Sofia Coppola's female gaze The aesthetic codes of a filmmaker turned icon

If it only takes on look to know which director is behind a film, it means that the director in question has created something significant, new and personal, a world of its own in which details and actions differ from film to film, and yet remain magically recognisable. Sofia Coppola's 'female gaze' - as she called it - lingers over pyramids of pastel macarons, rows of satin shoes, a landscape of make-up and perfume that takes a perverse turn in The Bling Ring, telling the story of teenage girls like no other. «It was a kind of worry - she said - teenage films did not respect the audience, their quality was bad. And to shoot teenagers, they always chose 30-year-olds.» In celebration of the birthday of one of contemporary cinema's most eclectic figures, and in anticipation of the release of her new Priscilla Presley biopic, we look back at three films that, in terms of aesthetics and costumes, have set the standard for generations of filmmakers to come.

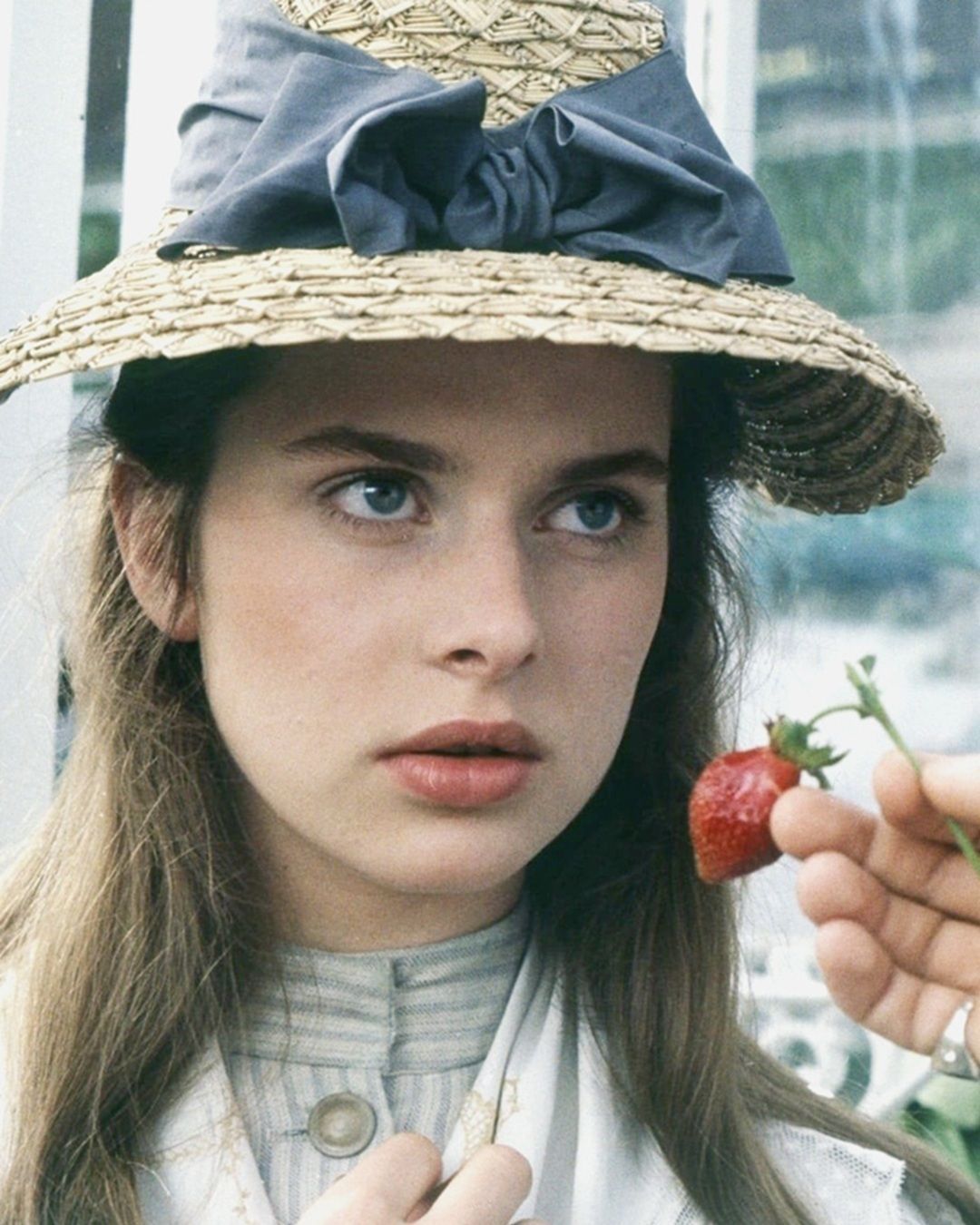

The Virgin Suicides (1999)

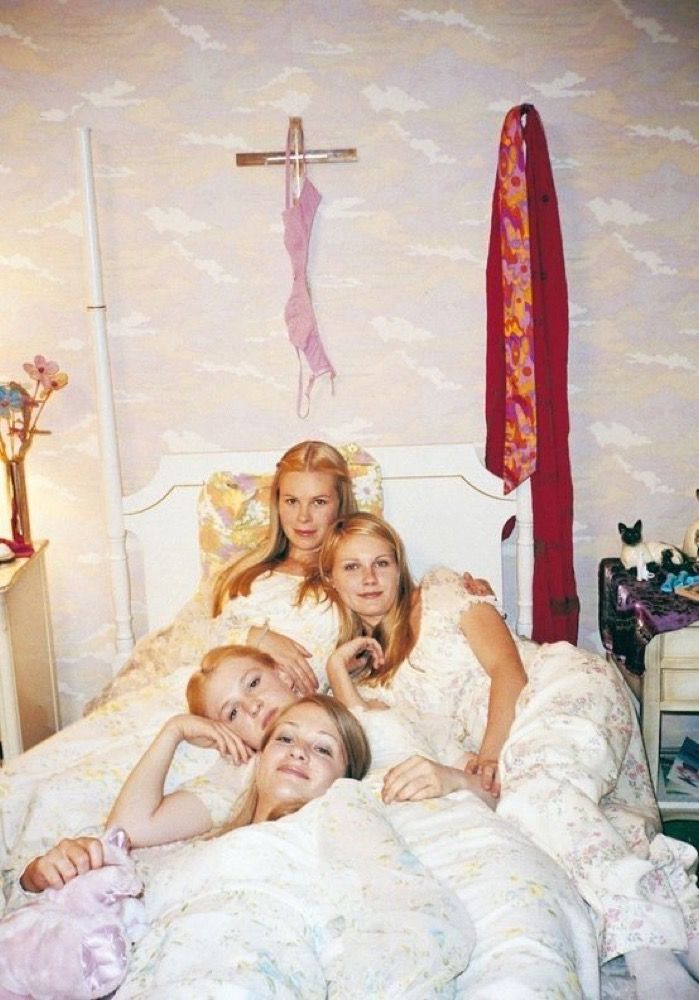

The aesthetic of Virgin Suicides influenced an entire generation of bored teenagers living in a contemporary world where the representation of female sexuality is still neutered and problematic. Coppola worked with costume designer Nancy Steiner to recreate the same authentic childhood of the 1970s amidst virginal lace dresses, bandeau tops and flowered maxi skirts. It's a visual language so evocative that it has a firm place in Rodarte's flamboyant aesthetic and in Coppola's collaborations with her friend and designer Marc Jacobs (the director's Daisy campaigns clearly reference the world of the Lisbon sisters). Just like the objects that characterise the sisters' everyday lives - icons of the Virgin Mary and pink lipsticks - their outfits show the contradictions that made up youth fashion at the time: innocence versus burgeoning sexuality, a pink bra looming over a crucifix. The sense of oppression brought on by strict parental tutelage continues in clothing: in everyday life through the traditionally boxy school uniforms, in the ball scene through the long, bright dresses dotted with imperceptible flowers, reminiscent of the Gunne Sax popular with young girls at the time. A chaste 'prairie house' look that is promptly subdued by Lux's (Kirsten Dunst) gesture when she writes her date's name on the underwear she wears to the party.

Lost in Translation (2003)

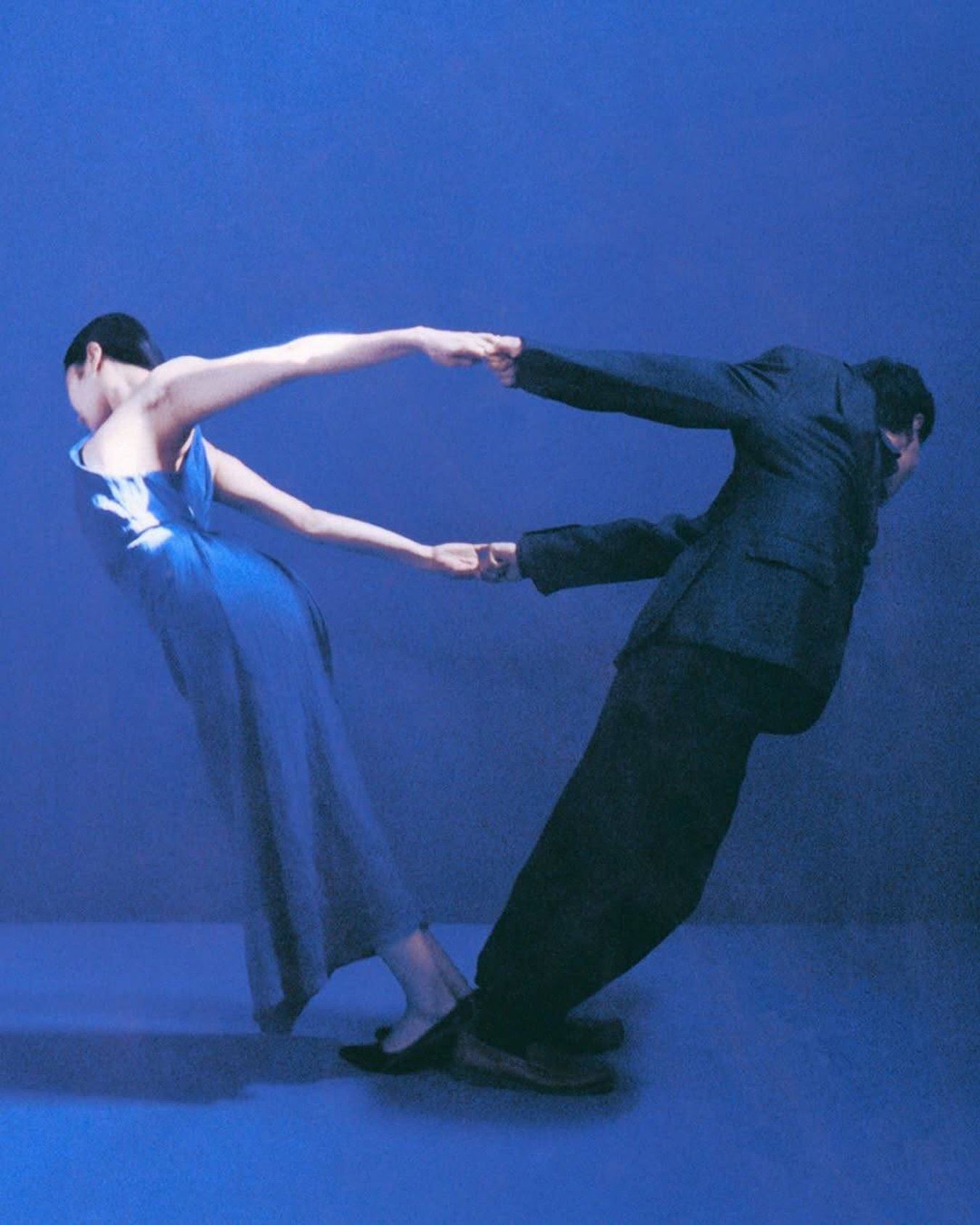

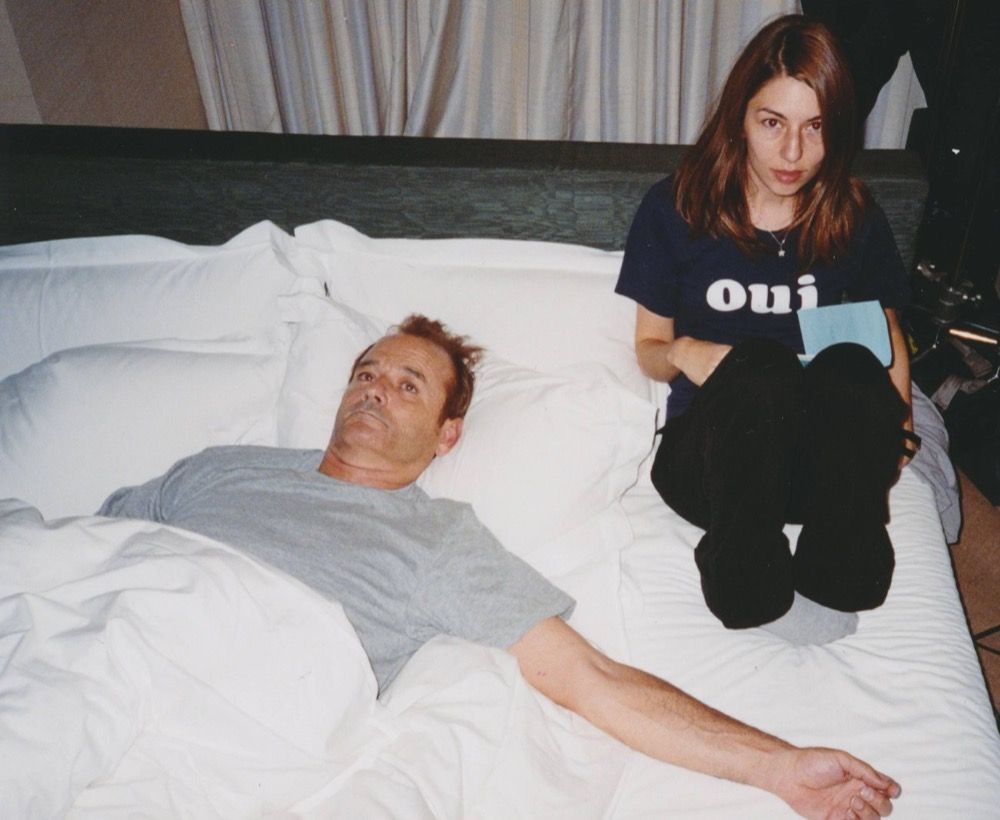

Although in Lost in Translation, unlike other films such as Marie Antoinette, The Bling Ring and The Beguiled, fashion is not central to the narrative of the characters' identity, Suzanne Ferriss points out how the film's costumes reflect the development of Bob and Charlotte's relationship. In the essay, which borrows its title from the award-winning film, the author describes the complexities of filming (27 days without a permit in Tokyo), examining Coppola's allusions to the fine arts, the subtle colour palette and the expressive use of music instead of words. Scarlett Johansson's bottom in a pair of see-through pink panties was chosen for the film's iconic opening scene, a reference to painter John Kacere, who often depicted women in lingerie. In the karaoke scene where Murray sings More Than This by Roxy Music, the actress wears a pastel pink wig anticipating Natalie Portman's outfit in Closer by a year. Charlotte initially forces Bob to wear a reverse orange camouflage shirt to go out. From then on, every outfit is «a sign of their attachment: he allows her to change his look.» Personal items of clothing such as dressing gowns and pyjamas also cement their relationship: when they meet in the gym lift, «they wear the same white towelling bathrobe provided by the hotel. When they sleep together [...] dressed in dark jumpers [...], the parallel outfit impromptu registers their mutual compatibility». The loneliness of the characters stands out against a backdrop of a futuristic Tokyo, yet for the first time in Coppola's work the costumes display a narrative rather than a symbolic role.

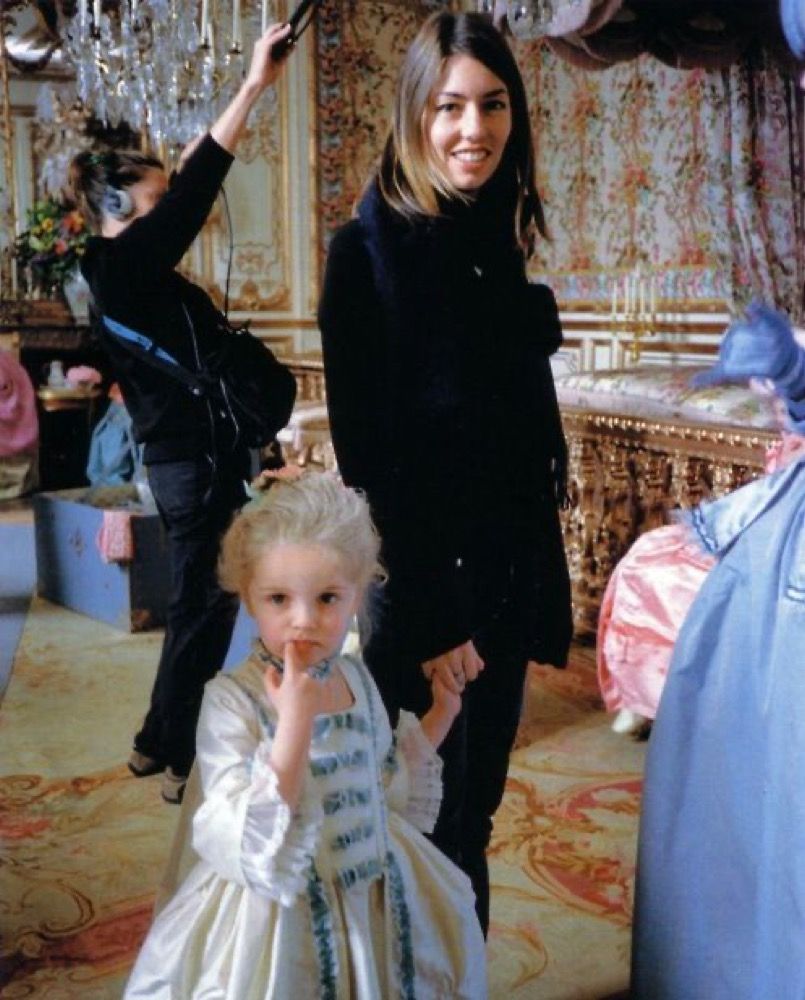

Marie Antoinette (2007)

At the 2007 Oscars, Milena Canonero's costumes for Marie Antoinette won an Oscar because, although not historically faithful to the wardrobe of Louis' XVI queen consort, the sheer splendour and luxury the film costumes exuded made them a representative portrait of Versailles and of the French monarchy at the end of its time. Canonero and six assistants designed the dresses, hats, gowns and costumes for the stage, there were also ten hired workers and the wardrobe department had several drivers for transport, while the wardrobe department worked 24-hour shifts to keep up with production demands. Shoes were supplied by Manolo Blahnik and Pompei, hundreds of wigs and hairstyles were made by Rocchetti & Rocchetti, and there was no shortage of jewellery, with the French house of Fred Leighton exclusively supplying almost $4 million worth of gems. According to the London Times Magazine, Sofia Coppola presented Milena Canonero with a box of crayons at the beginning of pre-production: «she told me: these are the colours I love, so I used them as a palette - said the costume designer - I simplified the very heavy 18th century look. I wanted it to be believable but more stylised». Even today, more than 15 years after its theatrical release, the film proves to be an intimate portrait of the Queen's tragic events, now filling Pinterest boards with a film that perfectly embodies the weight of fashion in decreeing the success of a film's eternal imagery.