What are Stonewall Riots? From drag community role, street culture and LGBTQIA+ manifestations to the birth of Pride

Every year in June we celebrate Pride, a time of celebration, vindication, community, but also and above all struggle, in memory of Stonewall. The Stonewall riots - or uprising - began on the night of 27-28 June 1969, when police raided a gay club between 51 and 53 Christopher Street, New York, the Stonewall Inn. Patrons of the bar, residents of the neighbourhood and the street community rebelled against the officers' harassment, triggering six days of protests and confrontations in the surrounding streets. It was neither the first nor the last instance of confrontation between the LGBTQIA+ community (who at the time had no idea of such an acronym) and the police, but Stonewall was immediately charged with all the symbolic force necessary to define it as one of the major turning points of the gay liberation movement.

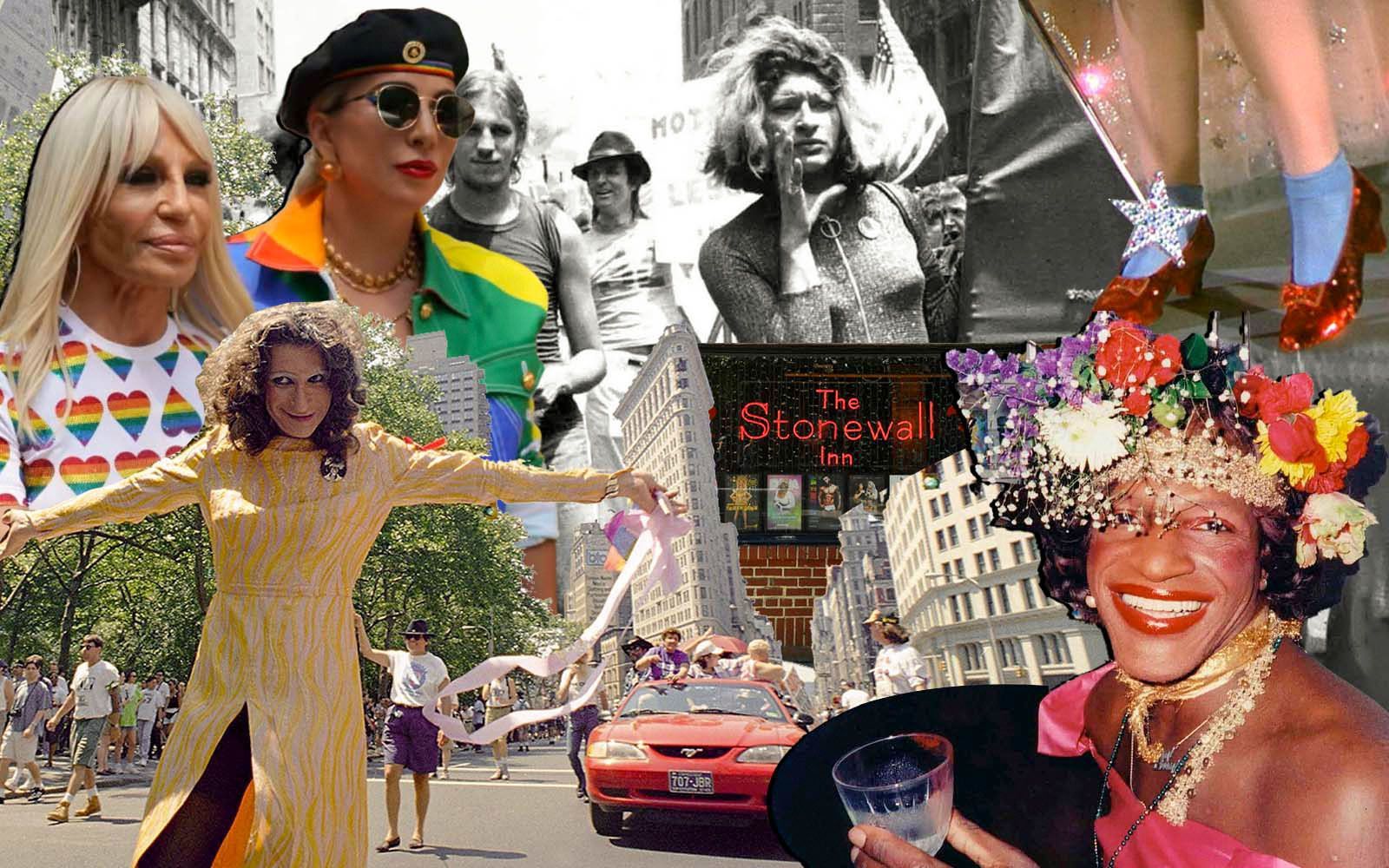

Between myths, legends and idealisations, we retrace the starting context, the United States of the 1960s, and the main reference figures who led to these events, such as Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera.

The context: alcohol, raids, mafia and homophobia

In the early 1960s, in view of the World's Fair to be held in 1964, New York City Mayor Robert Wagner Jr. initiated a campaign to 'clean up the city', i.e. to remove gay bars, particularly in the neighbourhoods of Greenwich and Harlem. Two of the most significant interventions were the revocation of alcohol licences from all bars and the continuous raids (which sometimes even took the form of real undercover operations) of the police on gay bars. In those years, in the United States, it was forbidden to wear more than three garments of the opposite gender to one's own, under penalty of lagalera for 'impersonation', holding hands, kissing or dancing in a 'non-heterosexual dynamic' was still illegal, and in general, the DSM (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) considered homosexuality to be a sexual deviance, an antisocial personality disorder - for which homosexual people underwent 'therapies' such as electroshock or lobotomy.

In this prohibitive context, with strong social pressure and zero public representation, LGBTQ+ people could only express themselves and socialise in those 'places of refuge', such as bars and clubs; the only places where they could meet other people, network and live with a little more serenity. The Stonewall Inn was one of them.

Like most of the clubs in the Village, the Stonewall Inn was in the hands of the Genovese, a Mafia family who had bought it for $3,500 and, from a straight restaurant and nightclub, had turned it into a gay bar, the only one in Greenwich where people danced. It was registered as a bottle bar, private, so it did not have a liquor licence, as each customer would have to bring their own bottle. Many bars run by the Genovese family managed to get by without licences, this was because the family had managed to bribe the NYPD's 6th Precinct. Those who ran establishments like the Stonewall Inn were somewhat the last wheel on the bandwagon, because it was places like this that allowed the mob to really cut costs; for example, there was no fire exit, or we can remember that glasses could not be washed because there was no running water near the bar.

At the same time, however, it was considered Greenwich's gay bar, something of an institution, not least because it welcomed the drag scene. And it is important to point out that, in those days, the category 'drag queen' also included transgender, transsexual women and non-binary people. At the Stonewall Inn you could find 98% gay men, a few lesbian women and several homeless teenagers. There was a nice mix of age, tending to be in their thirties, and ethnicity, including whites, blacks and Latinos. To enter, moreover, there was an unwritten rule that you had to unequivocally present yourself as gay, which created quite a few problems when there were raids.

The Stonewall riot: the night of 27-28 June 1969

The corrupt cops usually informed the bars run by the Mafia families before the raids took place, allowing alcohol and other illegal activities to be concealed. On the night of 27-28 June 1969, police arrived at the Stonewall Inn unannounced, arresting 13 people, including employees and customers who violated the state's gender-appropriate dress code.

Suddenly an officer hit Stormé DeLarverie on the head as he forced her into the van to take her to the station. Here history is mixed with myth, and it would appear that Stormé shouted "Why don't you do something?", inciting the crowd to throw what was lying around at the police. Legend also has it that there was a memorial service that night for Judy Garland (considered a gay icon), who had passed away a few days earlier, on 22 June, and that people were angered by the interruption of such a 'sacred' moment. Others claim that the riots started because Marsha P. Johnson threw a brick, other versions because Sylvia Rivera threw a heeled shoe. In any case Stonewall was the first active response against the violence perpetrated by the police and society of the period.

Within minutes hundreds of people began to riot, throwing coins, bottles, pebbles and various objects at the officers (two of whom were injured). The police, some arrested people and a journalist from the Village Voice barricaded themselves in the bar, so the crowd tried to set the place on fire. The fire brigade and reinforcements from the Tactical Patrol Force, a riot squad known for its brutality, arrived, whereupon the people present chanted various chants, such as 'We are the Stonewall girls, We wear our hair in curls, We don't wear underwear, We show off our pubic hair', a humour not entirely appreciated by the TPF, who pulled out their truncheons. After the night, the clashes continued the following days, for almost a week, bringing thousands of people from feminist and Black Power activist groups to the New Left. The protests gradually turned into sit-ins, meetings, lectures, articles and testimonies, and from there the New York GLF, or Gay Liberation Front, took shape, with the goal of gaining the rights to openly live one's gender, sexual orientation and expression beyond conformity, without fear of arrest.

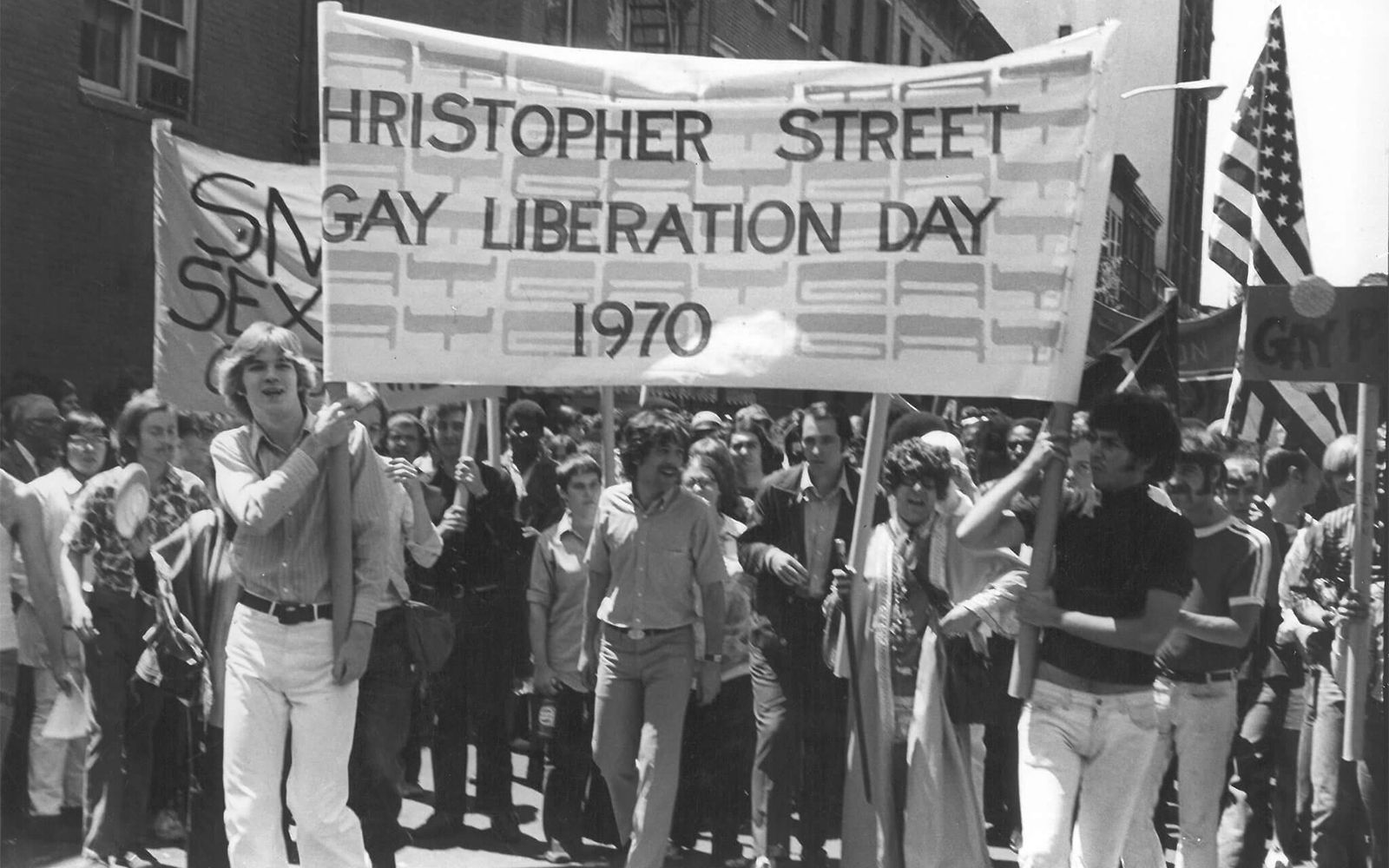

On 28 June 1970, one year after Stonewall, the first Pride was celebrated, where thousands marched through the streets of Manhattan from the Stonewall Inn to Central Park on what was then called 'Christopher Street Liberation Day'.

28 June 1970, the first Pride in New York

The role of marginality: black trans women sex workers

The Stonewall Riots are part of the history of the LGBTQIA+ movement, but they have often been mythologised by online narratives, which have spectacularised the events, partly out of adherence to the camp culture common to the entire queer community, and partly because as Eleonora Santamaria writes in Drag there is "this tendency to want to make "sparkling" and "colourful" in memory even those events of the LGBTQ+ minorities that were anything but carnivalesque. Not that there weren't ironic provocations and freedom of expression, but those riots weren't a cabaret show, it was also a bloodstained reality'. At Stonewall itself there were no deaths, but one cannot obscure the violence and yes, even the deaths, of those years.

At the same time one must keep in mind that queer history starts from the street, from the edge, from the margins of society, from minorities. This is a point that also allows us to understand why Roland Emmerich's film released a few years ago, Stonewall (2015), received a lot of criticism, since it chose to present as its protagonist a white cis-man who for most of the film narrates the difficulty of confronting his sexuality - a choice made "to reach a wider audience of people, because it is easier for heterosexual people to understand and empathise with the story."

The story of Stonewall, in fact, cannot ignore the role played by figures such as Stormé DeLarverie, a lesbian butch drag king and activist, Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera. The latter is often associated with the mythical throwing of the first brick at Stonewall, but both only took part in the riot later in the night. The term 'trans' was not widely used at the time, so Marsha and Sylvia were considered drag queens, sex workers, activists for trans people and homeless people. The P between Marsha's first and last name was there because when people questioned her gender, she sarcastically replied Pay it no mind.

Lesbians and trans women, black, were some of the key people involved in the act of resistance, mainly because of the community atmosphere they were able to create in those difficult places of extreme poverty, marginalisation and danger. Marsha and Sylvia were landmarks of the community, founders also of STAR, the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries group - one of the first houses, a refuge for all people who had been thrown out of their homes, or who had suffered violence, coming out of prison, and so on. Their contribution was often forgotten, or deliberately ignored - like when they tried to stop Sylvia from speaking at Pride in 1973.

The Stonewall Inn wasn't the first LGBTQIA+ riot in the United States: there were the riots at Cooper Donuts bar in Los Angeles in May 1959, and then in 1966 the Compton's Cafeteria riots in San Francisco's Tenderloin neighbourhood. Both are events that have been little recounted and little investigated, their exact dates are not even known; of Los Angeles, the only record is in John Rechy's book City of Night, the events in San Francisco, however, are recounted in Susan Stryker's 2005 documentary, Screaming Queens.

Stonewall, on the other hand, marked the beginning of gay activism, partly because it took place in a broader context of civil rights movements. It was recounted early on, and because of this it settled into collective memory, within and outside the queer community, until in 2016 President Obama designated the venue, its streets, pavements and surrounding park - Christopher Park - the first national monument in recognition of the place's contribution and significance to LGBTQIA+ rights.