From Marissa Cooper to TikTok: eating disorders on the screen The story of a generation in the words of Emmeline Clein

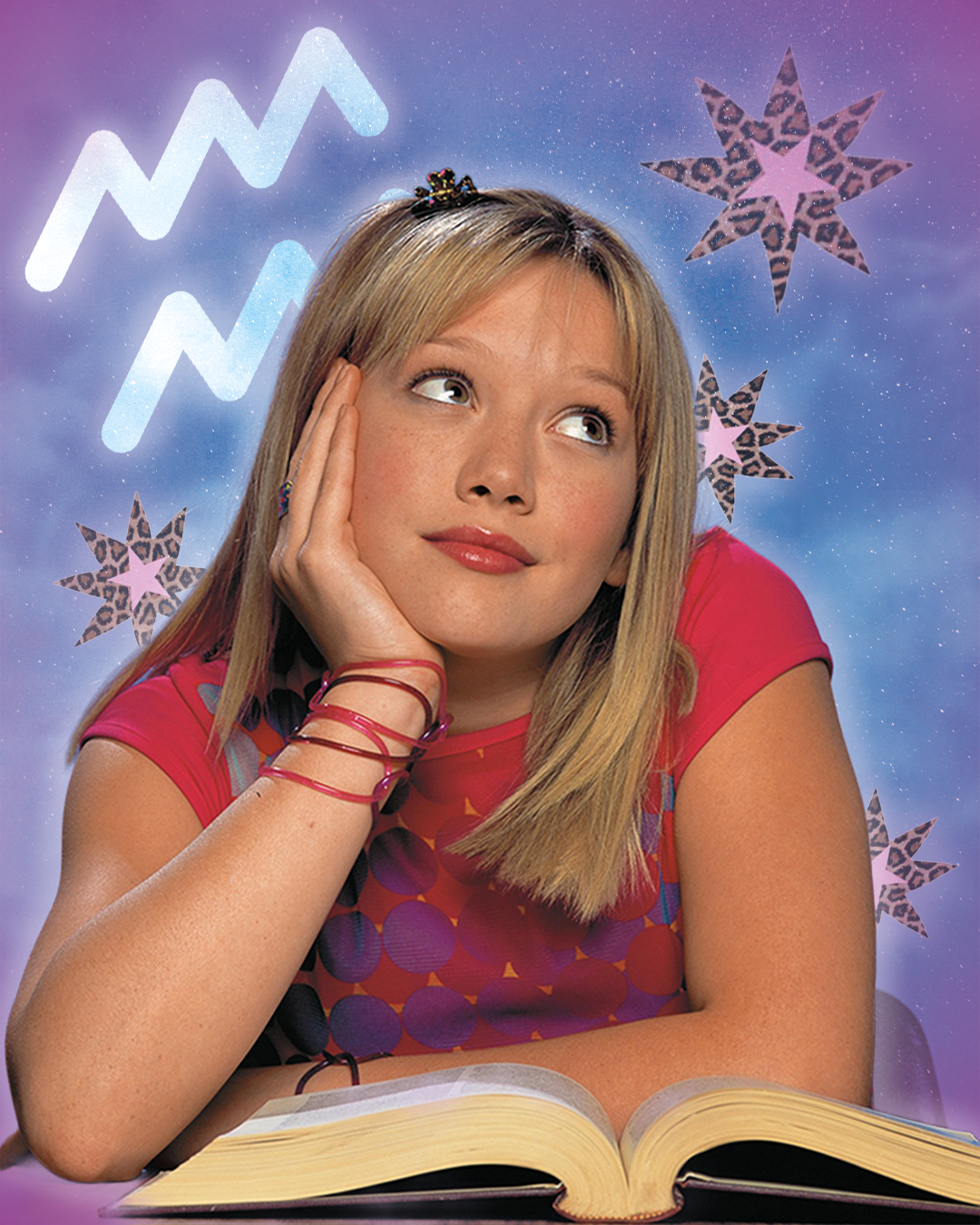

"Have you ever looked at a girl and wanted to possess her? Not like a man would, with fantasies of ownership. Possess her like a girl, or like her ghost [...] inhabit her skin, live her life?" In Emmeline Clein's book, Dead Weigh: Essays on Hunger and Harm (yet to be published in Italy), the author begins by narrating the story of many people, myself included, born in the mid-90s and raised with portrayals of confused and sad girls with eating disorders on screen. Clein chooses Marissa Cooper from The O.C. as the quintessential model ("girls who prefer liquor to food") and gradually shifts her focus to what seems to most unite these sad girls: thinness. She writes about how she found her body to be a tool to express her sadness: by stopping eating and spending endless hours on the computer, scrolling Tumblr, reposting content from other sad girls, their poetry, and black-and-white photos.

Tumblr and Pro-Ana Movements

If we were to compare it to a deceptive scrapbook, Tumblr would be the spine, the structure that allows the rest to exist: blogs where key details like age and weight were listed in the description, photos of thigh gaps—the greater the space, the greater the recognition within the community—gifs of Cassie from Skins, and quotes from Kate Moss (the infamous "Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels"). A community emerged from a platform whose very features enabled such practices: the quick act of reblogging, a single click, and everyone knew which niche community you belonged to, which aesthetic you were drawn to, all through a photo or a phrase taken from who knows where—often falsely attributed.

@bigbooklady That quote can be directly linked to my fear of cheese that lastes four years #tumblr #katemoss #katemoss90s original sound - ༻¨*Dahlia*¨༺

The Role of Media in Eating Disorder Narratives

Communities where the invitation to eating disorders wasn’t hidden—in fact, it was blatant—and that were depicted by the media with alarmist tones, holding the platform responsible for promoting anorexia with aspirational images ("thinspiration") and dangerous practices (sharing guides, tips, and tricks to suppress hunger). All fair points, except that simultaneously, women’s bodies (especially young women’s) were constantly scrutinized by the media and described in tabloids with ruthless and sensationalist headlines that only worsened the situation. By 2012, this phenomenon became gradually less overt: in February of that year, Tumblr’s owners decided to censor content promoting anorexia, bulimia, and self-harm. However, these practices didn’t disappear; they were simply hidden, accessible only to those who already had the specific lexicon to find them online.

@katelynernst4 As requested. Here is what i eat in a day. Listen to your body and fuel it properly. #college #whatieatinaday #wieiad #food #college #meals #healthy sweater weather - user46946067338

Content Promoting Thinness Today: The TikTok Example

Conversely, in 2024, such content is no longer hidden but presents itself directly to users, even to those not actively searching for it. An example? The popular What I Eat in a Day video format: currently, there are nearly 2 million videos of this type on TikTok. A more ambiguous and insidious version of early 2000s magazine pages, where thousands of young creators show what they eat during their days, summer holidays, trips abroad, or at work. The videos typically fall into two categories: one where the food is displayed against neutral backdrops, white or beige, to make it look aesthetically pleasing or to highlight the contents of the plates. The other, where the front-facing camera is omnipresent, and the girl films herself eating, shoveling forks and bites of food into her mouth. Almost always, there’s a body check—a frame where the protagonist shows her body, often very slim. So, what’s real and what’s not? What are we being shown? An enviably fast metabolism or a lie?

@kourtneydiller She will be complaining about drinking that beer too late at night the next day!

Digital Dream Girl

In an interview, Clein uses the term Frankenstasia to define the contemporary aesthetic canon: a kind of beauty ideal shaped by facial filters, Ozempic injections, fillers, and similar surgical practices that mask a form of self-harm. A creature born from extreme diets, surgical interventions, and a reliance on cosmetic treatments. Achieving this aesthetic model doesn’t eliminate traditional pressures around thinness; it amplifies them, integrating them with additional toxic expectations, where, under the false promise of beauty, a series of practices must be performed—in the name of physical and mental well-being. As the author clarifies, recognizing the dangers of these practices and deconstructing the myths that fuel them is the first step toward promoting a culture that prioritizes health and genuine well-being, rather than perpetuating destructive models.