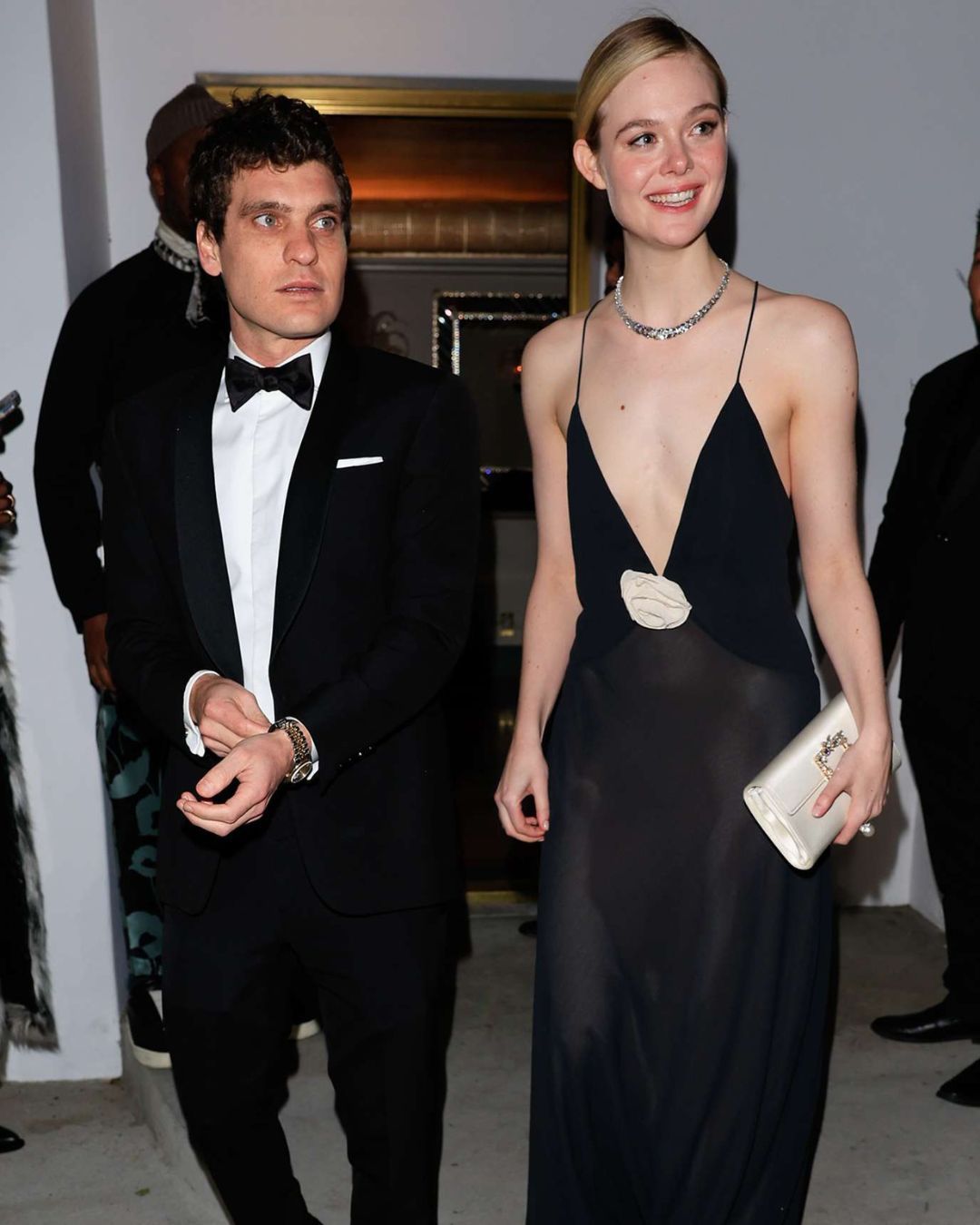

Materialists is like Pride and Prejudice, but in 2025 The new film by Celine Song plays with romantic comedies but does not abandon cynicism

Why does a woman, in 2025, decide to get married? Is it for convenience? For stability or passion? Out of fear or desire? How important is financial compatibility for two people in their 30s or 40s who see marriage more as a contract for old age than a decision made for love? That’s the question Celine Song asks in Material Love (original title Materialists), hitting Italian theaters on September 4. The answers to these questions are many, partial, varied, and personal. They linger in your mind as you leave the cinema after watching a film that doesn’t try to define itself, but does so successfully anyway.

Materialists: plot and cast of Celine Song’s new film

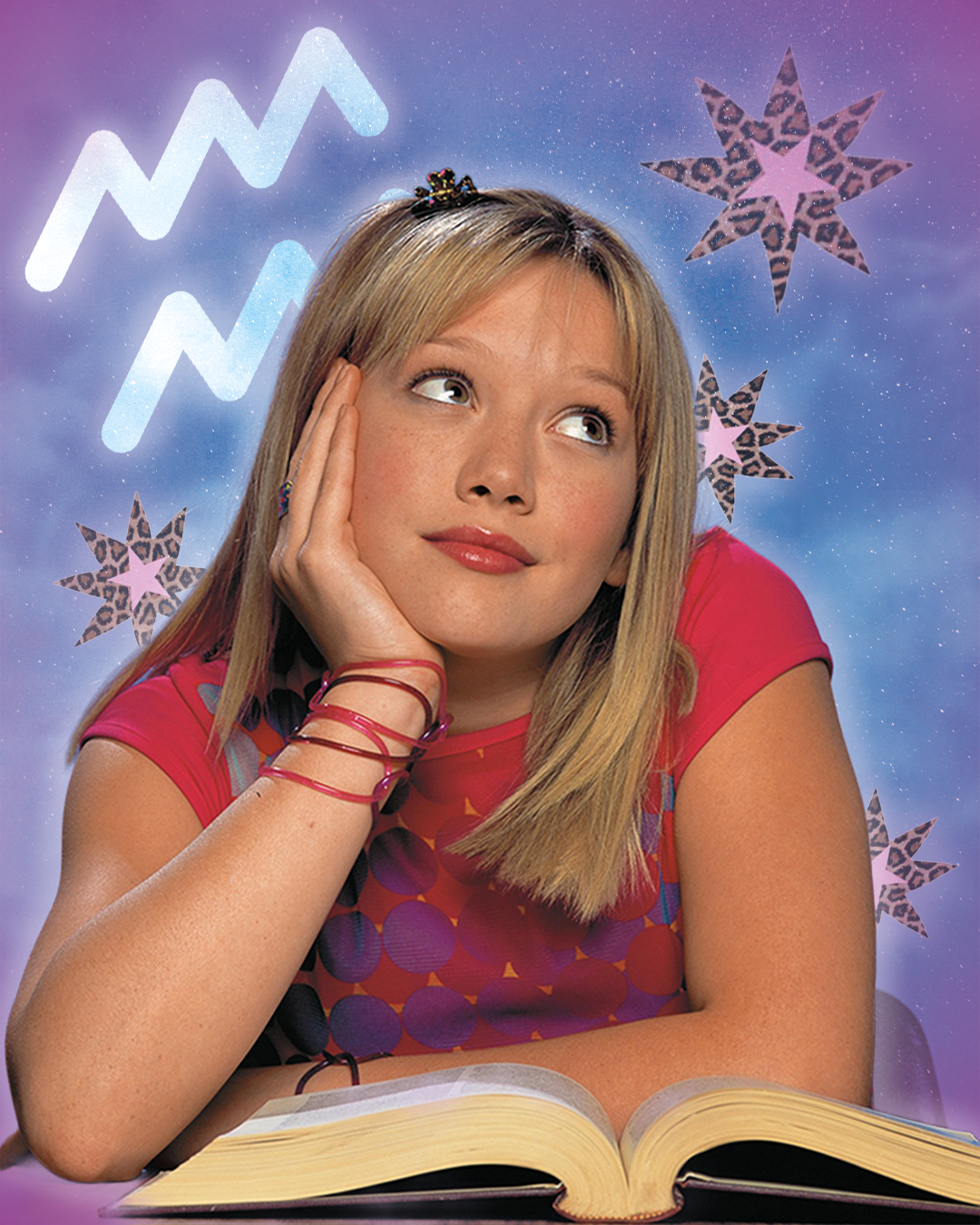

Lucy (Dakota Johnson) is a young woman who’s given up on love, but now arranges it for others. She’s a top matchmaker at a luxury agency that finds the perfect partners (read: husbands) for its wealthy clientele. Life and work have shaped her into a sort of robot of matchmaking. She sees nothing but numbers: salary, height, age. She’s looking (or thinks she’s looking) for the same in her own life: a perfect, wealthy man who can give her the security she’s always longed for and a few fine dinners across New York to make her feel valuable. But when she finds him, she doesn’t believe it. She comes from humble beginnings. The numbers don’t add up. The value feels unbalanced. And so, the triangle begins.

A rom-com tribute that doesn’t shy away from hard truths

Lucy is a modern Lizzie Bennett, only without the luck. A marriage of convenience ultimately doesn’t convince her, and can’t. Her true love, unfortunately, doesn’t turn out to be a grumpy but wealthy Mr. Darcy; instead, he’s terribly broke. Faced with a choice, she picks discomfort for love, in spite of everything she’s claimed throughout the film. This ending, which feels slightly tacked on, reflects Song’s loyalty to the rom-com genre, one she uses and reinvents with a cerebral, dry, cynical twist. It’s almost a required homage, but doesn’t fully align with the worldview presented in the rest of the film, which boldly explores the financial component of marriage and underscores that everyone, in the end, wants something in return from a relationship: a sense of worth, a sense that they’re making a meaningful, socially approved choice. More than that, Material Love is a film that challenges us to admit what we truly want, in the darkest parts of ourselves, from a romantic partnership. Would we accept a controversial leg-lengthening procedure? And what about a partner who can’t afford parking?

The feeling, after watching both this film and Celine Song’s directorial debut Past Lives, is that she’s crafting a sort of cinematic universe of contemporary love, built around various points along the spectrum of romance and cynicism. It’s a semi-serious exploration of what it means to be in a relationship in 2025. If Past Lives began sweetly and ended on a note many read as cynical (though it was really just nuanced and tender, much like real adult relationships), Material Love does the opposite: it starts off with exaggerated, almost caricatured cynicism, in your face, and ends with a conventionally happy ending that feels a bit artificial. What will be the third entry in what we hope is a trilogy? We’ll find out soon, hopefully. In the meantime, it seems the director is set to work on the sequel to My Best Friend’s Wedding.