Italian television exploits women's pain Why is a case of lesbophobia treated as if it were prime-time entertainment?

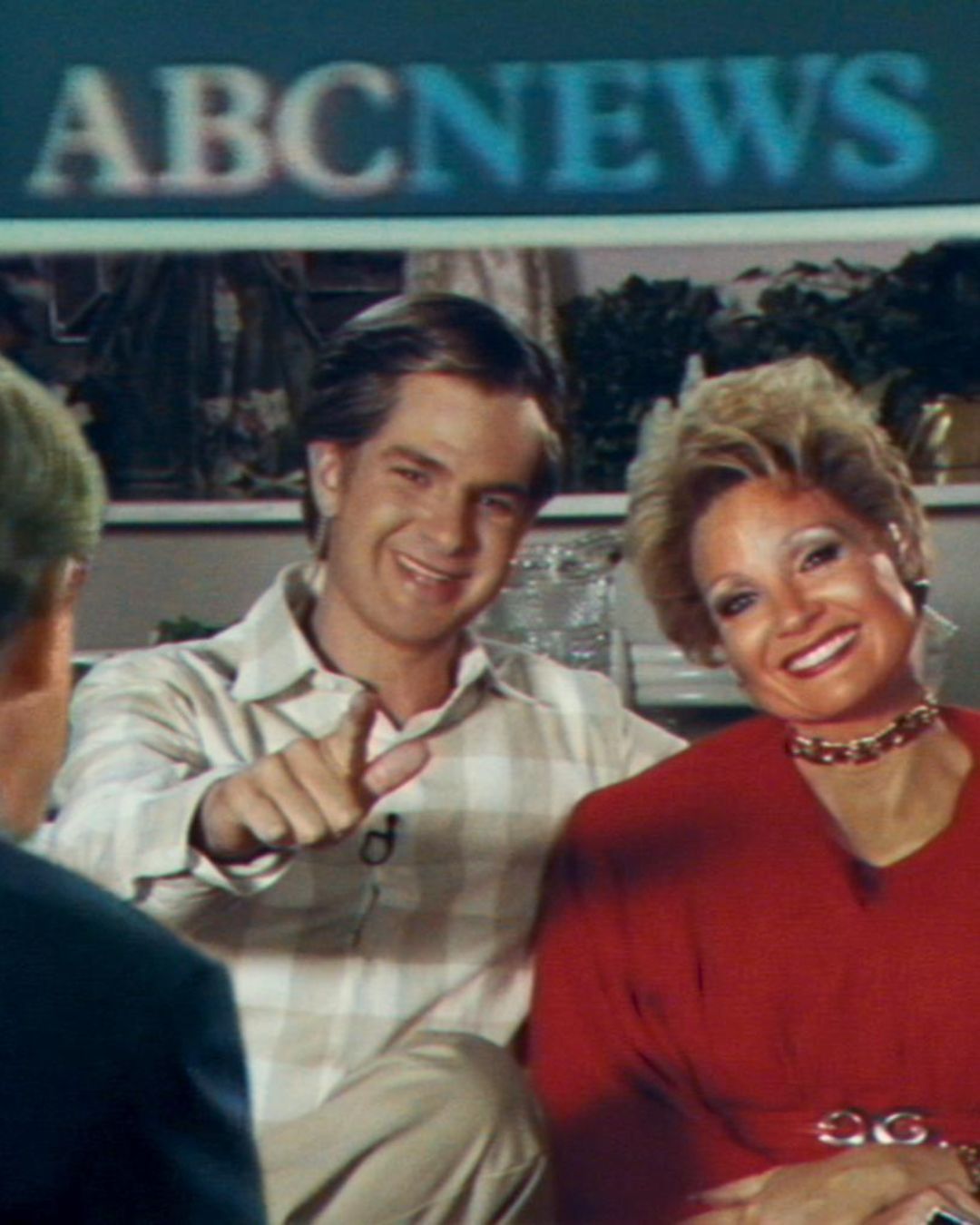

On social media, there's a myth surrounding Maria De Filippi and all her programs and successors. Indeed, in this mythification, there is some truth. The presenter has asserted herself with strength, professionalism, and decisiveness, bringing to the small screen a type of television never seen before, immediately embraced with success and imitability. A cross between a show and reality (which, in itself, has very little reality) that puts human drama in the spotlight, captured in its most emotionally impactful or entertaining moments: the search for true love, family crises and betrayals, the pursuit of fame and the realization of one's dreams. Different from pure reality shows, the MDFCU (Maria De Filippi Cinematic Universe) offers to help its participants. In return, it uses them to keep us glued to the television. We all know: if you're not paying, you're the product. Started, perhaps, as a television format in good faith, it seems to have now degenerated, or maybe it's the audience's tastes that have changed, becoming more aware and therefore less willing to laugh and meme about others' dramas.

C'è posta per te: homophobia on prime time

One episode, in particular, sparked controversy. On Saturday, January 13, C'è posta per te returned to television screens, highly anticipated, as it was followed by over 4 million viewers. One of the cases in the episode particularly touched that portion of users who then chronicle the show in real-time on social networks, effectively sealing its success. A saddened girl calls her family in front of the iconic white envelope in the center of the studio. The family has refused to speak to her since learning about her homosexuality, effectively excluding her from the family unit. In tears, in front of millions of viewers, she pleads with her father and mother to welcome her back into their lives. They refuse. In the end, the envelope opens, but with one condition: that the girlfriend of the main character (who had remained by her side, trying to mediate with great maturity) steps aside, not participating in the reunion. A reunion that, in fact, served no purpose, except to emphasize that family comes before everything, no matter what. Not great.

Television is not reality, but it could shape it

When linguists, in the post-war period, included television among the tools that have most contributed to the spread of the Italian language in a fragmented peninsula, they are telling us something current. The small screen, albeit in disgrace, is still today the only window to the world for many people and therefore profoundly influences them every day. What happens on television is not reality; we don't know what happened in these people's lives before, during, and after the process that leads to their participation in the show, which is just a fragment, a slice of life. Based on that and only that, we form our opinions, and what we know is only what we see: a misguided message of extreme compromise in a moment of weakness for the sake of a happy ending, a way to grip the superficial audience, touching emotional cords and igniting passions without explaining anything afterward. It's the same mechanism, for example, that drives the host of Pomeriggio Cinque, Myrta Merlino, to welcome the testimony of the girl victim of the Palermo case, putting her at the center of a media storm, under the public's microscope. And not everyone has good intentions.

C’è Posta Per Te: Maria De Filippi asfalta l’omofobia con una frase pic.twitter.com/n0cTt0EvEe

— Francesca (@Fr4ncyTUrry) January 20, 2019

An alternative show

We are not here to judge C'è Posta Per Te or its audience. However, the fact that a serious issue like homophobia is used in this way, treated as a skirmish to be resolved in prime time, one of many cases in a sequence of contrasts and conflicts, at the mercy of the Italian public, is a problem. A problem that does not only concern Maria De Filippi but the entire contemporary television - at least from Barbara D'Urso onwards, not to mention Ciao Darwin - that uses people as it pleases, pretends to want to help but then, in that same moment, manages to belittle and exploit, to squeeze and then discard its protagonists like used tissues. In the process, just for bringing these themes to the small screen, it flaunts its progressiveness and its being up to date with the times. But is this really all we can expect from Italian television? Is there really no possibility of a different approach, without envelopes and without tears? A sensitive approach that respects everyone's wishes and does not polarize a delicate issue like lesbophobia, portraying the love of a woman for another woman and the same woman's love for her parents as opposing and openly at war with each other?

Is the real country unsalvageable?

It is the real country, you might say using an italian expression, il paese reale, and it must be represented. There are different ways to raise awareness about a social issue, and that of Italian television is anything but documentary; instead, it is mediated by what the audience wants, an extremely emotional approach, and the very strong presence of the presenter in the studio. Perhaps, then, precisely because the so-called real country is frighteningly lesbophobic, transphobic, and homophobic (as well as misogynistic), the issue should be explored in other ways, less theatrical. Because even the real country can change if we give it the chance instead of continuing to hit it in the gut, appealing to its basest instincts and the outrage of those who, instead, stand on the other side. Read the comments, if you dare.