Princess Sissi returns to haunt fans Between myth, reality and a new Netflix series

For years we have been sold her as the quintessential dream princess. Years and years of re-runs of the trilogy of films starring Romy Schneider made in the 1950s have told us of a carefree Princess Sissi who loves animals and the outdoors, wears voluminous pastel puffy dresses and out of love tries to live with strict palace protocol, ruled by good heart, compassion and a hint of watered-down rebellion. Yet the real life of Elisabeth of Bavaria, Empress of Austria, better known as Sissi (or Sisi as she used to sign her name) was far less romantic and glossy than Disney mythology has led us to believe. Now, The Empress, a Netflix mini-series, and Corsage, a film coming in December, try to tell us about her from a new point of view, giving us an alternative and more complex image than the one sculpted in the collective imagination.

On 29 September, The Empress, a mini-series directed by Katrin Gebbe and Florian Cossen, made its debut on Netflix. It focuses on the young Elisabeth Amalia Eugenia of Wittelsbach, born Duchess of Bavaria, who, thanks to her love for Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary, finds herself catapulted into the Hapsburg court and, in order to find her place and make her voice heard, must juggle power intrigues, wars and international relations, political crises and her perfidious mother-in-law Sophia. Thus, in an atmosphere reminiscent of The Crown, we see Sissi's expectations collide with the reality of a struggling empire that stifles all individuality.

At the centre of Corsage, presented in the Un Certain Regard section of the Cannes Film Festival, instead of the innocent little girl brought up in the country gentry who finds herself almost empress by chance, there is a woman in her forties, introverted and intolerant of court life, who prefers voluntary confinement and nature to palace glamour. The film, inspired by My Heart Is Made of Stone: The Dark Side of the Empress Elisabeth written by Michaela Lindinger, portrays a free and restless spirit, a woman full of character who cultivates an ambiguous relationship with her cousin Ludwig of Bavaria, is a heavy smoker, has an addiction to opium, spends hours reading poetry and studying Greek and is obsessed with her own weight and beauty fading with age. This is the portrait that, while reminiscent of a sort of Lady Diana ante-litteram, comes closest to the real Elisabeth.

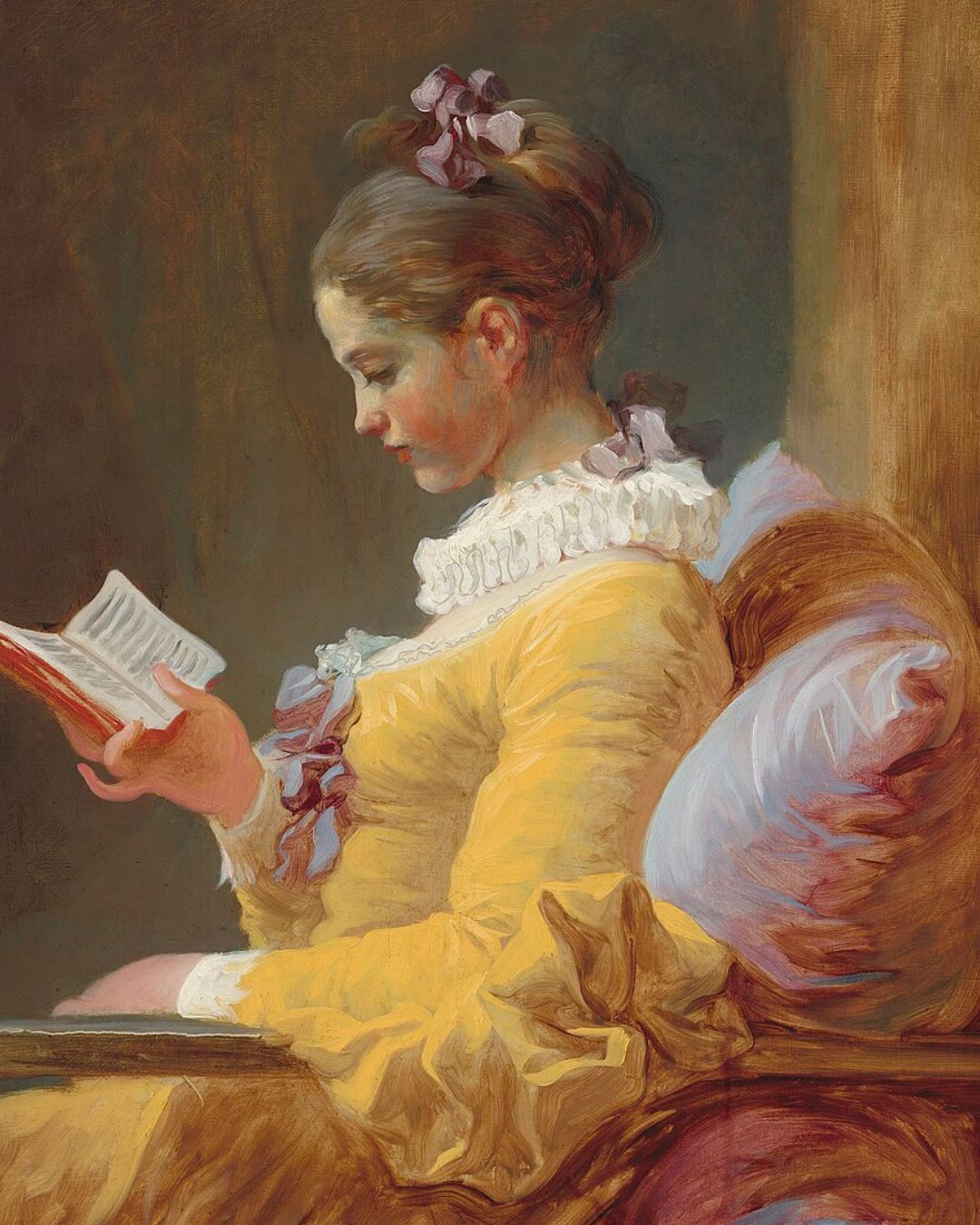

"She smoked, took cocaine, and in a Greek harbour tavern had the image of an anchor tattooed on her shoulder." As the sources document, Sissi was a modern woman. For better and for worse. Every detail that has emerged about her has helped create a complex myth of her, far from being as glossy as the 1950s films she starred in. She had a passion for travel, sport, horse riding and the poetry of Heinrich Heine, but she also had several addictions, especially to cocaine and alcohol. As well as a real obsession with physical appearance. His beauty routine was as renowned as it was bizarre. She underwent diets, fasting, long walks and physical activity sessions in an almost manic manner to the extent that she maintained a fifty-centimeter pelvis for the rest of her life. Apparently, the court pharmacist was instructed to prepare a moisturizing body cream made of almond oil, rose water, white wax and whale fat especially for her, which she alternated with masks with raw meat and strawberry puree and baths in hot olive oil. The greatest attention was, however, devoted to her very long hair, which she let herself brush for hours ('when I comb my hair I let my mind wander elsewhere' she used to say) and washed every 20 days with a mixture of cognac and eggs. A very elegant woman, as we see in Winterhalter's portraits, Sissi loved to impress and, together with her hairdresser Fanny Angerer, she loved to gather her hair into plaits and illuminate it with star-shaped diamond clasps, which matched perfectly with the cascade of tiaras, bracelets, necklaces and rings she used to wear. Beauty and youth were a kind of slavery for her, so much so that she stopped having her portrait taken after 30 years and, after the suicide of her beloved son Rudolf, allowed herself to fall into the depression from which she had suffered all her life, moving further and further away from courtly glamour until she was murdered by the Italian anarchist Luigi Lucheni on 10 September 1898.