushes them to see as a privilege what is, in fact, a form of control.

A present and a future of hope

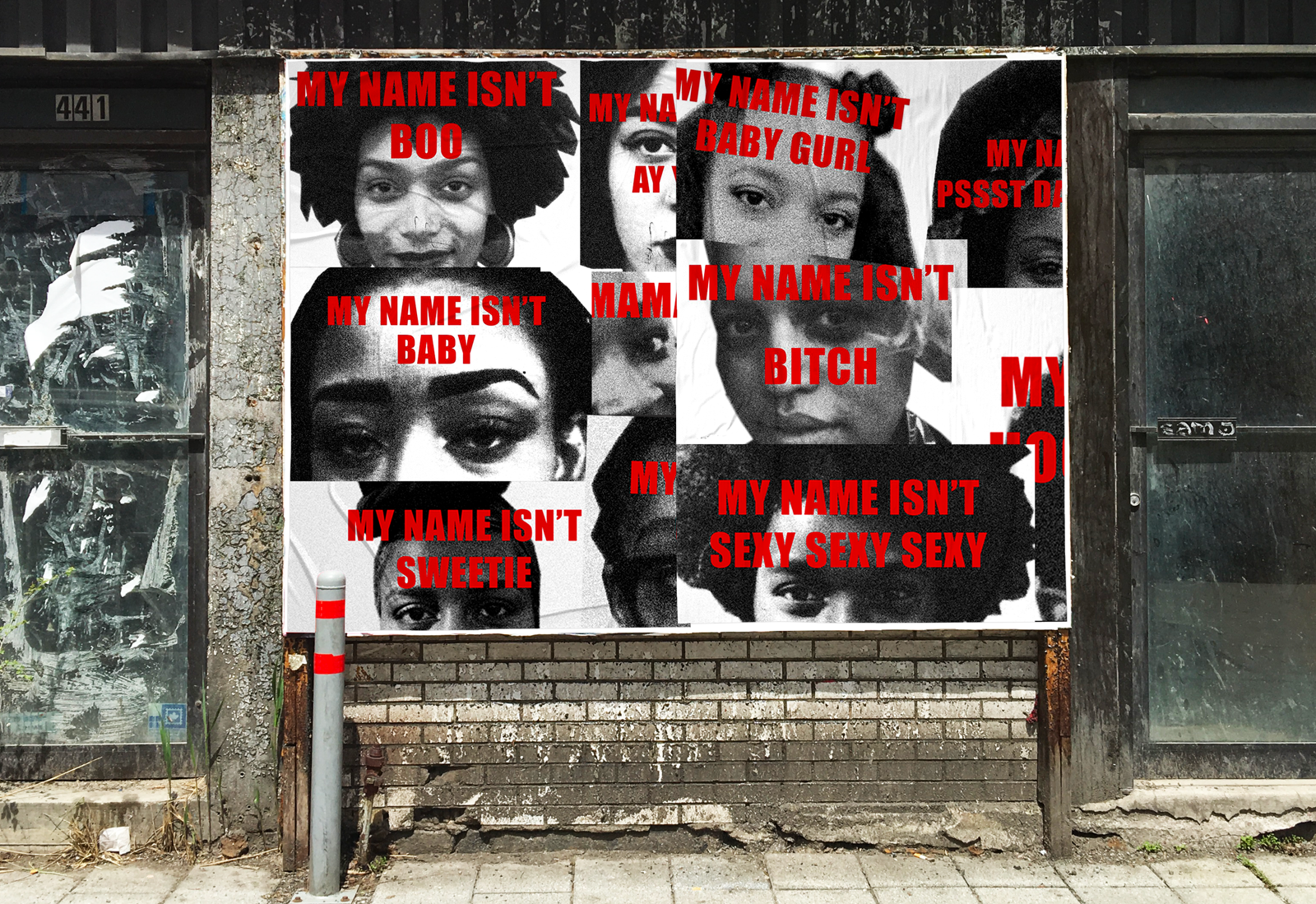

Today, younger generations have different tools to decode these dynamics: feminist campaigns, debates on social media, spaces of collective sharing. Many young women recognize catcalling for what it is: harassment that reduces the female body to public spectacle, an act born not from the desire to “pay a compliment” but from the need to reaffirm power and dominance in urban space. And yet, the generational clash remains evident. Falchi’s words reveal how strong the divide still is between those who consider female freedom as the ability to accept and smile, and those who instead claim it as the right to walk down the street without being interrupted, judged, or commented upon. Internalized machismo is not destiny, but a cultural legacy we can deconstruct. It requires, however, collective and intergenerational work: listening to women who have internalized certain patterns without mocking them, but showing alternatives; giving voice to the experiences of younger women without belittling them; changing media language that still today glorifies the “man who can’t help himself.” Only in this way can we break the cycle and build an idea of femininity that does not need external gazes to be legitimized.

In the end, the Falchi case reminds us of one thing: that the patriarchy does not survive only through laws and institutions, but also through the beliefs of the people who inhabit it. When women begin to say “enough” to these narratives, then the public space finally becomes everyone’s, not just the domain of those who feel entitled to own it.