Italian cinema has a problem with feminism Well before C'è ancora domani

At the beginning, there was Barbie, the summer movie that conquered the world and topped the annual box office charts, saving a usually dull and uninspired summer film season. As with global success, controversies ensued for Greta Gerwig's film, accused of almost everything—being too extreme, not sharp enough, unfair to men, and simultaneously too kind and permissive. Despite the criticisms, the audience largely adored it, and Grammy nominations are already rolling in.

The Cortellesi Case

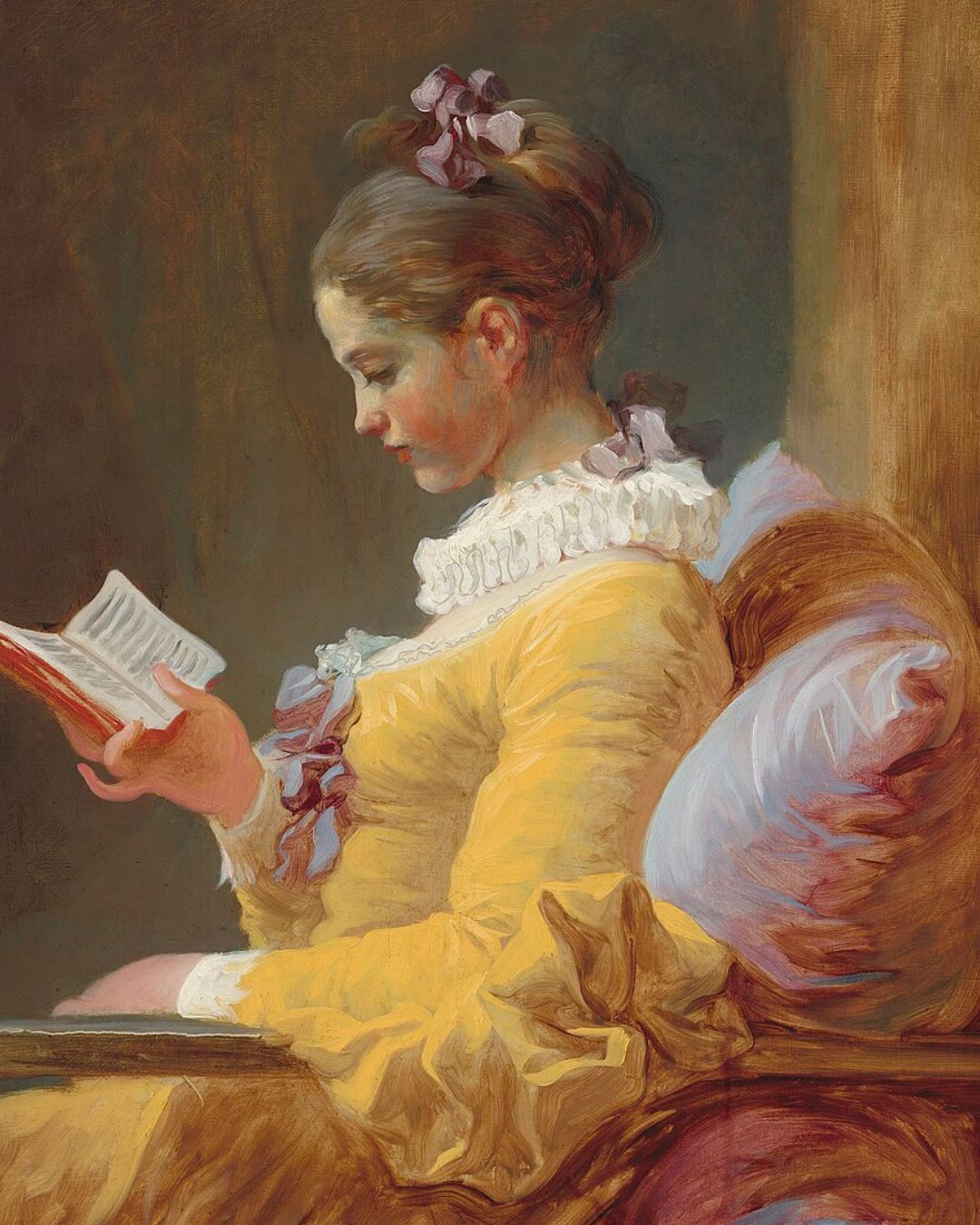

Something similar just happened in Italy, surprising everyone. "C'è ancora domani," Paola Cortellesi's directorial debut, dominates the box office. Despite their apparent differences, the two films share more than meets the eye. Firstly, they are directed by women and tell stories of women (one in plastic) for a female audience. Secondly, they both depict stories of women's empowerment. While Barbie explores the real world, discovering that much of what seemed certain and reassuring was a lie, Delia (played by Paola Cortellesi herself) decides to challenge the established order, what was absolute normality for her and her friends, to undertake the greatest act of defiance: deciding something for herself for the first time in her life.

Italian Criticisms of the Film

In Italy, this didn't sit well with everyone. "C'è ancora domani," despite being a beautiful, positive tale about a hard-won right, filled with references to Italian cinema and offering reflections on class and misogyny, was labeled by some as rhetorical, superficial, simplistic, exaggerated, and overly sweet. In short, something womanly, not worthy of significant consideration.

Annamo bene: un film che dire stucchevole e retorico è fare una gentilezza - con la profondità di Littizzetto -, un altro parafascio ma democratico perchè scritro da Veronesi. Che a scriverlo sia Veltroni non stupisce pic.twitter.com/Msde8TT019

— Bruno Montesano (@brun_montesano) November 11, 2023

Examples of Feminist Films in Italy

The question to ask, perhaps, is: why does such a simple and seemingly obvious film provoke such anger? The answer might be that Italy has a problem with feminism in general and in mainstream cinema in particular. Consider this for a moment: before "C'è ancora domani," which Italian film offered a sensible and evidently uncomfortable reflection on what it meant to be a woman in this country, sparking an inevitable and even more uncomfortable discussion about the present? While comedies are laden with irredeemable stereotypes, the dramatic genre might have something. "Viola di Mare" in 2009, directed da Donatella Maiorca tells a tale of women who love women. Other titles could include "Fortunata" by Sergio Castellitto or "Primo Amore" by Matteo Garrone.

A Problem of Audience and More

In all these titles, however, the focus is on violence and suffering. Moreover, almost all directors and screenwriters are men. Here lies the problem. In an industry where in Italy, you're considered a young promising talent if you're under 50 and where female directors are very few, the issue is fundamental. Empathy is lacking in the audience as well. The male audience, the favorite of Italian cinema, struggles to see themselves in the female characters portrayed by women or perhaps is unwilling to make the leap, to put themselves in the shoes of someone who, on top of everything, is telling them loudly and clearly that it's time to change. Being told that they are powerful and privileged disturbs everyone, especially men: it makes them responsible for things they would rather not be responsible for. The problem is also socio-political. Our first female prime minister is also misogynistic, anti-abortion, pro-traditional family, leaves her partner on Twitter without mentioning the harassment inflicted on a colleague, and shows little interest in femicides unless they are committed by foreign men, preferably non-European.

Se Paola Cortellesi sbanca con un film in bianco e nero su una donna maltrattata, forse qualche domanda su ‘quello che vuole la gente’ sarebbe il caso di farsela.

— Luca Dini (@sonolucadini) November 12, 2023

A Glimpse into the Future

The landscape is bleak, both within the film industry and outside. However, the audience has spoken. If a film like "C'è ancora domani" has excited them so much, perhaps there is hope. Thanks also to those who will come after Paola Cortellesi and the actresses who, courageously, venture into directing, such as Alice Rohrwacher, Micaela Ramazzotti and Susanna Nicchiarelli.